Education

Logging off, then rebooting a childhood

By Wang Wei (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-11 07:59

|

Large Medium Small |

|

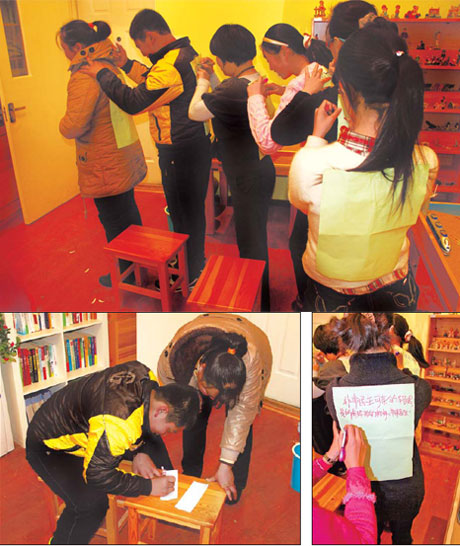

Clockwise from top: Children and parents write positive messages using the backs of others; one message reads "my mom is a role model for all mothers"; Xiao Nan records how he thinks the sessions have affected him as his mother watches. Photos provided to China Daily |

Playing computer games and chatting online used to be Xiao Nan's (not his real name) biggest diversion in life.

The seventh grader from Beijing Wenquan No 2 Middle School lost himself in a virtual world for at least four hours every day after school and up to 12 hours on weekends.

His obsession with the Internet caused a slump in his academic studies and his parents became worried.

They recall how in the summer of last year, his father agreed that Xiao Nan could play computer games for two hours daily. This promise wasn't kept and an argument escalated into a fiery fight.

"After he shouted at us, he would turn to the Internet so he could release his anger," said his mother, surnamed Xie. "He wouldn't listen to what we were saying."

This situation was unchanged for three years until the family took part in a trial program, aimed to handle Internet addicted youngsters, which was initiated by the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning at Beijing Normal University.

On Jan 3, the last session of the program, together with three other families, Xiao, 13, and his parents went back to school. They were asked to close their eyes and picture the best times the family had spent together.

Xiao and his mother thought about a family dinner they had recently, which was the first time they had spent together in a long time. His parents were migrant workers and had to work long hours to survive.

On Jan 3, the last session of the program, the families played together. Xiao and his father were asked to stand on a newspaper and keep folding it until it was too small. When that happened, they were told to find a way to continue.

While most families opted for carrying the child, Xiao and his father failed as they could not agree to work together.

Their response was expected, according to Dr Fang Xiaoyi, who is in charge of the program.

Fang said that while most Internet addiction camps utilize a militarized management style with students forced to clear their addiction, he believed that family harmony was more important.

"We don't put the tag of Web addict on these children," he said. "We create a real life setting so the kids can realize that some of their habits are wrong and get rid of them voluntarily."

According to Fang's research, adolescent Internet addiction is often the result of a broken family.

"When youngsters feel that they can't relate to family members and friends, they seek contacts in a virtual world," he said.

The Beijing trial program began on Nov 20 and lasted six weeks. It had six sessions with each one lasting for one and a half to two hours. Fang is confident that after the program, the participants will cut the time they spend on the Internet and the family bonds will grow back.

His attitude is based on a similar program his team ran in Inner Mongolia last year. The six-week intervention saw 17 participants from a school in Inner Mongolia lower their weekly surfing time from 30 hours per week to around 10.

Xie has been happy to watch her son mature with the weekend sessions. She said he started expressing care for his parents, such as asking whether they were tired after work or if they had had dinner.

But Xie said the main difference was that he now only spends a few hours each week online.

"When I get home I will see him doing homework rather than playing games and it makes me feel great," she said.