Printed bones

Peking University Third Hospital has recently announced that its new 3-D printed orthopedic implants have produced good results in clinical trials.

Using a printer to produce medical implants, body parts and living organs may sound like science fiction, but it is not.

Scientists in a few countries, such as the United States, have used 3-D printing, a process of laying down successive layers of material in different shapes to make a three-dimensional solid object, according to a digital model.

|

|

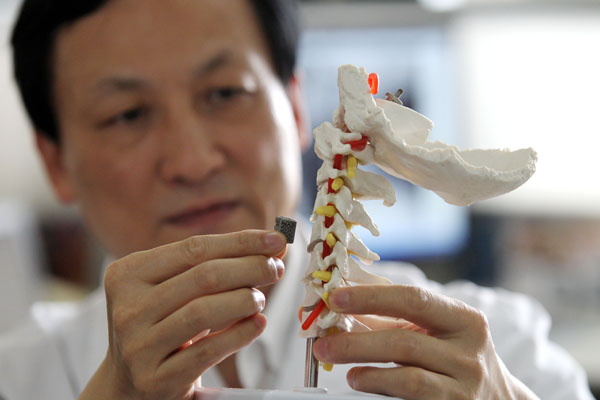

A 3-D printed medical implant is displayed at Peking University Third Hospital in Beijing. More than 50 patients have used dozens of such implants.PHOTOS BY ZHU XINGXIN / CHINA DAILY |

The 3-D objects are used in three ways: for surgery simulation, to produce lifesaving medical implants and artificial body parts, and to create living tissues and organs for drug testing.

In China, Peking University Third Hospital recently announced its orthopedics department had produced a new type of orthopedic implants using a 3-D printer. The implants have produced good results during clinical trials.

"We started the clinical trial to test those implants last year, and all the patients participating in the trial are recovering well," says Liu Zhongjun, director with the department.

Cooperating with a Beijing medical device company that owns an imported 3-D printer, the hospital has produced dozens of hip replacements and artificial vertebral bodies. To date, more than 50 volunteer patients have tried the implants.

The test is the first time that 3-D printed artificial vertebral bodies are used in human bodies in the medical world, although artificial vertebral bodies have been used in orthopedic surgeries for years, Liu says.

The material is nothing new. The hospital uses titanium powder to print, a special metal that has been applied to make body implants for decades.

But the shapes of the 3-D products are very different from traditional ones, in a positive sense, Liu says.

Orthopedic implants are widely used for patients suffering from bone damage caused by injuries or diseases. They are inserted into joints and bones to restore normal functions, such as spine implants to help anchor the spine.

But because of the limits of traditional manufacturing methods, the shapes of orthopedic implants are usually geometric patterns, and as a result, they cannot attach to bones firmly without additional cement, screws and fixing plates.

The 3-D printing, instead, is able to print titanium powder into any shapes, as long as the computer that controls the printer has a digital model to follow.

"In another word, the 3-D printed orthopedic implants can match better with bones around them than traditional ones," Liu explains.

Besides, the tiny pores of the new implants, another feature of the 3-D device, enable bones to grow into the implants, Liu adds.

Liu’s team launched the program in 2009. The hospital provided designing know-how, and the medical device company digitalized the design.

In mid-2010, they started trials on sheep, and in 2012, the team got permission from health authorities for human trials.

A woman surnamed Huang, became the first patient for the clinical trial.

The 54-year-old Beijing resident had suffered from severe dizziness and stiffness in limbs caused by cervical spondylosis, a degenerative condition of the cervical spine.

|

|

The 3-D printed artificial vertebral bodies are used in human bodies for the first time in the world. |

In September 2012, Huang heard about 3-D printing, and decided to use the new 3-D printed artificial vertebral bodies.

"I see it as a good opportunity to experience new technology," she says.

Within a few days after the surgery, Huang’s symptoms disappeared. Her quarterly checks have shown positive recovery results.

Lyu Chao, 32, is the latest patient to benefit from the technology.

Before his surgery in July, his fingers, knees and lower legs often felt numb, and he could not walk or run fast.

Lyu is the 20th volunteer. The hospital plans to have at least 22 volunteers before they apply to health authorities for clinical use, according to Liu Zhongjun, director of the clinical trial program.

Liu says, "Producing medical devices through 3-D printing saves time and materials, and thus the cost will be lower than traditional methods."

It also has the potential to custom-print medical implants, and create living organs for transplants, Liu adds.

Qi Xiangdong, a senior cosmetic surgeon with General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command, says Chinese hospitals have been trying to make use of 3-D printing since 2002.

Many have applied the technology to create lifelike organ models so that doctors can simulate surgery procedures and pre-plan for complicated surgeries to enhance safety and efficiency, says Qi, who’s a member of the standing committee of Digital Medicine Association under the Chinese Medical Association.

In 2008, doctors in Qi’s hospital successfully made a 3-D printing digital model for the upper part of a cervical vertebra, and hospitals in Shanghai have been using 3-D printing to help design cosmetic implants for several years, Qi says.

But to make models for surgery simulation and preparation is different from creating living tissues and organs.

"It is great that more Chinese hospitals manage to develop 3-D technology-related medical solutions for patients," Qi says. "With the technology, doctors can provide better treatment to patients."