Handwriting, Best in China

Updated: 2011-11-28 15:15

(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

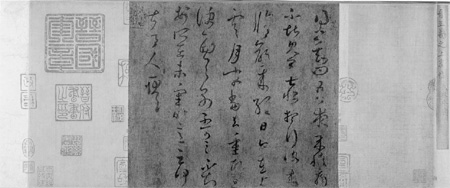

The Tang Dynasty copy of Wang Xizhi's Shangyu Tie, preserved at the Shanghai Museum. Provided to China Daily |

Wang Xizhi (王羲之) is known as the "Sage of Calligraphy" in China and Asia, although none of his original works have survived the ravages of time and dynasties. Little wonder, since the master calligraphist died 1,650 years ago. He had lived from 303 to 361, during the Jin era (AD 265-420), directly after the tumultuous Three Kingdoms period (AD 220-280).

His most famous and currently most reproduced work is Lanting Xu (兰亭序), originally a foreword that Wang wrote for a collection of poems published by his friends. That, too, only survives in reproductions.

At the Shanghai Museum, there is another rare copy of his calligraphy, the Shangyu Tie (上虞帖).

This was originally a letter Wang had written in reply to a friend and has seven lines of only 58 characters. In it, Wang apologizes for not meeting his friend because of an upset stomach, and follows up with a few comments on family and friends.

The writing is smooth and fluent and the characters are executed with grace, showing off the calligraphist's mature style in his later years, according to Shan Guolin, director of the Chinese calligraphy and painting department at Shanghai Museum.

During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), a team of experts went through all the confiscated antiques and artwork. One of them, Wang Yuren, found the scroll and immediately recognized it as a masterpiece. The museum staff evaluated it as a fake, but Wang stood his ground and insisted on keeping the scroll at the museum.

Three years later, another expert Xie Zhiliu recognized it as a very precious copy, but could not decide its specific age. The museum then borrowed an x-ray scanner, and it was determined that the scroll came from the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

"The calligraphy of Wang Xizhi and his son Wang Xianzhi (王献之) played an important role in the evolution of Chinese calligraphy," says Chen Xiejun, director of Shanghai Museum. "His writing turned Chinese characters into a smoother beautiful style, which was an important historic transition."

It was during the Jin era that saw Chinese calligraphy slowly change from the formal Lishu style to the more aesthetic Kaishu style - which has become the standard style for Chinese characters still in use today.

"The copy is very close to the original, and very true to it. When the original is no longer available, a true copy is considered next best, and a national treasure," Chen says.

Last year, an antique copy of Wang Xizhi's cursive hand scroll, Ping'an Tie (平安帖), was sold for a record 308 million yuan ($46 million). The complete copy has nine lines, but was torn into two. The piece that was auctioned was 24.5cm long and 13.8cm wide and had only four lines of calligraphy.

Wang's fame as a master of Chinese calligraphy grew during and after the Tang Dynasty. It was said that the first Tang emperor admired Wang's work so much that the original of Wang's most acclaimed work Lanting Yu was buried in his mausoleum.

Legend has it that Wang Xizhi once came across a poor old woman who was distressed because she could not sell her bucket full of paper fans. Wang wrote some characters on the fans and told her to sell them. The illiterate old woman doubted his words, and reluctantly took the fans to market. To her surprise, she sold off all the fans at very high prices.

Another tale has it that Wang developed his fluid writing style through looking at his pet geese, and that he found inspiration watching their necks and how they moved.

Wang Xizhi had seven children, and the youngest of them, Wang Xianzhi, is the most famous calligrapher after him. Today, they are often referred to as the "Two Wang masters of calligraphy".

The Shanghai Museum's antique calligraphy collection is housed on the third floor, arranged in chronological order so visitors can follow the evolution of Chinese calligraphy through the ages.