Peter Nelson's work is about bits and pieces. He separates a craggy rock face from a mountain, a tree from the landscape it is planted on, a T-shaped pillar from the expressway it supports.

His work, he says, is similar in ethos and temperament to Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) paintings. "If you look at Yuan Dynasty landscape art closely, they are studio paintings. You have a mountain here, a tree there it's a whole repertoire of rearranged subjects."

The young Australian who graduated from art school in Sydney in 2006 and was resident in Beijing's Red Gate Gallery till September, has filled the walls of his warehouse-like temporary studio with rows and rows of line drawings on pages of a pocket-sized notepad.

The sketches were made during his recent tour across China. He would pick up a province and try and soak it up like a sponge over two to three weeks. He traveled extensively in Hunan, Guangxi, Shanghai and Taiwan before landing up in Beijing, studying the landscape, visiting museums, checking out contemporary art in exhibitions and bookshops.

The Chinese odyssey was laden with surprises - mostly pleasant ones. For example, Chinese artist Yang Xu showed Nelson around in Chongqing. "It's amazing to see a whole lot of good art happening in a city that does not even have an art gallery," says Nelson.

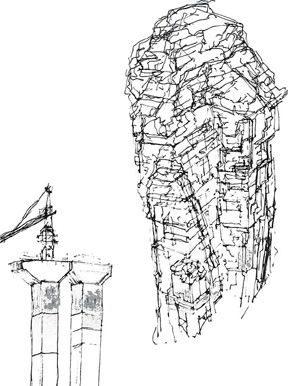

His own work done in Beijing is mostly in black and white line drawings using micro-tip pens, Chinese ink and white water color, done on A4 paper. There is a harmony between what man appreciates in nature and what he makes of it in his paintings. It's about rocks morphing into buildings, foothills of a ridge spreading out to resemble a courtyard.

|

Artist Peter Nelson is surrounded by line paintings (below) in his studio at the Red Gate Gallery. [China Daily/Jonah M. Kessel]

|

Nelson has added one more dimension to his work by replicating his drawings in the form of sculptures. Using recycled materials from soft cartons, he has built models of the facetious rocky mounds, a feet or two taller than his own six-feet frame. He has also recorded the entire process of building from scratch.

While he does not want to feel the pressure of having to produce something for the galleries at the end of his three-month residency, the cardboard sculpture is a piece he would not mind showing.

"I came here to make new ideas," he says, with understated conviction. "It's good not to have to always make things that are successful."

"Residencies are about buying time," he adds. "They afford you a unique opportunity to focus. But if I manage to produce a substantial amount of work at the end of three months, I might want to show it."

Looking at the volume of work plastered on the walls of his studio, he might be persuaded to do that.

Nelson's fellow residents in Beijing's Red Gate Gallery - Frances Barrett, Kelly Doley, Kate Blackmore and Diana Smith - also began as students of art in Sydney. But they chose to chart a slightly different trajectory, trying to explore the space between "visual culture, performance, art and theatre". The quartet, who went to the University of New South Wales, soon fell for the lure of art in motion.

Brown Council, their company, work in both video and performance art, the two media often dovetailing into each other. Their work is largely about subversion. For example, the piece entitled The Joke Bit, produced in 2009, set in a real-time speed-dating situation, exaggerates the bizarre and reductive turns romance might take "in a society obsessed with speed".

Getting to see contemporary Chinese performance artistes in action was China's obvious attraction for the energetic foursome, all in their mid-20s.

But the two-month residency in Beijing is also "like going into hiding, not having an obligation to show your work," says Smith. For the four young women, living in the same studio space is also an opportunity for "intense sharing, an opportunity to speak out without feeling self-conscious," as Barrett puts it.

The impassioned brainstorming done during their time spent in Beijing is evident in the writing on the wall - sheets of paper on which the artistes have jotted down their thoughts in large, bold letters. Ideas seem to germinate and fructify around themes as regular as "Birthday Party" - placed at the center of the page - running away in different directions as if by a centrifugal force.

Four costumes in vivid orange, blue, green and black - two identically long rectangular pieces of fabric with almost no cuts, held together by stitches on the sides - are hung on the wall.

This resonates with the quartet's most recent performance piece, What Do I Do?, in which they "investigate the mythology of the performance artist and the absurdity of costuming enacting 'performance anxiety'."

The China sojourn was full of striking surprises, some in obvious places like the Freedom exhibition at 798 by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, where a giant hose, suspended in air, unleashes a powerful water jet, striking randomly on the surrounding metal walls. The Uygur woman in flashy theatrical costumes dancing feverishly at the Temple of Heaven was almost as exciting.

At the end of the two-month residency, the group of four is eager to get back home and begin work. "We feel refreshed, we're just about beginning to get the ideas. We can feel them rising inside us," says Blackmore.