|

|

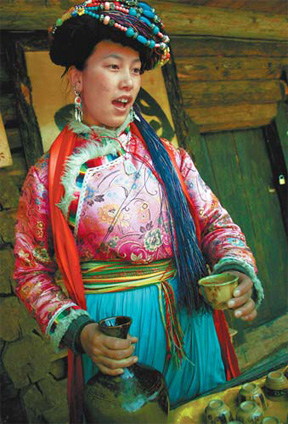

A Mosuo woman offers home-made wine to tourists in Lugu Lake, a must-see place in Lijiang. Long Tao

|

Accustomed as I am to traditional Chinese cuisine with its regional variations, I was thrilled to find I could feast on delicious and wholesome foods while traveling across Yunnan.

I was pleasantly surprised to find on an almost daily basis wonderful and fresh homegrown or wild produce, prepared the way any ordinary farming family has been doing for centuries.

Imagine my initial surprise when walking along the picturesque alleyways of the UNESCO heritage site Lijiang city when a street vendor offered me sunflower seeds freshly dug out from a large sunflower pod cut from its stalk that very morning. What better sustenance than to crack a soft shell and bite into the fresh raw taste of a natural sunflower seed?

Or take the humble potato, grown by every farming household in these parts and stored through the winter months to augment daily meals. Imaginative stall-holders at the local market turn the spud into delicious snacks, shoestring bundles frying gently in a wok over coal fire nestling alongside roughly cut French fries, next to a basketful of crispy thin slices of deep-fried potato chips liberally sprinkled with salt and chili powder.

I didn't realize rural Yunnan is mushroom country until I discovered how delicious and ubiquitous a wild mushroom hotpot is in touristy Lijiang. When asked by a waiter which wild mushrooms I would like in my hotpot stock, I confessed that I had never seen such a dazzling array. Suffice to say, the boiling hot mlange of fungi soup was a feast for the senses.

I chanced upon a young farmer displaying a basketful of Matsutake mushrooms (song rong, pine mushrooms), telling me he had hand-picked them on a dawn trek through the pine forests rimming Lugu Lake northeast of Lijiang.

Matsutakes are revered as the "king of mushrooms" in Japan. But the young man only wanted a tiny fraction of its Tokyo price for his morning labor.

My love of this rare delicacy was requited when I took a bunch to a home-stay caf and had it steamed in its own juices and barbequed with a separate order of garlic chips.

Having an egg for breakfast must be the most banal first meal of the day anywhere in the world, but this reached new heights for me in Yunnan. There were freshly laid chicken eggs for sure, but it was a peddler sitting by a rustic wooden bridge cutely named The Bridge for Lovers on the shore of Lugu Lake whose array of eggs blew me away.

Here he was offering boiled pale-green duck eggs that contained more goodness than their chicken counterparts, as well as gigantic goose eggs each big enough to feed four.

I found one of the best cooks at a lakeside restaurant where the proprietor netted a live carp from her pond and effortlessly whipped up a lip-smacking fish stew.

She first fried garlic, ginger, dried red chili and pepper in oil coaxed from some fatty air-dried belly pork.

She then plunked in chunks of the freshwater fish to simmer gently in a stock. She served the finished product with a dipping sauce of chopped fresh garlic, cilantro, green onions, dried red pepper flakes and salt moistened with a little of the soup.

Every Frenchman or Chinese knows the sweet taste of frog legs, but when I spotted an item on the menu called "beautiful ladies" at a bed-and-breakfast lodge run by a Mosuo family, I had to ask what it was. The little girl helping out at the eatery replied: "Deep-fried frog skins - because they look like ladies' legs!" The crispy-crunchy snack made from leftover frog leg dishes turned out to be utterly delicious.

There are more surprises when your taste buds move up the animal chain. When you enter a friendly farmer's home, you will be asked if you'd like a chicken or duck for lunch. Your answer will mean life-and-death for the farm animal in question.

After I chose "chicken", a young boy chased one down in the courtyard, which his father slaughtered with a knife and his mother cooked in a big cauldron of soup over a wood fire by the hearth. It was a most tummy-warming meal I have had in a long time.

Another time, I saw an item on a local restaurant menu called "wild chicken". Upon learning that it meant wild pheasant, I had the chef make a soup prepared the traditional Chinese way - that is, by slow boiling the whole wild fowl in a medicinal herbal broth.

The resulting fragrant golden stock floating with delicious meat is a culinary experience worth writing home about.

In Yunnan's countryside, you can very easily find natural foods that are wild or small-farm grown without encountering any processed or manufactured items pushed from a factory conveyor belt.

And with very little effort, you can feast on wholesome foods anywhere, anytime, simply by eating what the locals eat.

Simple Yunnanese peasant fare easily qualifies as wholesome by any modern, trendy yardstick for healthy living.

By Choo Waihong

|