Paper trail to prosperity

Updated: 2012-01-11 10:19

By Cheng Yinqi and Guo Anfei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

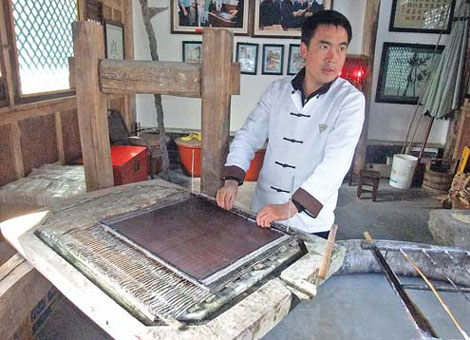

A Xinzhuang villager makes paper by traditional methods at home. Photos by Cheng Yingqi / China Daily |

|

|

Long Demao was the first Xinzhuang villager to reveal to outsiders local papermaking secrets. |

Ancient methods of papermaking offer better livelihoods to villagers in Yunnan province. Cheng Yinqi and Guo Anfei report.

People in Yunnan province's remote Xinzhuang village used to hate Long Demao. Now, they love him. They had believed the 36-year-old sold out their history when he moved out of the village in 2006 and revealed to outsiders the local papermaking secrets handed down since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

"On the day I left home, people pointed fingers in my face and called me 'the bastard who sold out his ancestors'," Long recalls.

"But I believed I had better insight than any of them. Now, I've proven it - they admire me instead of despising me. It's not that I'm the best papermaker. But I opened my mind to the outside world earlier than others."

The Tengchong county government couldn't find anyone in Xinzhuang village to showcase the papermaking process to tourists in the village's neighboring town, Heshun, when Tengchong decided to develop a tourist district in the old town in 2006. Developers had spent an entire day scouring Xinzhuang for someone to showcase the process but to no avail - that is, until they met Long.

"I took the opportunity," Long says.

"It's a struggle to survive, to earn more money and to live a better life. Some believed I was just giving away the secret we've kept from strangers for centuries."

So, Long moved to Heshun - two hours from Xinzhuang by bus - and has demonstrated the process and sold paper to visitors for five years.

Long has since become one of the village's richest people. He sells the paper in Heshun for four times what he could in Xinzhuang. He has even hired several villagers to help him.

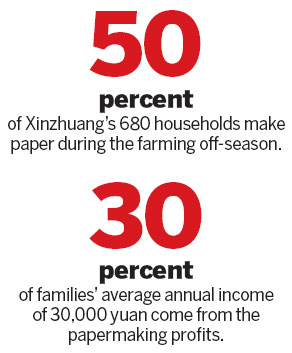

More than half of Xinzhuang's 680 households make paper during the farming off-season. The profits account for 30 percent of families' average annual incomes of 30,000 yuan ($4,763).

Their paper is sought after because it's believed to contain fewer harmful chemicals. Tea plantations in the province often purchase it to package their pu'er tea.

"The market was so good from 2005 to 2007 that it outpaced our production capacity," says 64-year-old Xinzhuang native Long Zhanxian, who is also director of the village's new papermaking museum.

The pu'er tea market flourished in Yunnan and Guangdong provinces starting in 2002. It swept the country and peaked between 2005 and 2007, when production outstripped demand and prices plummeted.

"Actually, the tea market's decline didn't destroy the papermaking industry, because our paper has other uses, such as making the paper money burnt for traditional funerals," villager Long Zhanliu says.

The 33-year-old has made paper for 20 years.

Long Zhanliu, with his wife and two sons, produce 30,000 sheets a month. These sell for 0.35 yuan a sheet and provide about 90 percent of the family's income. "If your paper is good, you don't have to worry about sales, anyway," Long Zhanliu says.

Small plant owners go door-to-door in Xinzhuang almost weekly. The paper is usually made in sheets that are 68-cm-by-73-cm - a size suitable for tea packaging and funerary money. Villagers make different sizes for custom orders.

"I work without a break from 7:30 am to 11 pm," Long Zhanliu says.

"It doesn't require much physical strength to make paper, but you still must be strong, because it keeps you busy every minute. The income isn't necessarily better than that from working in cities. But we can at least take care of our children at home."

While few villagers realized papermaking's potential, one Beijinger did.

Editor Long Wen discovered Xinzhuang while traveling among 72 villages in the Gaoligong Mountains while researching local intangible cultural heritage.

"When I first visited, the villagers didn't take any pride in their papermaking skills," the 35-year-old recalls.

"They admired the modern papermaking industry and yearned for urban lives. That's horrible for the protection of ancient skills."

Long Wen helped Xinzhuang establish a handmade paper association in the following three years. But the association didn't run well because it had neither funding nor a fixed location.

That's when Long Wen came up with the idea of opening a museum, which was designed and built with help from his friends Hua Li and Wang Yan from Beijing.

Wang explains why he invested in the museum: "I believe the paper will find a place among high-end business users. It's original. It's historic. It's fancy. All we need is a standard to evaluate different households' production."

Wang hopes they can develop a system to measure the paper's quality and that they can find buyers of paper of different quality levels.

"What we want to do is promote the cultural value of the paper through commercial activities," Wang says.

"If we earn profits, the benefits will go to the museum and village. We'd like to promote the museum. Consequently, more people will know about the village's culture. Selling paper isn't our ultimate goal."

But Long Demao, the man who works in Heshun's tourism zone, is considering opening a paper plant in his hometown.

He has learned a similar handmade paper had been produced for centuries in some villages in Yunnan's Dali city, before some businesspeople invested in and monopolized the paper's sales.

"The investors control all orders," Long Demao says.

"You can't sell your own paper without their permission. I don't want this to happen to my village," he continues.

"If investors open a factory and ensure any villager who wants to make paper can get a job there, and that the plant pays everybody's social insurance, that would be great. I'd even consider working for them."

Deputy village chief Wu Jiaqiang says he has also heard about the monopolies around Dali.

"That won't happen to us, because our village's paper association has already applied for the patent for the villagers," Wu says.

"So, even if other people learn our papermaking methods, we're still the exclusive users of the skill passed down by our ancestors."