She did it her way

Updated: 2012-02-09 13:41

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Subhead: Controversial choreographer Jin Xing returns in triumph to New York, the city that gave her “a voice”. Kelly Chung Dawson reports.

Related reading: Time for change

When Chinese choreographer Jin Xing presented a dance retrospective titled Shanghai Tango at New York City's Joyce Theater recently, she fulfilled a promise she made to herself 20 years ago as a young dance student studying in Manhattan.

"When I left New York in 1991, I told myself I would only come back to New York with my own dance company," Jin said at a question-and-answer session following one of the weekend performances. "I kept this promise in mind for two decades and God, I did it!"

|

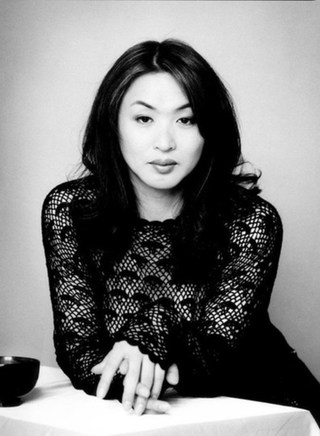

| Jin Xing |

Shanghai Tango includes 10 works that Jin has choreographed over a three-decade career. The choreographer is famed for a dance style that is graceful and imaginative, but also for her remarkable back-story.

At 9 years old, Jin enlisted in the Chinese army to study dance, and later went on to win the "China’s Best Dancer" award at 17. She went to New York in 1987 through a fellowship program organized by the Chinese government in collaboration with the Rockefeller Center, and studied with dance legends Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham and Jose Limon, among others.

Audiences at Joyce Theater laughed appreciatively as she described getting to know the Chelsea neighborhood “upside and down.” When a moderator mentioned the theater had waited a long time for Jin to perform there, she said with a smirk: "Good things come later, right?"

"I feel really proud of myself," Jin said in an interview with China Daily. "I reached my goal and kept that promise. I care about the audience's response more than I care about critics, and the audiences here in New York have been very warm and communicative, and very appreciative of my work."

Her return to New York is significant not only for the fulfillment of the promise she made to herself -- it is also noteworthy for being her debut in America as a woman.

It was not until 1995 that Jin underwent gender reconstruction surgery, but in her words: "The surgery was simply a life step that needed to happen. I had to go through it, but ultimately it was not the only step in my life."

Jin now lives in Shanghai with her husband and three adopted children.

Her time in New York was instrumental in shaping the course of a controversial career as China's most prominent modern dance choreographer, and the founder of the country's first independent dance company.

"Coming to New York was like my eyes were suddenly opened wide," she said. "In China, I wasn't asked to express personal feelings in my work. So, when I learned modern dance and was suddenly asked to speak in my own voice, it was really tough. That hadn't been part of my education."

She recounted telling one choreographer that a dance assignment was "nothing".

"'It has no jumps, no turns, it doesn’t show off my technique,' I told him. And he said, 'Jin Xing, you don't need any more technique. You have enough technique for the next life. What you need is style.' From that day forward, it changed my entire idea of dance. I try to carry that idea forward today in educating students at my own school in Shanghai.

"Living in New York (at the corner of 15th Street and Seventh Avenue), she made friends with many Americans. One teacher advised her not to spend too much time with other Chinese people.

"Speak English and spend time with Americans," the teacher told her. "If you want to speak Chinese, go back to China."

She recalled dancing at the same theater in which she performed recently, as an ensemble dancer in other people's programs, adding she watched other people dance while sitting in the same seats that fill the theater today.

New York is the same and yet "so much cleaner," she said with a laugh.

Jin's work is filled with references to the Asian aesthetic, with traditional Chinese costumes and fans.

"I never thought about putting labels on my work as an Asian choreographer," she said.

"It's all from instinct. The fact that I use black and red in some pieces, those are simply colors that stick out for me from childhood memories. I remember red flags and banners, and everyone around me wore black. It's not my intention to be political, or for there to be a message in my work.

She referred to Island, a work in which two nearly nude men dance intimately.

"People ask if I choreographed this piece for the homosexual community, and the answer is, no. I don't represent any group of people. Gender issues are not something I think about. I feel I communicate honestly through my work, and people either understand or they don't understand. It doesn’t matter."

Her inspiration comes from life experience, she said. "It's usually just a story I want to tell." One piece came about after the end of a three-month relationship, another was based on a famous Chinese theater drama titled Thunderstorm, in which a woman struggles with illicit feelings for her stepson.

Red Wine is about modern Chinese women who fall into the trap of wanting expensive shoes, alcohol and an assortment of lovers. Another piece attempts to capture the lives of rural Chinese women hundreds of years ago. The dancers appear to bicker, gossip and tend to their households — all without standing on their feet.

"I can see my personal growth over time. The simplicity in some of my earlier works reads to me like a diary of my life as a choreographer. Some of these pieces I've been dancing to for 20 years. I'm 44 now, so sometimes I need extra time to warm up — and yet my dancers say I perform the pieces slightly differently every single night.

"Too many choreographers work to please other dancers, she said. "I choreograph for the general public. I don't think you should ever leave the public behind."

She has never looked up to any other choreographer, she said.

"I have respect for artists worldwide, but I don't admire anyone over anyone else. Everyone is the same. What another artist has I will never have, and what I have they will never have. We should simply appreciate each other for what we can create and what we are."

As for American audiences, Jin believes that they know very little about China.

"But American attitudes are changing. I think it's a positive thing. Life takes turns, and everyone has their time. Now is China's time. Anyway, if Chinese culture and dance was the same as American dance, how boring would that be? It all makes things a little more interesting."