|

Innovation in the treatment of benign enlargement of prostate may benefit men in China's countryside and across the globe

It has been more than a decade, but Jiang Hansheng still remembers the look on the face of "a Beijing expert" when he explained a method he had experimented with for years to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia, or an enlarged prostate gland, a condition that occurs frequently among men aged 60 and older.

"The expert simply smiled and shook his head, and my heart sank," Jiang, a retired urologist from Shandong province, recalls.

The dismissal represented nothing new or surprising for the doctor. Since the early 1990s, he had spent 10 years researching and performing a procedure called balloon dilation of the prostrate. He had also expended a lot of time and effort attempting to convince his peers and superiors that the method was an effective treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The condition is not life threatening and is rarely painful, but it can cause a range of problems, including the need to urinate frequently and involuntary urination.

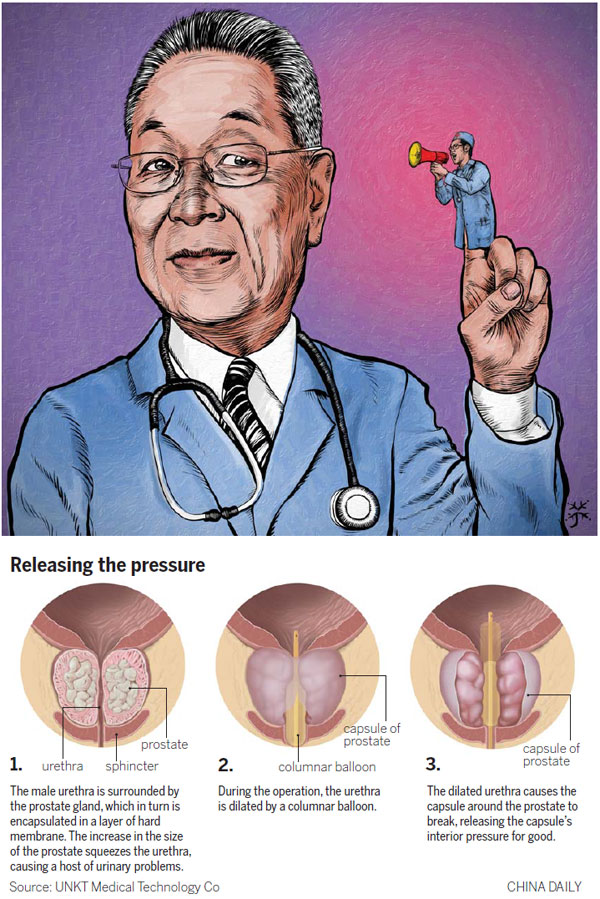

"The urethra is partially surrounded by the prostate grand, which in turn is encased in a hard capsule of membrane," says Tian Long, an urologist at Beijing's Chaoyang Hospital. "With the total volume inside the capsule remaining unchanged, an enlarged prostate means a narrower space for the urethra, which in turn gives rise to many urinary symptoms concerning storage and voiding."

Tian is one of six patent-holders of a surgical procedure called transurethral columnar balloon dilation of the prostate, known among doctors as TDUP. The procedure, which usually takes about five minutes, involves inserting a long, column-shaped balloon into the section of the urethra enveloped by the prostate and then inflating it. Ideally, the dilated urethra exerts pressure on the capsule around the prostate, causing it to break in minutes.

"Once broken, the capsule can never grow back together, and therefore all the inner pressure is released once and for all. This means the urethra will feel no pressure, however large the prostate becomes in the future," Tian explains.

"The short procedure time has sharply reduced the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, such as thrombosis and fatal pulmonary embolism (blood clots in the lungs), which has a high rate of occurrence among senior patients," he says, comparing the procedure with electrotomy, the use of high-frequency electric current to cut or destroy tissue, and laser surgery, the predominant methods of treating BPH. "Both methods take about an hour to complete and involve the removal of all or some of the prostate."

Although the procedure sounds quick and easy to perform, gaining wider acceptance among the medical community has not been easy for Jiang, or those who believe his method has a future.

"The idea of prostate dilation was not my invention," he says. "It was first introduced to China from the West in the 1980s. Back then, the balloon was shaped like a ball, not a column.

"Many urologists in China, including myself, performed the procedure, but the results were far from satisfactory, and the procedure was completely abandoned after just one or two years."

It was forgotten by everyone except Jiang, who trusted his medical instincts and began a decade of experimentation with the procedure.

In the 1990s, Jing Xuejun, who worked with a medical equipment manufacturer that was owned by the government at the time, not only witnessed Jiang's endeavor, but also got involved.

"Jiang came to us and asked whether we could make the balloons he needed," Jing recalls. "Over the next few years, we created a bewildering array, all sizes and shapes, for him to try."

The balloons produced mixed results, but Jiang was unable to pinpoint the exact reasons behind success and failure. His inability to provide plausible explanations meant he and his method were rejected, and sometimes even ridiculed.

While some traces of the ridicule still linger, at least there is an explanation now, according to Guo Yinglu, honorary chair of Peking University's Institute of Urology.

"Long-term results depend on whether dilation of the urethra causes the capsule of the prostate to break or not. If yes, then in most cases, success is guaranteed; if no, then it's inevitably a failure," the 86-year-old says. "Why? Because if the capsule is not ruptured, even if the urethra is dilated by the entry of the balloon, it will be squeezed back to its original state by the surrounding prostate tissue once the balloon is removed."

For the past decade, Guo has headed a research team, including Tian, which has focused on TUDP. After patenting the procedure nationally in 2012, the team is now gathering more clinical evidence and promoting the procedure among doctors across China, from national to county level.

Reflecting on the experience of Jiang, who had knocked on many doors before meeting him about 12 years ago, Guo believes the biggest obstacle for any innovative Chinese doctor - low-level doctors especially - lies in conventional thinking.

"We're so used to retracing the footsteps of our Western counterparts that any digression from their trodden path risks being dismissed as unworthy of serious investigation," he says.

According to Tian, electrotomy and laser surgery have long been championed as the global "gold standard" for BPH treatment. "Traditionally, the capsule of the prostate is a no-go zone. People worry that insertion of the balloon will exert pressure on the sphincter, the ring of muscles that sits right below the prostatic apex (the base of the prostate), whose proper function is essential to the control of urination," he says. "Any potential damage of the muscle may lead to urinary incontinence, or involuntary urination.

"But in practice, this (damage) has very rarely happened, and that may be because the balloon is quickly moved further into the urethra to relieve the pressure on the sphincter. It's a matter of just a minute."

And the procedure is significant not only because it offers an entirely new concept of the enlarged prostate treatment, but also because the treatment is tailor-made for people who live far from big cities and are not financially well-off.

"Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, many rural patients opted for my method simply because they didn't have any other choice," Jiang says. "Electrotomy and laser surgery didn't appear in China's county-level hospitals until the early 2000s."

Worldwide, 60 percent of all men aged 60 and older suffer from an enlarged prostate gland. For men aged 70 and older, the figure rises to 70 percent; and for men aged 80-plus, it is 80 percent.

Around 2004, Guo attended a medical conference in Qingdao, Shandong province. "I asked a participating doctor what he thought of Jiang's cause, and the answer was, 'Don't waste time on him. He's a madman.'"

Jiang, who retired in 2011, appreciates the work undertaken by Guo and his staff, and the support they have shown.

"They have made sure my life's work isn't wasted and have proved that, in the end, I'm not completely mad."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|