Removing the thorn from her heart

Updated: 2011-11-11 13:16

By Yang Guang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

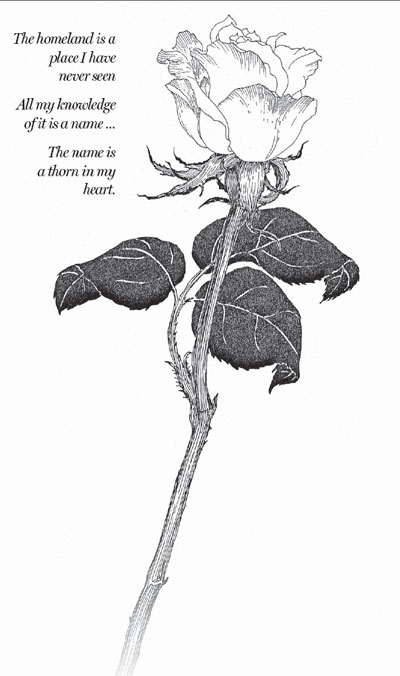

A sketch by Hsi, who is also a trained painter. |

Much of Taiwan poet Hsi Mu-jung's work is about the loss and rediscovery of her homeland. Yang Guang reports.

It was 1949, and the ship was about to sail from the mainland to Hong Kong. Hsi Mu-jung, 5, was given a gold ring and a black cotton-padded coat with her name sewn on the inside by her mother. All of her siblings were given the same, and they compared their rings to see whose was bigger. "Only years later, did we learn from mother that we were given the rings and coats in case we got lost on the journey," the 67-year-old Taiwan poet recalls at the launch of her latest anthology, In the Name of Poetry, in Beijing.

"The coats were to identify us, and the rings were financial assistance to help bring us up," she explains, tears welling in her eyes.

Hsi was born in Chongqing to a Mongolian family. They moved to Hong Kong in 1949 and to Taiwan five years later.

A trained painter, she began to compose poems at 13. Her first poetry anthology - mostly love poems - was published in 1981. It became an instant success both in Taiwan and on the mainland.

"Writing poems was spontaneous for me," Hsi says. "In that turbulent age, I was always adapting to new classes and it was difficult to become accepted. I started writing poems in my diary to ease my loneliness and frustration."

She went to college in Belgium in the 1960s and returned to teach painting at a college in Hsinchu.

"The homeland is a place I have never seen/ All my knowledge of it is a name / The name is a thorn in my heart."

She wrote these lines in 1979 but was not able to set foot on the mainland until 10 years later, when restrictions relaxed.

In 1989, she went to the Inner Mongolia autonomous region for the first time and has since visited the Mongolian Plateau several times a year.

"On the plateau, I do nothing but walk," Hsi says. "The sweet grass is broken by my steps and its fragrance permeates the air. Grasshoppers jump around and eagles hover in the sky, while I just walk, thinking of nothing."

Two essay collections, Mongolian Lessons and In Pursuit of My Homeland, were published in 2009 to record her explorations of Inner Mongolia's land and culture.

"Since my first visit to the Plateau in 1989, the idea of making nomadic culture known to more people has smoldered and grown into a fire," she says.

"By constantly walking and writing, I was finally able to find my homeland in my heart and in my poems."

In the Name of Poetry is her seventh poetry anthology and includes about 50 pieces, mostly written after 2005. Three of them, each about 200 lines, retell Mongolian heroic narrative poems, drawn from stories in the Mongolian epic Jangar.

Jangar is one of the world's three mega-epics, together with Kyrgyzstan's Manas and the Tibet autonomous region's Gesar. It deals with King Jangar's battle with the evil Mongolian warlord Mangus, a threat to Mongolia.

"The Chinese translation of Jangar was the first book I obtained when I returned to the Mongolian Plateau," she says. "Stories in Jangar and The Secret History of the Mongols have been a constant temptation to write about."

Hsi says her greatest regret is she can't speak Mongolian. Before 5, she talked with family members in Mongolian, but she gradually forgot how to speak the language as she moved around. She started taking Mongolian lessons, on and off, several years ago and can now spell her name in Mongolian.

On her website, she writes regularly to a fictional Inner Mongolian boy, about her observations of their national culture. She has finished 10 letters, and a collection will be published when there are 21.