The language of wood

Zhou Ning, an artist who lives an isolated life in rural China, is presenting his carvings in Beijing. Deng Zhangyu reports.

For about 20 years, Zhou Ning has lived in the countryside in East China's Shandong province, dedicating himself to one thing - chiseling blocks of wood.

The 48-year-old artist seldom visits cities unless he has to. But he came to Beijing at the end of October for the start of his solo show at the Yilian Art Center.

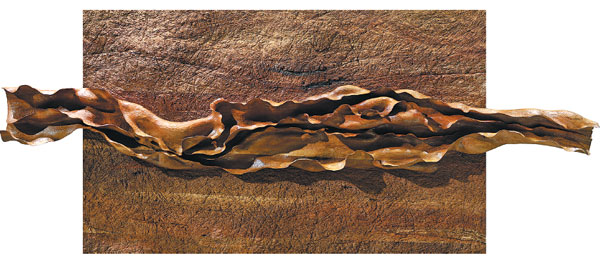

|

A woodcarving from the series The Wind by Zhou Ning. |

The ongoing show, titled True Words: Carving a Path to Self-Cultivation, features 28 woodcuts, among which the heaviest is around 150 kilograms.

Unlike many other woodcuts that focus on carving out delicate patterns or making the surface smooth, Zhou's works show how he moves cutting tools through wood.

"Everything has a soul. I can feel it when I touch the wood," he says.

Every time Zhou selects a block, he brings out his tools to feel the fibers.

Zhu Xuchu, an art critic who has known Zhou for a decade, says the artist treats every piece of wood as a living creature, "letting it speak for itself" based on each block's shape, hardness and color.

Zhou has created a unique world of woodcarving, using wood as a medium to present his moods through his skillful cutting techniques, Zhu adds.

Zhou's studio is in Shiqiao village, not far away from Taishan Mountain in Shandong.

The artist's works also connote Taoism, a subject he is fond of.

Speaking of his life in the countryside, Zhou says it is cheap to have a big studio and collect materials needed for his work.

More important, the noise made by woodcarving does not disturb others, as Zhou usually works at night and sometimes until early morning. During the day, he guides his apprentices, who have physical disabilities. Some of them have worked with him for years.

In 1995, Zhou graduated from Shandong College of Arts in Jinan and taught art at a special polytechnic school for people with hearing and speaking disabilities.

"All the students were eager to learn a craft to make a living. I taught them woodcarving because it was an affordable craft for them," he says.

Zhou majored in mural painting in college and had hoped to be an oil painter one day. But while teaching his students woodcarving, he discovered their gifts and decided to keep on developing their potential, as well as building on his own skills.

In 1997, Zhou and his students held a show at the National Art Museum of China and made a big splash. But many students' parents stopped them from studying further because they thought art was useless when those who practiced it were hardly able to make a living.

For many years, Zhou himself lived in poverty. Along with his students, he lived a simple life in the rural areas and continued on the artistic path.

He made various cutting tools himself to carve out sharp lines, sweeping curves and hollowed-out parts in wood, day after day.

"The carving knives for me are just like pens. It is very easy to master the skills after decades of practice," he says.

It's common for him to spend several years on one piece. If he loses the inspiration to carry on with a work, he will stop and wait for months - even years - to resume.

"There are lots of unfinished works piled up in my studio. A good piece needs time and patience. Also, it needs my sincerity to treat it," he says.

Each time he has had to move from village to village, mostly due to the development of cities nearby, it takes dozens of trucks to transport his unfinished pieces.

After his first solo show was held in Shanghai in 2015, collectors started to visit his studio in Shandong and buy his works.

The show in Beijing is his second solo show, with works produced in the past few years. When displaying his work at the Beijing show, Zhou wore a pair of cloth shoes and carried his tools in an oversized cloth bag.

"It needs power to carve out a heavy piece. Sometimes my students assist me," says Zhou.

He refuses to use electric tools, which he says cut wood in a mechanical way.

"When I touch a piece of wood, I can sense what it has and I know how much I need to cut and where to cut," he explains.

Zhou is a man of few words. He communicates with his apprentices in sign language and spends most of his time in the countryside, away from the clamor of cities.

Han Yingxue, curator of the show, says Zhou's wood pieces speak to the "inner mind of a man concentrating on his art without intervention from the outside world".

Contact the writer at dengzhangyu@chinadaily.com.cn

Shandong Culture and Tourism Consumption Season

Shandong Culture and Tourism Consumption Season Culture, tourism sectors pick up in Shandong as epidemic wanes

Culture, tourism sectors pick up in Shandong as epidemic wanes