Life

In step with the times

By Liu Yujie (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-01-11 07:59

|

Large Medium Small |

|

Neiliansheng shoemaker He Kaiying shows three apprentices how to hand-stitch the sole of a shoe. [Photo/China Daily] |

Related video: In step with the times

Neiliansheng is a traditional Beijing shoe brand that has stepped through changing times. Liu Yujie visits the flagship store to find out more about the time-honored name and what it has planned for the next decade.

Established as a shoemaker for the officials, wives and concubines of emperors who ruled the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Neiliansheng continues to be a favorite of many top leaders and celebrities, as well as the rest of us.

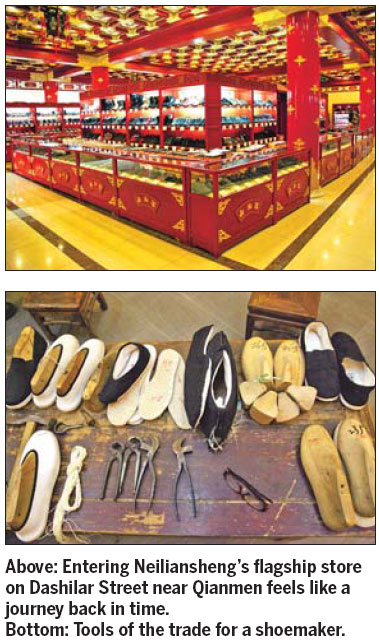

There is no surprise that the main store is located in Dashilar Street, a pedestrianized area south of Qianmen. Dashilar Street boasts a history of about 500 years and is a prime location for Beijing's traditional brands, such as Ruifuxiang silks, Tongrentang pharmacy and Majuyuan hats.

In Chinese, nei means the imperial court and liansheng suggests being promoted through the official ranks. Zhao Ting, who founded the brand in 1853, did so with the hope that anyone who wore his shoes would climb high up the bureaucratic ladder.

The shop's windows prove his success. There are copies of shoes worn by the late Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai and the exhibition center on the third floor has walls of photos and text that describe the changing styles of shoes in China.

In the center of the building is a stone block with a worn-out corner, made by craftsmen pounding hundreds of thousands of shoes. Also on display is a book of measurements of officials' feet during the Qing Dynasty.

He Kaiying, a master shoemaker in his 60s, is the fourth descendent of a family of Neiliansheng craftsmen.

He believes that Neiliansheng's cloth shoes are perfect for the modern consumer. Natural materials allow for the foot to breathe, while being extremely light. The vamps - the part on the top of the foot - are black satin that stay smooth even after heavy use.

With quality comes expense though and while a regular craftsman might charge 1,000 yuan for a pair, those from a master are closer to 3,000 yuan.

"Price varies according to skill and experience," He said. "It takes years of practice to make a perfectly comfortable pair for an individual. It is just like going to the hospital; an expert costs more."

He said that a hand-made sole requires at least 80 stitches in every 1.69 square inches, evenly distributed. Attention also has to be paid to the tightness of every stitch, depending on the shape of a customer's foot.

In order to make a shoe for the rack, a craftsman needs only half a day. However, tailor-made products can require up to one month.

He said Neiliansheng has many customers with irregularly shaped feet, most of which are old ladies with feet disfigured from the practice of foot binding.

This group is diminishing because the feudal tradition has ended, but there are plenty of new groups that Neiliansheng is focusing on.

Embroidered shoes for women are popular. The vamps are made from silk and the soles are cloth or leather. There are a variety of patterns that include orchids, bamboo, peonies, chrysanthemums, plum blossoms and mandarin ducks.

"We have a special design team, some of which are professional designers returning from France, that creates new styles and patterns," said Wang Qiang, assistant manager of the store.

He said there is also a large choice of patterns for children born under the different animals of the Chinese zodiac. Images of dragons sell the best because parents believe they will bring fortune to their children.

"I've also noticed young people showing an interest in wearing cloth shoes with a qipao," He said, referring to an elegant Chinese dress that was popular during the late Qing Dynasty and the early 20th century.

"This is good because cloth shoes will then improve their health status while maintaining traditional Chinese culture."

To safeguard the legacy, He has just finished taking three male apprentices through more than three years of training. His first lesson was simply to get his students to calm down.

"It was difficult because we all like being energetic," said Ren Chenyang, 27, who was one of the three apprentices. "But as the time ticked by, I fell in love with the craft."

Ren said the most difficult lesson he learned was not a practical one such as stitching, but a sense of responsibility toward his country.

"The younger generations have a responsibility to carry on traditional Chinese culture," he said.

"It makes me happy to see parents bring their children to the exhibition center because I know it means a promising future for us all."