The reel people

|

|

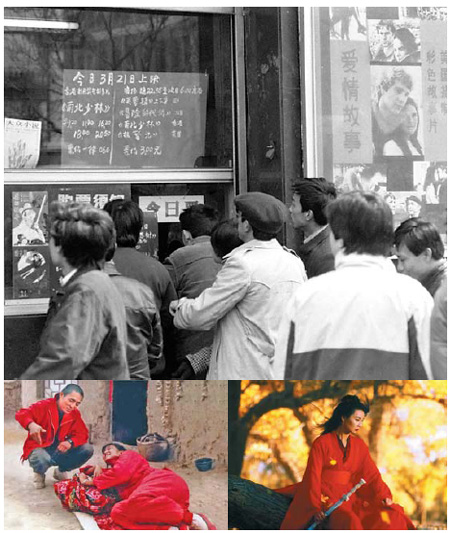

Top: American film Love Story is shown at the Dahua Film Theater in Beijing on March 21, 1988. Above left: Zhang Yimou explains the plot to Gong Li while shooting Red Sorghum in 1987. Above right: Maggie Cheung stars in Hero directed by Zhang Yimou in 2002. Top: Tang Shizeng / Xinhua; Above: photos Provided to China Daily |

After the chaotic "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), during which more than 300 Chinese movies were banned, filmmakers could not wait for a new era to begin. Taboo films were screened again and audiences flocked to movie theaters with great passion. In 1979, more than 29 billion cinema tickets were sold and one of the nation's most popular magazines, Popular Cinema, had a monthly circulation of more than 9 million.

Three years after the nation's reform and opening-up, a group of filmmakers, critics and experts set up China's most important film awards. The 1981 event was named the Golden Rooster Awards because roosters were seen as diligent creatures that rose early to wake people up for work.

The first big winner was veteran director Xie Jin. His Legend of Tianyun Mountain won four Golden Roosters for the best director, film, cinematography and production design.

Legend was part of Xie's "reflection trilogy", focusing on political campaigns, such as the "cultural revolution", that imposed suffering on ordinary people. The most famous movie among them was Hibiscus Town (1986), a tragic love story starring Jiang Wen and Liu Xiaoqing. The film raked in more than 100 million yuan ($15.6 million), a staggering amount considering a cinema ticket cost only about 0.2 yuan.

Xie, who died in 2008, was the first Chinese director to become a member of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences and worked in the industry for 60 years.

When Hibiscus Town was sweeping across China, Zhang Yimou, a graduate from Beijing Film Academy, was worrying about the growth of the sorghum plant in a small village in Shandong province.

Before entering film school he had spent 10 years as a farm laborer and factory worker during the "cultural revolution" because of his family background. When he applied to the film school, he was 27, and over the regulation age for admission. Thanks to his outstanding photography talent he was accepted into the academy when it first opened in 1978 after the "cultural revolution".

In 1988, Red Sorghum wowed Berlin International Film Festival judges, winning the festival's top award, the Golden Bear. It was the first time a Chinese film had earned such a top honor at an elite international film festival.

The film was bursting with ravishing colors and was a hymn to the power of life, elements that would become Zhang's trademark in his later, award-winning films.

He won the Silver Lion at the Venice International Film Festival with Raise the Red Lantern in 1991 and the Golden Lion in the following year with The Story of Qiu Ju.

In 1994, his epic, To Live, about an ordinary couple's tribulations over decades of rapid changes in New China, earned the Grand Jury Prize in Cannes. In 1999, he won Venice's Golden Lion award again with Not One Less, a story about a 13-year substitute teacher and her students.

Although some critics accused Zhang of pandering to Western judges by only revealing the negative parts of Chinese society, his narrative techniques and visual style have won him international acclaim.

However, as Zhang's global glory rose, China's local film market declined.

In the 1990s, going to the cinema was no longer the top choice for entertainment as more households turned to television and young people discovered karaoke and discotheques.

In 1998, four years after China set the annual quota of 10 foreign films in theaters, Titanic raked in the highest box office revenue in China that year. Academic Dai Jinhua compares the local film industry in the late 1990s with the ill-fated ship. In 1999, China's box office sales had fallen to 800 million yuan from 2.4 billion yuan in 1991.

The industry pushed for urgent reform. In 2002, the year after China joined the World Trade Organization, a regulation allowed more private and foreign capital in a domestic film production, distribution and screening. Previously, production was largely controlled by State-owned enterprises.

The new laws allowed local private companies to produce and distribute films independently and set up their own theaters. Foreign companies could also cooperate with local partners to produce films and build cinemas.

In 2002, Zhang Yimou produced the first Chinese blockbuster: a big-budget period drama with abundant kungfu sequences and star-studded casts. Hero received mixed reviews but amazing box office revenue of 250 million yuan, compared to Titanic's earnings of 360 million yuan four years previously.

Some thought Zhang had given up his pursuit for artistic breakthroughs but focused only on the box office, while others believed he had explored a new path for the revival of local productions.

The controversial Hero did bring people back to cinemas; so did a number of films that followed its pattern, such as Feng Xiaogang's The Banquet and Chen Kaige's The Promise.

Although many people panned these films, many more went to see them.

Director Jia Zhangke, Zhang's younger alumnus of the Beijing Film Academy, challenged him in public. The 36-year-old had won the top honor at the Venice Film Festival in 2006, the year Zhang released his third costume kungfu blockbuster Curse of the Golden Flower.

Jia insisted on releasing his Golden-Lion-winning Still Life, an art-house film about people who left their homes under water for the building of the Three Gorges Dam, on the same day with Curse.

Zhang did not comment, but his producer told Jia to shut up and think more about how to attract a bigger audience. The war ended with Curse raking in 300 million yuan while Still Life took in only 2 million yuan.

Meanwhile, a new generation of filmmakers took another direction.

In 2006, former music video director Ning Hao made black comedy Crazy Stone. The 5-million-yuan film, about the hustle and bustle caused by a precious stone, earned 20 million yuan. It was energetic, fresh and hilarious. Both audiences and critics liked it because it was not too removed from real life, nor was it as highbrow as some art films.

"I never underestimate viewers' IQs," Ning says. "If I make a film that performs very well at the box office but audiences feel they have been duped, I wouldn't be happy at all. I'd feel better if it was the other way around."

Since 2003, China's box office has seen an average annual growth of 35 percent and reached a record 10 billion yuan in 2010. Few film markets in the world have grown as fast.

But there are still the problems of piracy, lack of creativity and the competition from Hollywood films - just to list a few.

Yet what happened over the past three decades has proven that the Chinese audience, like those anywhere else in the world, respond to a good story.