An end to matriarchy?

(China Daily)

|

It is the women who do the heavy farm work among the Mosuo. Geiru Yongqing's mother harvests wheat at her family's plot in Yongning, Yunnan province. Photos by Zhang Yi / for China Daily |

The traditional way of life in Yongning township's only remaining traditional Mosuo village faces a fight for survival. Zhou Wa investigates.

"I don't want to marry the guys in my village, because we traditionally have a 'walking marriage'. I prefer monogamy," says Geiru Yongqing, a 19-year-old Mosuo woman in Yongning township's only remaining traditional Mosuo village, Walabie in Lijiang City, Yunnan province. Yongqing is not alone. Mosuo youngsters from the Naxi ethnic group have their own ideas about the traditions of the last matriarchal society in China.

Mosuo men and women typically don't marry and live together. All sexual relationships are called "walking marriages" or "visiting relationships", which means the man may spend the night with a woman, but leaves in the morning and works for his mother's family during the day.

This means he has responsibility for his sisters' children on his mother's side.

Yongqing says she doesn't like the idea of this kind of childcare for her kids, when she has them, as they will not see their father enough.

She has some other gripes too.

"My brothers usually make money outside the village in big cities, so they don't have enough time for the children, either."

Although Yongqing is the youngest female in her family and is set to replace her 54-year-old mother and take charge of the family, she says she would prefer to have a nuclear family.

Wujin Zhima, 12, says she doesn't want to be the matriarch of the family either.

"My mom and grandma are tired every day, as they have to do all the farm work, house work and weave," she says. "I would prefer to go to university in a big city and become a dress designer."

"It is normal for these young people to raise objections to their traditions," says Sun Dajiang, of the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences, commenting on the trend of Mosuo men and women leaving the village and changing their lives.

"It is natural for young Mosuo people to want to escape their poor and difficult lives, especially Mosuo women."

Sun says mainstream education and learning that life elsewhere is more comfortable and colorful, naturally interests young Mosuo people.

Cao Jianping, head of the Lijiang Lugu Lake Mosuo Culture Research Association (MCRA), however, is concerned that traditional Mosuo culture will die out.

"People are the essential component for Mosuo's big families. When they leave, the family dies," Cao says.

In response, some Mosuo people are trying to protect their culture.

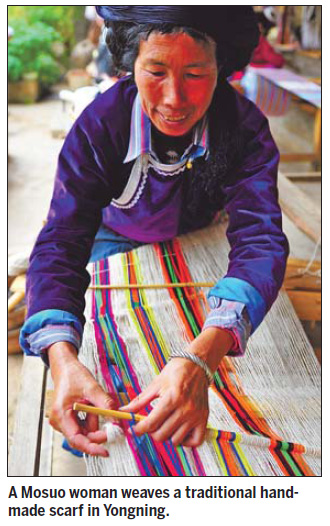

Aqi Duzhima, for example, has been weaving and selling traditional Mosuo scarves since 1993 and under her guidance many Walabie women have an extra source of income by weaving.

She hopes to build a Mosuo handicrafts factory to create income for Mosuo women and encourage them to return to the village.

"When people come back, hope returns that our traditions can be passed on," Cao comments.

To help out Duzhima and others like her, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the central Chinese government, and cosmetic firm Jala Group, recently launched an initiative offering support and guidance to start and maintain a successful business.

The focus of this initiative is to provide the management skills to organize a workforce and make products by providing training workshops.

"We hope the program will help the local community build a sustainable culture-based ethnic minority business model, reduce poverty and instill a sense of pride among Mosuo women toward their culture that will cause them to protect it far more than policy alone could", says Silvia Morimoto, UNDP deputy country director in China.

Other Chinese institutions and individuals have also come up with initiatives to protect Mosuo culture.

For example, Liu Shiye, a senior high school girl in Beijing, opened an online shop that sells traditional Mosuo hand-made scarves after visiting the ethnic group in late 2010.

Despite these efforts to protect Mosuo culture, there are still concerns about its continuity.

"Old cultures are eventually superseded by modern mainstream cultures, it is an unavoidable trend," says Song Xiaoqing, a former officer with the Ministry of Culture.

"We cannot deny that our culture may disappear one day in the future," says MCRA's Cao. "But what we can do is slow down the process."

Even so, the UNDP's Morimoto is positive about the future of Mosuo culture.

"Ethnic minority groups possess rich and distinctive cultures, which, if properly preserved and managed, can be a strong driving force for development," she says.

"Since some cultures are only one generation away from extinction, the challenge therefore lies not in slowing down the process, but in convincing the people of its true value."

(China Daily 09/27/2011 page18)