Waste not, want not

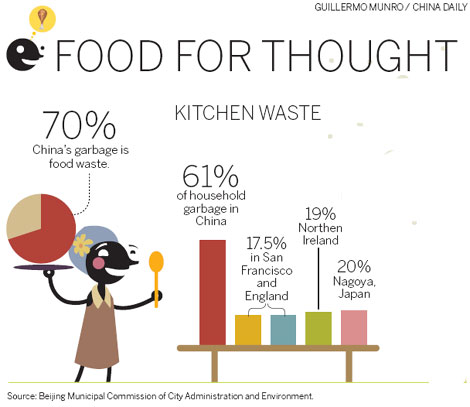

Food waste comprises roughly 70 percent of the country's garbage and is difficult to collect, process and recycle - and hazardous not to. Zheng Xin, Wang Kaihao and Cheng Anqi report.

While you often hear Chinese parents tell their kids to not waste food, the fact is food waste accounts for about 70 percent of the country's mounting garbage production. That's compared to less than 20 percent in many developed countries, where sorting and processing have been the norm since the 1980s. And as China's waste processing capabilities simply can't keep pace with the amount of garbage that is being produced, food waste is a bigger problem than it might be. "As people's lives improve, the catering industry is booming and dietary habits are changing, so we're producing massive amounts of food waste," Beijing Technology and Business University's Department of Environmental Science and Engineering professor Ren Lianhai says.

"China has a long way to go in terms of better disposal because it lacks a national policy, scientific management and processing methods."

Beijing was among a slew of local governments to pass regulations in 2011 about trash sorting and food waste disposal, largely because of public concerns about "gutter oil" - cooking oil retrieved from drains and sometimes reused by restaurants.

The problem is that governments, NGOs and enterprises are struggling to cook up solutions for kitchen waste disposal and are finding they don't work or are difficult to implement.

Recipes that are being tried include composting the waste into organic fertilizer using enzymes and earthworms, burning it to create electricity, feeding it to pigs and even using gutter oil as biofuel to power Dutch Airlines' planes.

"Kitchen waste has become a primary pollution source and imposes serious risks to people's health and the environment," Ren says.

Ren, who has studied waste management for more than a decade, explains the dangers of burying kitchen waste in landfills.

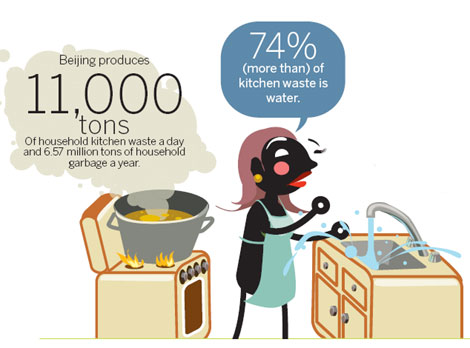

China's food waste is 74 percent water - that's three times the saturation of US and European kitchen waste. It's referred to as "wet waste" globally.

The pressure of being buried, combined with the chemical reactions of microbial biodegradation, causes the water to ferment and percolate, forcing hazardous and even carcinogenic sludge to ooze out, Ren explains.

And food waste poses sanitation hazards before it even reaches the landfills, he adds.

Take Beijing, for example. The capital's households produce 11,000 tons of kitchen waste, plus the 2,500 tons that spew out of restaurants, a day. But the municipality's three large-scale processing plants can only handle 800 tons a day of food waste.

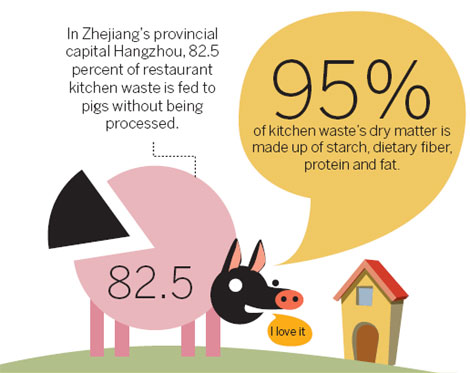

The most common methods of kitchen waste disposal are feeding it to pigs and composting.

While the evidence is inconclusive, many experts worry that turning household kitchen waste into pig slop is dangerous.

Pork is China's most popular meat and its presence in hog feed creates the risk of homology. Homology is cannibalism among animals that typically don't eat the meat of their own species in nature and can cause prion infections, such as mad cow disease.

The Ministry of Agriculture has created a panel to study the risks but hasn't reached a consensus.

Although the practice is common in Japan and South Korea, some of China's local governments, such as Fujian province's Xiamen city, have outlawed it.

Organic composting, though promising, also faces challenges.

Many pilot projects have problems, such as people not sorting their trash, or collectors dumping sorted trash together or waiting too long to pick it up, creating a stench.

"Trash processing is a chain," Beijing Municipal Commission of City Administration and Environment garbage disposal official Chen Ling says.

"We can't expect people to sort out kitchen waste if there's no channel to handle it."

Ren says the chain's weak links come from a diffusion of responsibility.

"The dilemma is that experts complain about management, while officials complain about technological deficiencies," he says.

There are also chemical reasons it's difficult to compost in China.

"Chinese food contains too much oil, especially animal tallow, which coats the waste in a thick cover that seals out oxygen microbes need to biodegrade the waste," Ren explains.

One solution is to dilute the food waste with other biodegradable trash, such as paper.

Insufficient storage is another problem. Farming is seasonal, but food waste is produced year-round.

And even if there were more storage facilities, compost rots too quickly to last from harvest until the next planting.

In addition, the saltiness of Chinese food means the fertilizer it becomes can make arable land fallow over time, Ren says.

Still, several projects are running that turn kitchen waste into organic fertilizer around the country.

Many NGOs, such as the Fujian Environmental Protection Volunteer Association, exchange organic vegetables for correctly sorted trash.

The produce is grown with the organic fertilizer from their community's waste, meaning that, theoretically, the melon rind a household throws out can end up back on the family's table as a fresh organic melon.

The association's founder Zheng Dijian believes it's all about incentives.

"If people get something out of sorting their garbage, they will," he says. "If they don't, they won't."

Another kitchen waste use idea being tried out is incineration to create electricity.

Trash in Chaoyang district's Chaoyang Circular Economy Industrial Zone, in Beijing, is compressed to wring out the water, left to dry for five days and then incinerated at the 200-hectare solid waste incineration plant.

About 1,600 tons feed the furnaces a day, creating 220 million kilowatt hours - equivalent to 70,000 tons of coal - annually. About 70 percent of that electricity powers the industrial zone while the rest flows into the North China Power System.

But it's uncertain how - and if - this could work on a nationwide scale.

Ren, who works on a national panel devoted to developing the country's kitchen waste disposal system, says Beijing's government plans to build at least one large wet waste processing plant in every district and county.

The problem is that nobody's sure what sort of plant they should construct.

The same quandary faces the proposed 100-150 plants to be built nationwide before 2016. They should be able to process a total of up to 30 million tons a year.

"I'm glad to see people are working on this," Ren says.

"But we still have a long way to go."

Erik Nilsson contributed to the story.