Living life to the Mex

(China Daily)

Far from the heat and humidity of Mexico, a little restaurant stands smug along one of the many polished, cobble-stoned streets in one of China's most popular tourist destinations.

Step inside Taco Bar and you could well be transported from the edge of Lijiang's old town to La Paz, capital city of the state of Baja California.

The walls are painted in screaming shades of blues and yellows, the upholstery is bright, the bar stocks everything from Jack Daniels to Malibu and a Mexican chef prepares the molletes listed on the menu to ensure the place wears a "traditional Mexican look where travelers can come and relax".

David Ramirez Ramos opened Taco Bar last year with help from his aunt Rosa Maria, a 51-year-old chef who, now she is divorced, feels she is "like the wind, free to go" wherever she pleases.

David and Rosa typify the Mexican immigrant making the most of the opportunities China offers.

In 1972, Mexico was one of the first Latin American countries to appoint an ambassador to China, says Ambassador Jorge Guajardo. Yet there are no more than 950 Mexicans here, according to registrations at the embassy's consular department in Beijing.

Most of those, says Guajardo, are students or businessmen like the men behind the Bimbo bread and Corona beer - very unlike David and Rosa. David first came to China in 2006 to teach English and arts at a summer camp in Lijiang. Eight months later, when he returned to Mexico, he knew he wanted to make his life here. When he returned, however, he found himself in a challenging environment. He didn't speak Chinese and admits: "It was a risk".

"At first, I didn't know what to do," says the 30-year-old. So he took up teaching jobs, all along nursing the thought of starting a restaurant some day.

The opportunity materialized when a bar owner he had come to know well said he wanted to sell his business.

"A lot of people had told me that Mexican food would be a hit with the Chinese, so I asked my aunt, a personal chef in the US, to join me," he says.

Rosa adds: "It was an exciting offer and given the bad economy in the US, I thought going to a new place would be a good idea.

"Compared to being a personal chef, running the restaurant is easy but I find it difficult to get used to the hard beds and the Chinese toilets."

At the other end of the mainland from Lijiang, is another restaurant dishing out Mexican cuisine. Pedro Garcia, 29, started El Mexicano in Shanghai because when he was a student he "truly missed good Mexican food".

Pedro grew up in Matamoros, a town in northern Mexico that is closer to Houston, United States, than to the capital, Mexico City. He came to Beijing in early 2004 and did a major in international business, hoping to eventually join a multi-national.

He returned to Matamoros but decided not to stay. "There were plenty of jobs but not as much opportunity as in China," he says.

In June 2007, Pedro returned, this time to Shanghai, where seven months later a 40-something female Mexican chef was working the El Mexicano kitchen.

"I spoke a little Chinese and although it was difficult, getting started was not all that bad," says Pedro.

He recalls being anxious on the opening day - Jan 9, 2008.

"I was a tad scared because it was a big investment. But by lunch time, we were serving 35 people in the 44-capactiy restaurant," he recalls.

"All day, I waited on tables, taking orders and serving. At the end of the day I was exhausted but happy."

Pedro says the language barrier is one of the most challenging aspects of running a business in China. That, and not being able to find the right ingredients, is why El Mexicano doesn't serve typical Tex-Mex dishes like chimichangas.

"Once, we couldn't serve a particular cake because the powder we use was unavailable," says Pedro. "Our supplier could not replace the stock for an entire week and customers kept asking for it."

Pedro believes there is huge potential for a chain of El Mexicanos as only 10 percent of his customers are Mexicans and 50 percent are Chinese. For now, though, he is just happy living in China, "learning something new every day, from eating Chinese food to understanding new proverbs or learning new laws".

For Miguel Diaz, a 37-year-old Mexican-American, one of the reasons he has stayed in China is "because people have been really friendly and helpful over the years".

Diaz, who teaches at an international school in Shanghai, didn't have it easy. "My initial reaction when I moved here was 'What have I got myself into'."

That's because before he relocated from Los Angeles to Shanghai, he had come to China for a vacation in 2002.

"The China I saw then was very different because I stayed in 5-star hotels with fabulous views. When I relocated, I saw the real Shanghai - one building blocking the next," says Diaz, also a lyricist.

Being unable to communicate, he says, was the "most difficult part" and yet he had no problems making friends.

"Compared to Americans, Asians and Chinese are much more open to new cultures and new people," he says.

"In Shanghai, I ended up making a lot of friends easily. People simply come up to you on the streets, in the subway, at the restaurants to offer their business cards, chat and even take you out for lunch."

Diaz, who is waiting to publish a book on his experiences as a member of an ethnic minority in America, also likes the fact that when in China he looks at the United States "from the outside looking in".

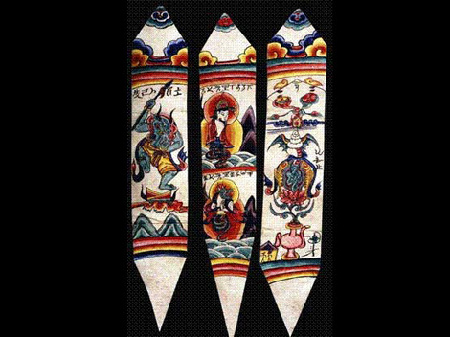

At the same time he relishes being a social observer in China and remembers an incident from his travels to Tibet.

"When a traditionally dressed, old man approached us, I thought he'd ask us for some money. Instead, he asked if we had any pencils or pens because the town children were short of writing instruments."

Diaz says his China adventure never ceases to amaze.

(China Daily 03/09/2009 page10)