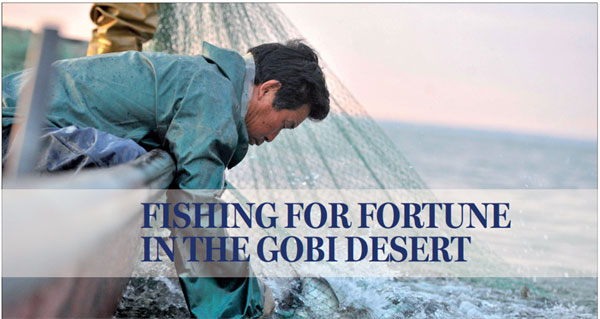

For the fishermen of the Xinjiang Uygur region, netting the fish and marketing them is just as important as protecting the environment

Seven families of fishermen have traveled from the Yangtze, China's longest river, deep into the Gobi Desert to earn a better living.

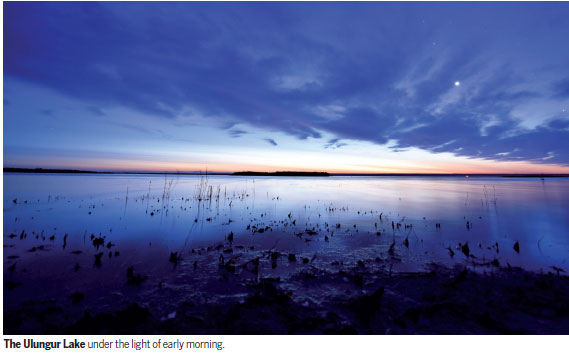

Seven boats and seven tents serve as their homes along the shore of Ulungur Lake, known as "the sea in the Gobi", in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

"I have heard that it's easier to 'dredge money' here," said Chen Guishan, 50. The thinly populated region has been attracting hardworking people to help drive local development.

Chen and his wife, Zhao Youlan, were born, married and fished along the Yangtze River in eastern China until nine years ago, when they joined the "desert fishermen team". They hoped their paradoxical new job might bring them prosperity.

Ulungur Lake in the north and Bosten Lake in the south are the two major fishing bases in Xinjiang. The bodies of water, about 1,000 kilometers apart, are two of the largest freshwater lakes in China and cover a total area of 1,600 square kilometers.

To make more money, the seven families lead a nomadic life, just like local herders. They fish in Ulungur Lake in spring and summer, and then migrate to the warmer Bosten Lake when autumn comes.

Their work in Ulungur begins after an annual fishing moratorium ends. The day begins at 6 am, when the sky is still starry. Chen and his 25-year-old son, Chen Zhaozhu, walk out of their tent, put on waterproof pants and life vests, and set sail.

In the light of dawn, they spot other boats sliding through the water. Chen keeps sailing toward the center of the lake. All the way they hear nothing but motors vibrating rhythmically.

After about half an hour, the boat arrives at the fishing area. The father and son drop anchor and cast their nets. They don't need speech to communicate. When the son hauls a net out of the water, the father selects fish that are large enough to be put into the boat's hold, and throws juvenile fish back into the water.

"We must be sustainable. We must set juvenile fish free to let them grow, so we must pick them out one by one," the older fisherman explained.

It is a lucky day for them. Two catches make a full load for their boat. On less lucky days, they have to cast out at least eight times, Chen said. Happy with their catch, they start the engine and sail to the market dock.

In this line of work, selling is as important as fishing. When they arrive at the market, they see many others are already there. The typically quiet father becomes talkative. Eager to sell, he puts his catch straight on a trader's scale. He is reassured only when the trader nods in acceptance.

The freshly caught fish will soon be on tables in Urumqi, the Xinjiang capital, as well as cities nationwide thanks to China's fast-growing logistics services.

Ulungur has clear water and abundant fish, said Zhao Jingsong, head of the local fishery administration. It has long been a tradition for locals to fish there.

"The lake brings us wealth, so we must protect the environment here," Zhao said. "We follow strict fishing restrictions and regulations to protect it as a natural resource."

The father and son return home, content with the 1,600 yuan ($240) they have earned from about 1 metric ton of fish. When they arrive, Zhao Youlan is preparing lunch. Fish with vegetables is a typical meal for the family, she said.

Like many who work in the fishing industry, Chen and Zhao Youlan suffer from severe arthritis, caused by years of repetitive strain. They live about 20 km from town, so they rarely go there for shopping or entertainment. When at home, Zhao Youlan cooks and mends the fishing nets, which she considers the best way to relax.

Many fishermen take a nap after lunch while their wives play mahjong together. But Chen doesn't take a break. He starts to repair the family's leaking tent.

With the approach of winter the family will soon move to Bosten Lake, where they will continue fishing until warm weather allows them to return to Ulungur.

"I have spent most of my life afloat, so I want to spend my old age ashore," Chen said. "When I have enough money, I will buy a house and come to anchor."

Xinhua

(China Daily USA 11/17/2017 page7)