|

|

|

The dragon's head - the eastern end of the Great Wall - seems ready

to

take a great gulp from the sea at Shanhaiguan.

|

|

|

Photos by Liu Xuanqi / for China Daily

|

The Great Wall began as a defensive barrier for the Middle Kingdom but stands today as a cultural icon synonymous with the Chinese nation. But the Wall is much more than monumental stone and mortar, as Eric Jou and Liu Xuanqi discover. For many people, it is a way of life.

Dynasties. Governments. Revolutions. Standing watch over China for all these hundreds of years, the Great Wall has seen it all.

While much of the Wall still stands today - especially the parts connecting the fortified towers that long defended the Ming capital, Beijing, from northern invaders - large sections are slowly being consumed by time and the elements.

But in Hebei province, the once-neglected great dragon is slowly being restored to its former glory with the help of the locals who call the area home.

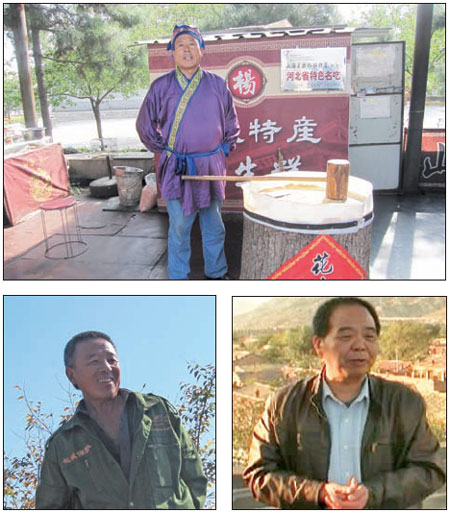

Yang Jun, 52, has lived most of his life by the Wall at Shanhaiguan, and he is still there, performing a smashing display of peanut brittle.

"My family has been here for three generations, over 140 years" says Yang. "We've been making and selling our peanut brittle at Shanhaiguan since my grandfather's time, and now I am making it."

Having been in Shanhaiguan for so long, Yang has become a part of the Wall just as much as the Wall is part of his business. Yang says that when CCTV and other media shoot videos along this part of the Wall, the filmmakers often make him part of the story.

Dressed in his period clothing, Yang pounds cooked peanut brittle, chopped peanuts mixed with honey, which he then sells. Yang says travelers originally ate the snack because it was full of nutrients and lasted well for long journeys. Now Yang's snacks are popular as a fun food, but with a show.

"This recipe has been passed down my family, and we have been selling our snacks to locals and tourists alike for a while now," says Yang with a smile as he gives his mallet a rest.

Over the years, Yang says, he has seen a vast difference in the area, the biggest change is the reconstruction effort to "rebuild or remake" Shanhaiguan to its former glory.

Like most parts of the Great Wall, Shanhaiguan was built as a military installation, and the town around it was a garrison for troops.

At one time, Shanhaiguan was called the "First Gate Under Heaven", because it was considered the first point into China on the Great Wall.

Originally many separate shorter defense walls built over the ages, the Great Wall was united under General Qi Jiguang during the Ming Dynasty (13681644) as a means to repel invaders. Qi directed the construction of bigger and better fortified towers along the Wall to hold troops.

He also organized border towns to help sustain the soldiers stationed on the Wall and allowed soldiers' families to relocate to these nearby communities. Soon the towers along the Wall acquired the names of the families who stood watch in them.

With his green jumper and weathered face, Zhang He-shan could have been easily mistaken for a volunteer trash collector. But Zhang, 56, is part of a group of volunteer historians of the Great Wall, as well as one of its caretakers in Dongjiakou village.

Zhang claims to be a descendant of one of the soldiers who laid down the original bricks of the Great Wall, and he recounts with great pride his family ancestry and his upbringing along the Wall.

"In 1568, my ancestors were brought over by Qi Jiguang to build and stand guard on the Wall," says Zhang. "We have been here for 12 generations, and I grew up listening to my parents and grandparents talk about the Wall and how my ancestor helped build it. It is a story I tell my own children as well."

A simple man, Zhang smiles happily as he walks up to his family tower. Despite not having a higher education, he says, he is happy to be educated along the Wall through family stories and history.

Zhang says he has walked up to the Wall nearly every day of his life. He's worn out more than 500 pairs of hiking shoes over the years, he boasts, because of the rocky path that leads up to the wall from Dongjiakou.

While other sections of the Great Wall are well-maintained tourist attractions, the edifice here in Northeast Hebei is in disrepair. Climbing up to towers and the wall itself requires a trek up a rocky trail up before reaching a set of stairs that lead to a tower.

"This section of the Wall is special to me, I feel like some one has to take care of it and it's my responsibility to do so," says Zhang. "Sometimes I give guided tours to foreigners who visit. Other times I just walk, take pictures and pick up the trash so as to keep the Wall clean for the next group of tourists that come by."

Cleaning up after careless tourists and giving history lessons to all who would listen has earned Zhang a reputation, but his greatest contribution to the Wall may be his meticulous record keeping.

Before the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), Zhang found stone steles in the nearby towers with names that belonged to the builders of the Great Wall. He wrote down all the names in the hopes of finding out more about that part of history. Unknown to him, he was preserving history as many of the steles were wiped out later.

"I contacted someone who could help me read the inscriptions on the slabs," says Zhang. "This professor helped me read them and I copied down the names on each of the steles in each tower, I'm glad I did because, years later, the steles were removed or destroyed."

Devoting himself full time as a volunteer Great Wall Protector, Zhang gets a stipend of 1,500 yuan ($236) a year. He has become sort of a Great Wall celebrity in his area, a go-to person for the folk history there. He has been interviewed countless times and featured in many a documentary, including the docu-drama The Great Wall of China by the British Channel 4.

Located close to Huailai, the west end of Hebei, Jimingyi is an old postal outpost town from the Great Wall's glory days as a fortress barrier. Jimingyi was built as a relay station for trade and as a rest stop for officials who were looking to inspect the wall.

At one point, Jimingyi was a prosperous walled town. Now, however, it is run down with portions of the wall falling apart.

Over time, Jimingyi's history has faded from memory as its original inhabitants and their descendants were displaced and replaced. But before the community's history disappeared completely in the sands of time, the sleepy city got a second chance.

Li Anmin, a 58-year old historian and researcher, came across Jimingyi during a routine cultural artifact census.

"When I first arrived in 1979, the area was poor, rundown, and parts of the walled city were falling apart," says Li.

"I was shocked by the disrepair and how the villagers were living, so I started looking more into Jimingyi. I noticed a lot of historical significance to it, such as it was once one of China's oldest postal relay towns."

Among the stories Li was able to document: The Empress Dowager Cixi once stayed overnight in Jimingyi while fleeing a Beijing besieged by the forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance.

In 1986, Li and the government started to fix up Jimingyi.

Li's ambition is to rebuild Jimingyi, and in his passion for the area he has involved his daughter in his work to learn more about the town, through the local history that he can track down, as well as historical documents about Jimingyi.

Li is not originally from anywhere along the Wall, but his passion for Jimingyi's history prompted him to move to nearby Zhangjiakou.

Much like Zhang, who lives in the village of Dongjiakou on the other side of Hebei province, he lives in hope that the Wall will regain its former glory, its history will be preserved, and "the town itself will flourish as it once did when the Great Wall was still used."

You may contact the writers at sundayed@chinadaily.com.cn.

|