Flying Tigers still roar

Updated: 2011-11-02 14:48

By Sun Ye (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Veteran World War II flyers gather from around the US in New York's Chinatown to mark the 68th anniversary of the Flying Tigers' deactivation. Photos Courtesy of MOCA |

|

|

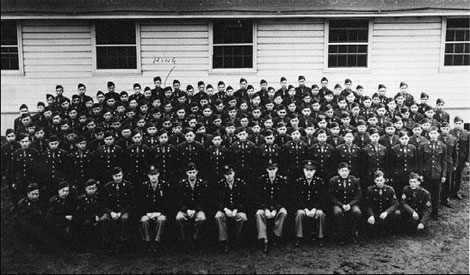

The 407th Air Service Squadron Group, better known as the Flying Tigers, in a 1943 photo. |

While the heroic World War II air squad's members are aging, their legacy isn't. Sun Ye reports.

James B. Wong remembers many of the planes that landed looked like colanders from all of the bullet holes.

It scared the teenager.

"You're afraid," he says.

"You're afraid you may die. Then, you feel sorry for those who come back shaking. And you feel sorry for those who didn't come back."

It was World War II that brought the Taishan, Shandong province native back to his homeland, after he had circumvented the Chinese Exclusion Act as a "paper son", claiming to be the child of a US citizen, to start a new life in Stuyvesant, New York.

He was drafted into the 407th Air Service Squadron Group - better known as the "Flying Tigers" - at age 15. "They asked me, 'Do you want to go to China and fight the Japanese?'" he recalls.

"I said, 'Of course. I don't want to go to Europe'."

Wong believed it wise to enter General Clair Chennault's Air Service Group and avoid the carnage roiling Europe.

After a year of training in mechanics, electronics, hydraulics and radio-message center operations, the 250-member Flying Tigers squad was sent to the China, Burma and India (CBI) theater of war.

Wong was one of 20,000 Chinese-American soldiers recruited from among the 120,000 Chinese living in the US in 1940, according to Veteran Administration figures.

It was about two years before the Chinese Exclusion Act - for which the US apologized this summer, when congress passed the Resolution of Regret- was repealed.

The media was starting to declare, "The Chinese are our friends!" as the two countries became allies in the fight against Japan. Before that, the Chinese-Americans crammed into China towns were considered "coolies" and "piglets" - a far cry from today's stereotype of Asian-Americans as educated and wealthy.

The status shift is even more dramatic for Wong and his ilk, as the Flying Tigers are internationally celebrated for their heroism.

The members represent "the best and the brightest" of the Chinese-American community, historian Christina Lim says.

Lim organized a meeting and panel discussion for which the veterans flew from around the country to New York's Chinatown on September to mark the 68th anniversary of the group's deactivation.

Wong seized the occasion to visit the Museum of Chinese in America in New York, where he saw a photo of him with 20 other army mechanics in Patterson Field, Ohio, in 1943.

When he exclaimed, "I was there!" the other visiting octogenarians - most with wheelchairs and hearing aids - crowded in to look.

While Wong hoped to fight in the CBI theater, Flying Tiger Ed Len instead sought a more dangerous post in Europe.

"As a young man, you just want to be part of it," says Len, who was 19.

His dispatch to China, despite his request, was the Stratford, Connecticut, native's first visit to his ancestral homeland.

Len says he had never seen another Chinese family before arriving in the Far East in January 1944, after almost three months on ships, cattle trains and planes.

"For me, entering wartime China was a big adventure," Len recalls.

He was shocked to see the privations of China then.

"Barefoot, starved Chinese carried woks on their backs so they could cook when they had food," he recalls.

"I was there to help. I didn't care if they were poor."

Most of the Flying Tigers were stationed in Chongqing, where the Nationalists' central government and Chennault's air force headquarters were located.

Wong was dispatched to Xi'an, Shaanxi province, where his Cantonese and Taishan dialect proved useless. The only means for the bombsite mechanic to communicate with local people was through writing.

"The main thing is they trusted us," Wong says.

"Although they didn't speak our language, they knew we were there to help."

The US troops developed a good rapport with the community.

"They even offered to buy supplies for us, and tried hard to talk to us," Wong recalls.

He now speaks passable Mandarin, most of which he learned during his time in northwestern China.

The 407th Air Service Squadron Group never saw direct combat but, rather, was responsible for groundwork and technical support. Sometimes, there was so much work they had to toil through the night.

But they returned to the US unscathed to start new lives through the support of GI bills.

Most returned to school. Some enrolled in elite universities such as Stanford, Cal-Berkeley, New York University and the University of Southern California.

They bought homes and settled down across the country.

Wong had brought his new wife back to the US through the 1945 War Bride Act.

He wore his uniform when he attended university in Maryland, where he earned a degree in agriculture. "I told the department director that I wanted to go back to China to teach them to use chemical fertilizers," he says.

He also published the novel Jade Tiger after spending three years researching his air squad.

"I think people need to learn more about the group," he says.

He went on to get a double PhD in chemistry from the University of Illinois. He started his own Sino-US import-export business after stints with Rexall and Kraft. His company has boomed in the past decade.

Some squad members became famous, including journalist William Hoy and Saturday Night Live producer Ed Len.

While their American lives took diverse turns after the war, the bonds forged during combat in China remain.

Since their first casual post-war get-together in 1956, the reunions have transformed into grand galas that include wives and later-generation family members.

They recently returned to China and marveled at the country's modernization.

Wong, for one, believes his times with the Flying Tigers were propelled by "fate".

"It changed my whole life," he says.