Spending 27 years living alone while teaching students in a small, remote school would be a tough task for any ordinary person, let alone for a fingerless man. But Chen Haiping has done just that.

The 51-year-old teacher at a village school in Shanxi province was selected as a role model in a campaign launched by e-commerce giant Alibaba, and the story of his selflessness has been held up as an example to all.

Born without fingers or toes, Chen met the principal of Liujiashan village school by chance in 1990 and became a substitute teacher, as instructors in rural areas were in desperate short supply at the time.

"I was 23 then and nobody recruited me after I graduated from a middle school. The job provided me a monthly wage of 50 yuan ($7.77). I was very satisfied," Chen said.

To be a good teacher, he has overcome many obstacles. He had to get rid of his accent and make his Mandarin more standard to teach pinyin, the Chinese phonetic alphabet, and he got up early each day to attend a larger school 10 kilometers away to learn from teachers there before returning to his school before class began.

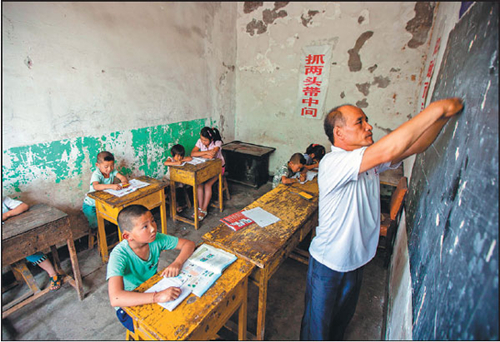

But his biggest challenge was writing on the chalkboard. Without fingers, he had to hold the chalk between his palms to write.

"It was a painful process. I got blisters on my palms, and the chalk always fell to the floor," Chen recalled.

Located on a hillside in Liulin county, his school is very different today from 20 years ago. The two-story building that was once alive with 100 or more chattering students now sees a total attendance of only seven - Chen, who is the teacher, cook and cleaner - and his six students, three of them preschoolers.

Chen teaches them all in the same classroom.

The situation at Chen's school is not unusual. As migrant parents take their children with them to cities, fewer students attend village schools. A government report said that more than 60 percent of children ages 6 to 15 were living with their migrant worker parents in 2013.

In the early 2000s, some rural schools closed or merged to improve conditions. Most village children were sent to schools in towns or cities. A few were left in "ghost schools" like Chen's because the journey to a bigger school is too long or prohibitively expensive.

"The quality of education in ghost schools is not as good as in bigger ones, but they are still important. Without them, some students would drop out," Chen said.

Feng Qiangqiang, 11, is the oldest student in the school. His stepfather, a coal miner, is never home, and his mother is chronically ill.

"The family is unable to send him to a better school," Chen said, adding that this is part of the reason he refuses to leave. The educational authorities once transferred him to another school, but he soon returned.

Chen was surprised to be chosen as a role model and delighted to be awarded 5,000 yuan, more than twice his monthly salary.

But the joy was short-lived. He worries he may be the last guardian of his school as the tough conditions scare good teachers off.

"I will keep teaching even if there is only one student left," he said.

|

|

Chen Haiping teaches at the Liujiashan village school in Shanxi province.Photos By Feng Shuai / For China Daily |

|