Meet a rock star games designer

|

|

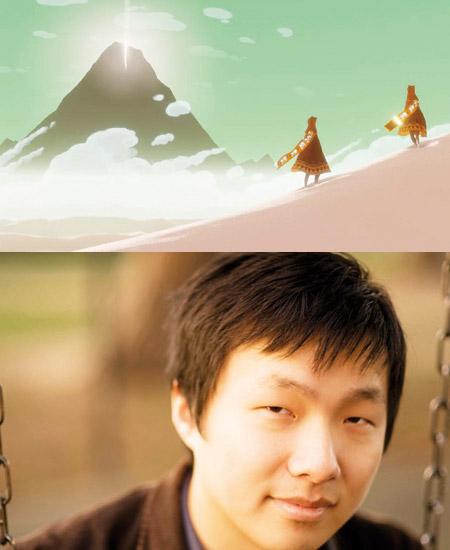

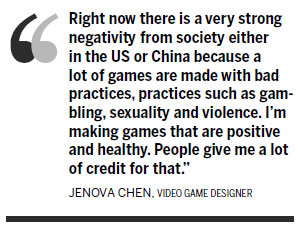

Above: Video game designer Jenova Chen has his design philosophy - making games that are positive and healthy. Top: Chen's latest online game, Journey, was recently released on PlayStation network. Photos Provided to China Daily |

His autograph is the most widely sought by young Chinese gamers at conventions, and aspiring games developers look to him as an inspiration. Eric Jou finds out what makes Jenova Chen tick.

He is dressed in a light blue button-down shirt and simple jeans. The only thing that betrays his calling is a PlayStation game controller belt buckle on his waist.

Jenova Chen, 30, is treated like a rock star in the Chinese video game developer world. He's looked upon as a shining example of success in an industry where developers are mostly faceless names on the end credits.

"I think the reason that I have a lot of fans isn't because of my games but because of what I represent - an average Chinese guy from an average family who could actually make a game that is played by the entire world," Chen says.

"I think I represent a possibility. If I wasn't Chinese, most Chinese people probably wouldn't know me."

Chen is celebrated in the country also because he has developed his own philosophy on game making that sets him apart from the competition.

He doesn't make violent fighting games with loosely garbed women or bloody team shooters that reward players for headshots. Instead, Chen's games fall under another category, almost on its own.

"I'm not making another Farmville game or another dungeon crawler game. I'm actually making something that is positive from the social standard," he says. "Right now there is a very strong negativity from society either in the US or China because a lot of games are made with bad practices, practices such as gambling, sexuality and violence. I'm making games that are positive and healthy. People give me a lot of credit for that."

Chen's games are said to be more experiential than what is found on the market today, eliciting emotion through how players interact with the world. His most famous game to date, Flower, is perhaps the best example of his design philosophy.

In Flower, the player takes the role of the wind collecting flower petals from point to point, all the while bringing color and life to a city of gray. While Flower has levels and goals, the ultimate aim of the game is to create a positive response and reaction from the player through the interaction, Chen says.

"If your goal is to create a unique emotion like Flower, for example, or a peaceful feeling of spreading love or nature, if you apply a typical game's interaction through challenges, they tend to get very frustrated because they fail or too excited if they succeed. These are very aggressive feelings," he says.

"So when you create new emotions through interactivity in games, interactive design becomes the frontier where you can push the boundary."

Born and raised in Shanghai as Chen Xinghan, Chen grew up with a background in computers. His father worked in the computer software industry and had hoped Chen would follow in his footsteps. Chen says that at around third grade, he was enrolled in a computer programming class against his will.

"I didn't want to go. I really loved drawing. All my teachers told my parents I should go to art school. But my dad thought that in China it's all about guanxi, or connections - who your parents know - and because he was in the software business, he thought I should study computers."

Chen says he was rebellious at first and shuddered at the thought of going to computer classes. But over time, he discovered something alluring - video games. After finding out computers could play video games, Chen says, he went to class early every week "just to play the games".

As he got older, Chen's gaming world expanded and he was introduced to Nintendo's home console, the Famicom. Because consoles and console games were more expensive, he gravitated toward PC games.

It wasn't until Chen got into high school that he would gain his peculiar English name, Jenova.

Chen recalls being enamored with SquareSoft's (now Square Enix) epic role-playing game Final Fantasy VII. Both Chen and a close classmate were so captivated that they decided to name themselves after characters from the game.

His friend chose Cloud, the main protagonist of the game, and Chen thought it would be more "bad ass" to be Jenova.

Chen didn't really start making games until he went to university. Despite majoring in computer science, and winning multiple medals and competitions in the field, he decided to take courses outside of his major. Going back to his childhood passions, Chen enrolled in various art related courses, such as photography and digital art.

Not having anyone watch or direct him, Chen says he went "rogue", sneaking in to take all the art school courses he could. In the process, he managed to complete a second major for digital arts and design.

"I'm kind of a traitor to computer sciences. I spent 10 years programming, but as soon as I had autonomy, I switched back to art."

Chen next enrolled for a master's program in fine arts at the University of Southern California. It was at USC that Chen's gaming vision took off. At first, he wanted to use his background in digital arts to work on CG films and, perhaps one day, work for Pixar.

However, USC transferred him to the then new interactive media department because of his software programming background.

The school paid for Chen and some of his classmates to head to San Francisco for the Game Developers Conference 2004. At GDC, Chen saw student-developed games, many of which were amateurish. GDC opened up a world of possibilities, and gave Chen his confidence and propelled his vision.

Back at USC, Chen and his classmates went on to develop Dyadin (2005). They submitted the game to the Independent Games Festival and the game caught the attention of big-time game publisher Electronic Arts.

Chen and his team next started working on Cloud, a game based on his childhood affliction with asthma in Shanghai.

He was about to graduate and in order to stay in the US he needed to land a job fast, so he and his partner started pitching their game.

"We pitched to pretty much every single possible publisher on the North American continent, and Sony and Nintendo were the only two companies crazy enough to actually want to do business with two students who hadn't graduated," Chen says.

"We picked Sony because it was close, in LA. Nintendo liked us and they wanted us to move up north to Seattle but it was too far from home."

Chen's deal with Sony turned out to be a double-edged three-game exclusive deal. Chen would get his name out there and his games were made. But, unfortunately, he would be tied to Sony's PlayStation brand, ultimately limiting the number of people he could reach.

Chen's claim to fame in China was also due to his partnership with Sony.

Due to the limited access to home consoles in China, many people were unable to purchase a PlayStation 3. The PSP, on the other hand, was very popular in China, and one of Chen's games, Flow, was available for the PSP.

In Flow, the player's goal is to guide small multi-segmented centipede-like creatures across the screen to consume small organisms that appear on the screen. But unlike conventional games, it has no menus or guidelines.

Chen's latest game, Journey, has just been released on PlayStation.

It received glowing reviews from critics and game websites, such as Kotaku.com. Journey will also be Chen's first online game. Flow, Cloud and Flower have all been single-player games. To Chen, Journey is a very big separation from the norm, and he says he wanted to make an online game that brings people together.

"I wanted to create something that can create an emotional bond between two players, rather than say how 'I can kill this person or how can I beat him'," he says. "When you see a player, it'll be like walking in the forest alone and being glad to see someone walking next to you."

For Chen, the possibilities are just beginning.