Nobel prize winner's connections with China

|

|

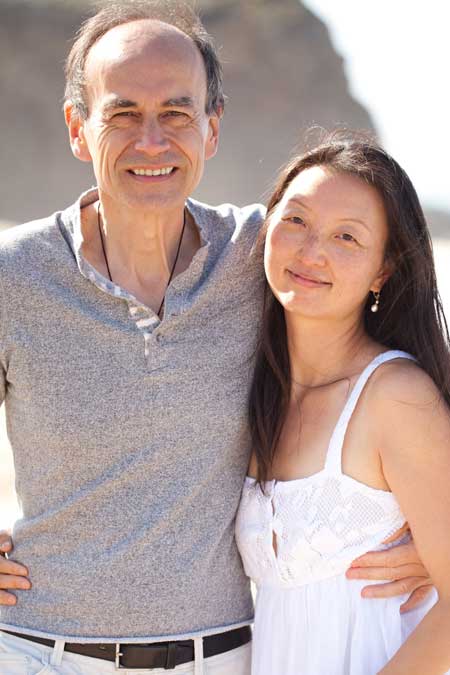

Dr Thomas Sudhof and his Chinese wife Chen Lu. Provided to China Daily |

Behind every successful man is a strong woman, the adage goes.

Dr Thomas Sudhof, a Stanford professor of molecular and cellular physiology who just won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, credits his success in great part to his Chinese wife Chen Lu - a Stanford associate professor of neurosurgery, psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

"(She) is a brilliant scientist whose advice and insight into my work has been enormously helpful," he tells China Daily in an exclusive interview.

Sudhof is also on the scientific advisory board of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute for Biophysics in Beijing, and often travels to China for research and exchange opportunities.

When the Nobel Prize press officer called Sudhof to inform him that he had won the Nobel Prize in Medicine, the professor, who was in Spain at the time, was initially "incredulous" and then "ecstatic", he says. He immediately called his wife, who, unbeknownst to him, had already learned the news earlier when the Nobel Prize press officer called their home in California after the Oct 7 announcement by the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden.

"I did want to tell him the news myself but he deserved the joy of hearing it from the Noble Prize press officer directly," Chen says.

Sudhof shares the prize with Dr James E. Rothman of Yale University and Dr Randy W. Schekman of UC Berkeley. Each of the new laureates discovered different aspects of cell transport systems, with Sudhof contributing an understanding of how cells in the brain "talk to each other", he says.

This communication process underlies everything the brain does, from feeling and seeing to thinking and performing a movement, and understanding it better forms the basis for any future insights into neuropsychiatric diseases, he says.

Now he is working on how brain cells decide which other brain cells to communicate with and what language to speak. This fundamental issue is important not only for understanding the brain but also for insight into diseases such as autism and schizophrenia, he says.

Though the Nobel honor will certainly make his life busier, Sudhof hopes it will enable him "to be a better spokesperson for the values" he believes in.

"I don't think Tom will slow down," Chen says of her husband. "Although both of us have the tendency to stay away from the limelight, we recognize the importance of communicating to the general public the value of science and value of truth. We will both use the opportunity this prize brought to us to fulfill our responsibilities as scientists in terms of communicating with the public regarding science and education."

Chen expects her husband will remain fundamentally the same, she says.

"He is driven not by his desire for prize recognition, but by his insatiable desire to understand truth," she says. "That will never change."

Sudhof is very conscious of the potential for scientific discoveries in China, he says.

"I believe that the US science community appreciates the talent and potential for Chinese science, the enormous investment in science that has been made, and the achievements of the Chinese scientists," he says. He has worked with Chinese scientists both in China and the US.

Chen says: "They are contributing a great deal to science and all other aspects of society. We are living in an era of globalization."

But the Nobel winner notes Chinese scientists still face difficulties in the field.

"The most important goal for Chinese science is to achieve a good independent process of peer review, ideally using international senior scientists," he says.

However, he believes China will produce a Nobel prize winner in the sciences in the coming years. That development will come sooner if Chinese leaders place a greater emphasis on the value of scientific truth over the pursuit of "strategic investments", he says.