For zoos, choices on life and death

|

|

Zoos must decide which species are most crucial to save. Lion-tailed macaques, left, will no longer be bred at the St. Louis Zoo, which also has American burying beetles and Humboldt penguins. Photographs by Todd Heisler / The New York Times |

Conservation efforts are forcing bitter decisions on which species will be saved.

St. Louis, Missouri

As the number of species at risk of extinction soars, zoos are increasingly being called upon to rescue and sustain animals, and not just for marquee breeds like pandas and rhinos but also for all manner of mammals, frogs, birds and insects.

To conserve animals effectively, however, zoo officials have concluded that they must winnow species in their care and devote more resources to a chosen few. The result is that zookeepers, typically animal lovers, are increasingly being pressed into making cold calculations about which animals are the most crucial to save.

If there are criticisms, they are that zoos are not transforming their mission quickly enough from entertainment to conservation. "We as a society have to decide if it is going to be ethically and morally appropriate to simply display animals for entertainment purposes," said Dr. Steven L. Monfort, the director of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, part of the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. "In my opinion, that model is broken. There needs to be an explicit role for zoos to champion species."

Dr. Monfort wants zoos to raise more money for the conservation of animals in the wild and to make that effort as important as their captive collections. Zoos, he said, should build facilities - not necessarily open to the public - that are large enough to handle whole herds of animals so that more natural reproductive behavior can occur. And less emphasis should be placed on animals that are popular attractions but are doing fine in the wild, like African elephants and California sea lions, Dr. Monfort said, adding that they should be replaced with animals in desperate need of rescuing.

Many zoo directors say that such a radical reordering is not called for and that each zoo does valuable work even if conserving just a few species.

In their first century, American zoos plucked exotic animals from the wild and exploited them mainly for entertainment value, throwing in some wildlife education. When wilderness began disappearing, causing animals to fail at an accelerating pace, zoo officials became rescuers and protectors. Since the 1980s, zoos have developed coordinated breeding programs that have brought dozens of animals, like the golden lion tamarin of Brazil, back from the brink.

The increasingly difficult challenge is to be a force for conservation while continuing to put on a show. Sea lions are doing fine in the wild, but the St. Louis Zoo decided to spend $18 million on a new pool that will be filtered and ozonated for clarity. Why? Because sea lions are very popular and their home was decrepit.

"We are always balancing the public experiencing with conservation needs," said Jeffrey P. Bonner, the chief executive of the zoo. "If you ask me why I have camels, I would say that we need something interesting for people to see at the back of the zoo in winter, and they are always outside."

As standards for animal care rise and zoos install larger, more natural-looking exhibits, there is room for fewer animals. In the 1970s, the primate house in St. Louis held 36 species of monkeys and apes. Now it has 13.

Zoos also have come to understand that for animals to reproduce for the long term without inbreeding, they need to maintain much wider gene pools. There are 64 polar bears in captivity in American zoos, far short of the 200 considered optimal for maintaining the population over 100 years.

So zoos have been adding to the numbers of some species while culling others. St. Louis says it houses 400 more animals but 65 fewer species or subspecies than it did in 2002.

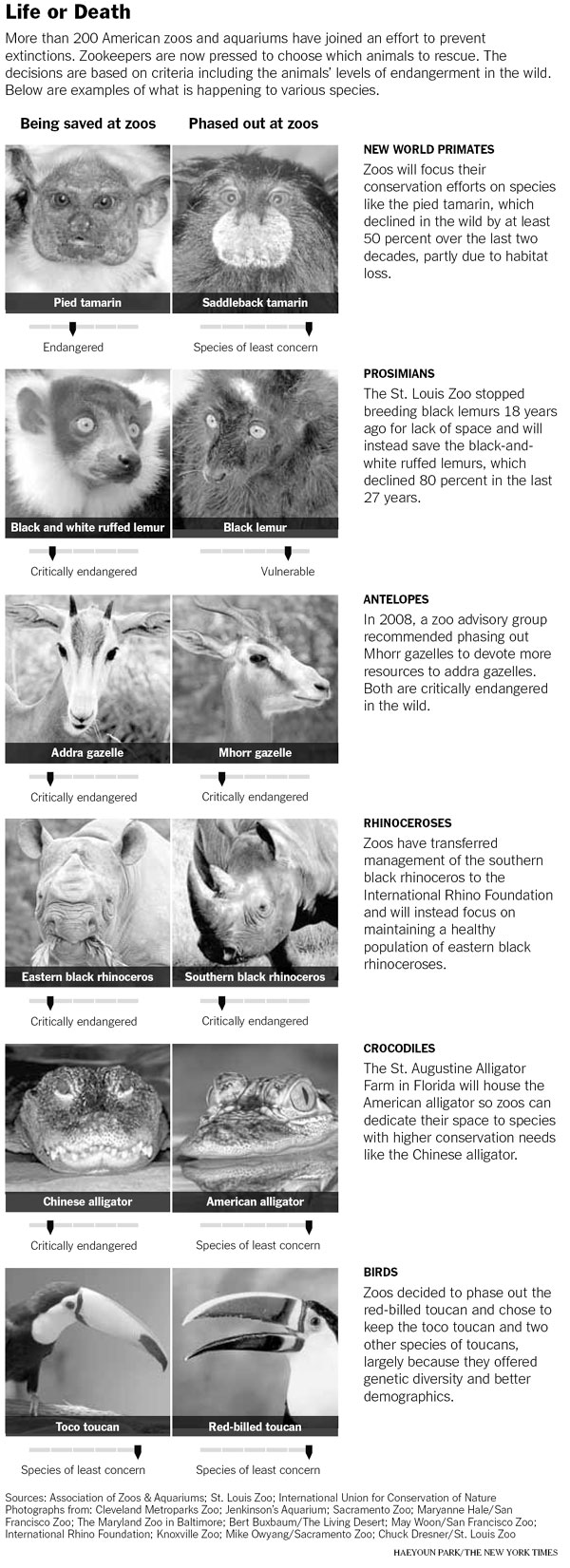

As conservation pressures mounted in the 1990s, the Association of Zoos & Aquariums, which oversees zoos in the United States, began putting together advisory groups of zookeepers that look across entire families of species and advise on which ones should be made priorities and which ones should be phased out. Criteria include uniqueness, level of endangerment, importance of the animal's ecological role, and whether there is an adequate population in captivity for breeding. The International Union for Conservation of Nature estimates that nearly one-fourth of mammals are at risk of becoming extinct in the next three generations. The situation is even more dire for amphibians and seabirds.

At the St. Louis Zoo, several buckets of dirt now house the threatened American burying beetle, so named because it buries the corpses of small animals and lays its eggs around them.

Once, the beetles, with their brilliant red markings, ranged over 35 states. By the time the United States Fish and Wildlife Service listed them as endangered in 1989, there was one known population left, in Rhode Island. At the government's behest, the St. Louis Zoo, in conjunction with a zoo in Rhode Island, has been breeding them and returning them to the wild.

Bob Merz, the zoo's manager for invertebrates, says the effort was worthwhile because the beetle might play an irreplaceable role in the ecological web. He considers picking species worth saving akin to life-or-death gambling. "It is like looking out the window of an airplane and seeing the rivets in the wing," he said. "You can probably lose a few, but you don't know how many, and you really don't want to find out."

The New York Times