Burn warrior

|

|

Veteran doctor Chai Jiake operates on a burn victim at Beijing's No 1 Hospital affiliated with the People's Liberation Army General Hospital. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

|

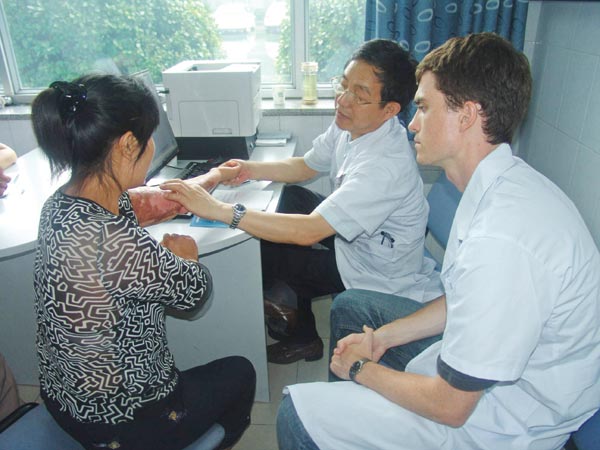

Chai Jiake treats an outpatient at the hospital's clinic. |

Calm in the face of horrifying injuries, a champion of emergency medicine builds a stable of doctors who share his passion, Liu Xiangrui reports.

While most people feel uncomfortable with the pain and the stink of burn wounds, Chai Jiake has to endure them daily.

Related: Doctor puts his heart into hypertension discoveries

Chai even puts his nose close to the burns, when he makes rounds through wards packed with patients in gauze bandages. The 60-year-old veteran doctor can judge the wounds' healing stage or degree of infection, just by smell.

Widely acknowledged as an internationally leading burn expert, Chai works at Beijing's No 1 Hospital affiliated with the People's Liberation Army General Hospital. He has treated more than 10,000 burn victims in his career, with a remarkable total cure rate of 99.8 percent.

However, being a top burn doctor is much more challenging than the figures suggest, he admits.

Chai is frequently sought for important medical tasks by the nation or the military. In recent years, he has participated in rescues at more than 50 major accident scenes, from asphalt and gunpowder explosions to bus combustion accidents.

In 2006, Chai faced a huge emergency when 35 armed policemen were critically injured while fighting a great forest fire in Heilongjiang province.

Taking two flights to get from Shandong, where he was having a conference, to Heilongjiang and spending 18 restless hours on the road, Chai buried himself in work despite the weariness.

"Three men were in critical condition, and 13 others had serious inhalation injuries and faced danger of suffocation," Chai recalls.

He worked through the night to finish 17 urgent tracheotomies and finally got the patients' conditions under control. Then he had to make a bold decision: to transfer all the injured because the facilities at the site were so poor.

"It was the first time we transfer so many critically injured patients. Any accidents on the way could threaten their lives," Chai says, recalling the pressure of making that move. He made sure measures to ensure the victims' safe passage were worked out down to the smallest details.

Chai's team worked nonstop and finished 21 skin-grafting operations in the next three days. They overcame numerous difficulties, including saving one soldier three times from setbacks that put him on the verge of death.

For 80 days, they made the hospital their home - eating and sleeping there. To Chai's pride, they ultimately realized their goal of "early recovery, low disability and zero death" despite the extreme injuries, the number of patients who needed critical care and the physical toll long hours of surgeries took on the medical team.

Chai himself got an eye inflammation and lost 4 kilograms of weight during the period. Immersed in the crucial rescue work, Chai wasn't able to meet his 83-year-old mother, who happened to be visiting Beijing from her rural home, for more than 20 days.

When Chai's wife arranged a brief visit by his mother to his hospital, they had a box lunch together in the ward.

"I felt so sorry when my mother showed up before me with a crutch and looked at me with tender eyes," Chai says, in his green military uniform.

"He is a filial son," says Chai's wife Liu Jixiu. "But he'd always take patients before anything else."

Chai was determined to become a doctor since childhood, when he was inspired by a story of how a doctor saved the lives of both a woman and her child during an abnormal childbirth in his village in Shandong province.

He became a "barefoot" doctor - a doctor with basic medical training to offer preliminary services in the village - after graduating from high school. He left home at 20 and joined the military as an assistant nurse.

Chai later got recommended to study at a military medical university, where he chose his current field after learning that deaths from burns ranked second among all deaths from accidents, only after traffic accidents.

He learned from Sheng Zhiyong, one of the founders of China's burn medicine, before heading to the New York University for post-doctoral study in the 1990s.

He accepted the invitation from his current hospital and returned in 1997.

Back then, his department was small with 37 ward beds.

With Chai's help, many of his students gradually became new-generation burn experts, and the department has also expanded quickly. Now, it has several hundred doctors and 250 beds, with about 4,000 inpatients every year. Its growing fame has attracted large crowds of patients, including foreigners.

According to Wang Shujun, a nurse who has worked with Chai for years, Chai has paid attention to a special group - the numerous rural residents attracted to his place.

Wang remembers one farmer patient and his family hurried to Chai's office. Wang, knowing Chai had a busy day and was having a nap, tried to stop them at the door.

But Chai, who knew their identities by their accent, quickly invited them in and diagnosed them.

"They might want to go home as soon as possible if the problem is not so serious," Chai explains.

"Staying one more night in the capital will give them extra burden financially. We doctors should give patients timely help, not extra burdens."

Chai has collected more than 100,000 yuan ($15,900) for patients from poor families through donations.

He believes that saving patients' lives isn't the end of his job. He proposed the plastic aesthetic approach of burn therapy, which has inspired him to many medical research achievements.

"Some burn victims bear eternal scars deep in their hearts, not only on their bodies," Chai says. "We must try our best to improve their life quality and help them reconnect with society after such traumas."

Chai's former patient Zhang Zhichao, 57, was seriously hurt in a terrible fire in 1998. Saved from the brink of death, with many tendons in his fingers seriously damaged, Zhang was desperate to see and feel his toes and fingers as the bandages were peeled away.

Zhang recalls that, on the gloomiest days, Chai often stayed for hours to comfort him, patiently explaining his conditions and discussing his recovery plans.

"After the operations, I have kept practicing calligraphy all these years like he encouraged me to. I've recovered part of my hand's functions," Zhang recalls, showing the pieces he has recently drawn and written.

"He is not only a master doctor," Zhang says of Chai, "but also a good psychiatrist."

Chai is determined to build his department into an international-level burn medical team. "The power of one man is limited. But I'm willing to lay a foundation for the young."

Contact the writer at liuxiangrui@chinadaily.com.cn.