Chinese scholar and his work in French

This April, 69-year-old Li Zhi-qing received a letter from the French ambassador to China. Sylvie Bermann warmly praising Li's promotion of the French language and French literature.

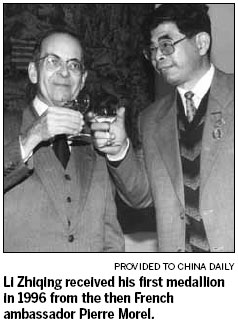

She also told Li that he will soon be awarded the Commander Medallion of the Order of Academic Palms. It's the highest level of the third-grade order of Chivalry of France for academics and others who have made major contributions to French national education and culture.

This is Li's third medallion after receiving the lower-level knight and officer medals.

"It's a great honor for me; the more exciting part is being recognized for doing my favorite thing," Li says.

Li was the born in an intellectual family in Shanghai. His father was a chemist who once studied in the US.

Li says his lifetime passion of French was originally inspired by Fu Lei (1908-1966), the renowned Chinese writer and French-language translator.

In childhood, Li recalls, his parents' house was always crowded with Shanghai's intellectuals and scholars, and Fu was often one of them.

To taste the original flavor of French literature, he entered the Shanghai International Studies University's French department in 1962.

"French education was not well-developed in China until 1964, when China and France established the diplomatic relations," Li says.

Then came the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), and for more than a decade, he worked at a farm and then a factory.

But Li kept on reading to keep his hand in. His French skills survived thanks to reading the French version of Selected Works of Chairman Mao Zedong.

In 1978 Li met the then Party secretary of Shandong University, Sun Hanqing, who invited Li to teach at the school and help with its nascent French education. Ever since then, Li has been an evangelist for the French language.

In 1979, Li finally had a fleeting glimpse of France after studying French for 17 years. His first visit was only a short stay in Paris, a stopover on a business trip to Africa.

"I was like a bumpkin with all my money sewn up in my suit pocket," Li chuckles.

In the following years Li lobbied Shandong University to launch its own French department. In 1994 his dream came true.

There were only a few French workers in Shandong province that constructed an electricity-generating station in Zouxian county, Li recalls. He hosted a French club in one classroom of his campus and invited these French workers to meet with students once every two weeks.

The French workers screened some French movies that were not commonly found in China at that time, and then discussed the films. They also brought French books.

Soon after, a French elevator manufacturer came to the provincial capital Jinan and provided internship opportunities to Li's students. Li also helped 10 of his students to study in France with the support of Rotary International and Lions Clubs International, two worldwide service-club organizations.

In 2000 Li helped the Ocean University of Qingdao (now the Ocean University of China) to establish a French department. That year there were 22 French-major freshmen.

Fang Liwei, one of that first batch and now the deputy director of the French department, says the strict teacher would list at least 50 books for the newbies. Li also required them to read French newspapers such as Le Monde and Le Figaro every week.

Meanwhile Li participated in writing several textbooks, and initiated the founding of the Qingdao branch of the French Alliance. He also campaigned to make Qingdao a sister city of Nantes and Brest.

Today he hardly seems retired. He comes to school regularly, and flies frequently between China and France.

"I wish I could die during teaching, just like an actor dying on stage," says Li. "To me it's the biggest happiness."

Hu Qing in Qingdao contributed to the story.