Where women rule

(China Daily)

|

Mosuo people live around beautiful Lugu Lake in a "women's world", the only surviving matrilineal community in China. Li Li |

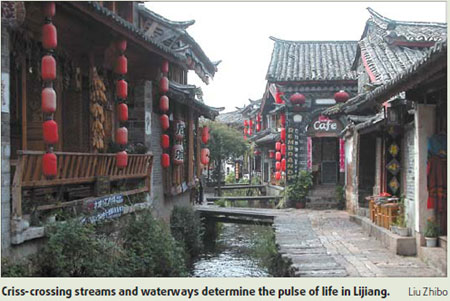

Soon after setting foot in the ancient town of Lijiang, on a high plateau in mountainous northwest Yunnan province, you will likely come across a large water-wheel and hear ethnic tunes, then catch sight of a group of dancers dancing in the middle of the square.

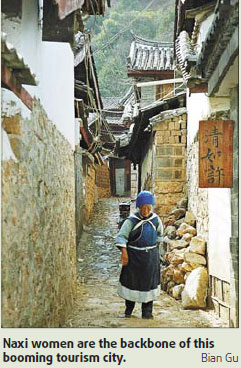

They are elegant middle-aged women who move with an easy grace in long, gray-blue pleated skirts. These ethnic Naxi women come to town and dance, after finishing morning chores around their homes and farms, to earn a few tourist dollars.

As you stroll down the cobbled lanes that wind their way alongside brooks fed with fresh spring water from Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, north of Lijiang, an enterprising woman peddles wild strawberries picked that morning.

Down an alleyway en route to the heart of the old town in Sifangjie (Square Street), where visitors to Lijiang gather to feel the pulse of this World Heritage Site, a map-seller calls out in several foreign languages, while her sister hawks sightseeing tours.

If you are a keen shopper you will note the tiny stores lining the narrow streets are run by women shopkeepers and sales assistants, weaving shawls or tidying up native handicraft on the shelves.

When you tire after meandering up and down this hilly town gawking at intricately carved wooden doorways and cornices of two-story Naxi-designed wooden houses, it's time to find a restaurant and eat some fresh food, like the five mushrooms hotpot I tried at a restaurant run by women.

Then, just when you think you will not be surprised any more, you wander into a busy market where only the locals roam and find rows of meat stalls staffed by robust cleaver-wielding Naxi women known as the "lady butchers".

And so it goes, until the light comes on and you realize that almost everything in this old town - rebuilt painstakingly from a devastating earthquake in 1996 - is "manned" by the women folk.

It is not only the Naxi women who run the economy in these parts. The same goes for the spectacular mountainous region known as Tiger Leaping Gorge.

I was met by a 50-something grandmother from the Bai minority group, who was to be our mountain guide, after a bumpy ride in a minivan along a hazardous rocky mountain road.

Our guide had infinite patience as she waited for me to struggle forward on the steep and at times perilously narrow ledge perched above the raging Yangtze River below. She had time to light up a cigarette and make a phone call on her mobile each time I stopped to catch my breath in the thin mountain air.

When at last I climbed onto the rocky promontory named Tiger Leaping Rock, from where the legendary tiger leapt across the Yangtze at its narrowest point, my guide explained that accompanying me was just a short and welcome break for her.

With her absentee husband away working she was the only person on her farm planting and harvesting the wheat, corn and vegetables and tending to a menagerie of two horses, six pigs and a few chickens and ducks.

Nowhere else is woman power more pronounced in this southwest province of China than in the small farming communities of the Mosuo ethnic group, dotted around the pristine and beautiful Lugu Lake, set high up in the Xiaoliang mountains, on the border between northwestern Yunnan and southwestern Sichuan.

Mosuo is not called "Women's World" for nothing - it is, after all, the only surviving matrilineal community in China. Every tourist has a sketchy idea of how this "country without fathers and husbands" has existed for thousands of years.

You learn from the guidebooks that each Mosuo household is an extended matrilineal family, all of whose members are related to each other on the mother's side, headed by a grandmother.

Fathers have little to do with the children, if anything. The women are the property owners and decisionmakers, while the men labor in the background.

On checking into a lodge by the lake, I had to negotiate the rate with the eldest daughter of the grandmother, not the man standing behind her, who turned out to be her brother and was told by the sister to take my luggage to the room.

The next day, it was the same lady who directed her younger brother and a nephew to row me in a dugout wooden canoe across the clear blue lake.

On the way back, the pair confirmed that grandma is the one who collects the money earned by each member of the family from the various farms and tourist work available. She is also the one who holds the purse strings and doles out pocket money when needed.

As for the "walking marriage" practice in the Mosuo community (where a woman is free to choose her lover and ask him to stop seeing her when the relationship is over) you can catch a facsimile of this practice re-enacted nightly as part of the song-and-dance story of the Mosuo people.

It is performed by community performers at tourist theaters in the bigger villages of Luoshui. What you do not see behind the scenes is the community-based effort of putting on the show, with each household contributing performers and sharing the profits at the end of the night.

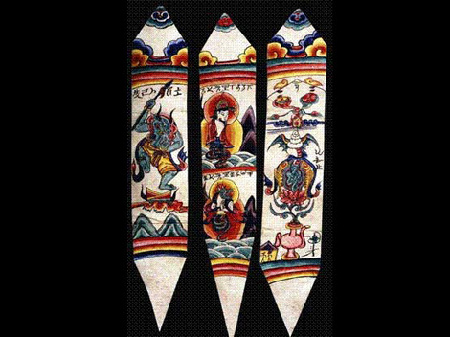

There is no better evidence that woman power still exists in this part of Yunnan than in the way the Mosuos worship. On the 25th day of every seventh lunar month for what is the grandest festival of the year, Mosuo families in all their finery trek up Goddess Mountain to worship at the shrine of Gemu, their female deity, then feast, sing and dance to celebrate their womanhood.