Belichick following familiar script

By Associated Press in Houston (China Daily) Updated: 2017-02-04 15:18Patriots coach has taken cue from other members of exclusive club

Bill Belichick values his team's overall culture ahead of its individual parts.

He rules the New England Patriots with an iron fist, yet instills them with a sense of family.

He can appear heartless - quick to say goodbye to those who no longer fit in - yet he is deeply loyal.

Belichick has hard and fast ideas about how to run his team, but he's never against learning and adding bits of others' expertise to his own repertoire.

On Sunday in Houston, he can set himself apart by winning a record fifth Super Bowl title as a head coach.

Chuck Noll of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Tom Landry of the Dallas Cowboys and the University of Alabama's Nick Saban all know the feeling of helming dynasties, as do Gregg Popovich of the NBA's San Antonio Spurs and former UCLA basketball coach John Wooden.

It's a very exclusive club.

"Xs and Os are the price of admission," said sports historian John O'Sullivan, founder of the Changing the Game project, who speaks often about the importance of coaching in society.

"With great coaches, the first thing they do is connect. When you connect with people, they'll run through a wall for you."

Can Belichick really be called a people person?

The same might have been asked about Noll, Landry, Saban or any of these coaches, whose time facing the public usually involves abbreviated segments with the media during which their main goal is to not reveal anything important about their game plan - or much about themselves.

The effort - and sometimes, accolades - they get from their players says more.

Terry Bradshaw couldn't stand Noll on their way to winning four Super Bowls with Pittsburgh. Only years later did the Hall of Fame quarterback concede that he benefited from Noll's coaching.

"Did I respect him? Of course I did," Bradshaw said last year.

"Like him? No, I didn't like him at all."

Among the 15 blocks on Wooden's famed "pyramid of success" is self-control - an attribute that applies to the players as well as the coaches and general managers choosing them.

Popovich, in a recent talk he gave to a group of coaches, spoke of the virtually mandatory requirement to resist talented players who are more focused on themselves than the team.

"That's not easy," he said. "You have to follow through, be good to your principles. That person who's going to be good, who has potential, is probably going to get you fired."

A lot has been made this year of New England's decision to part ways with two key cogs in its defense - Chandler Jones in the offseason, then linebacker Jamie Collins, who was traded away to winless Cleveland in October. That defense still allowed the fewest points in the league.

Belichick is hardly the first coach faced with those sorts of choices.

In the 1970s, Landry spent a season shuffling between Roger Staubach and Craig Morton at quarterback. Eventually, he recognized the Cowboys could only succeed with one of them, and he chose Staubach. Morton, who was enormously popular, was traded to the Giants.

"Sometimes it is unfortunate to have to make such a decision," Landry said at the time. "But it is important to clear the air so there is no speculation on it from week to week."

Tom Thibodeau, coach of the NBA's Minnesota Timberwolves, spent time with Belichick a few summers ago and said he marvels because "the infrastructure is so strong" - one factor that allows great coaches to say goodbye to key players without missing a beat.

"You either conform and become a team-first guy, or you won't be there long," Thibodeau said.

"I think every player really wants discipline. And they want to win. So when you give them the environment, they'll usually respond in a positive way."

But while the great coaches demand discipline, they also figure out ways to get their teams to bond.

Legendary Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi had a well-earned reputation as a taskmaster, and yet one epiphany that took him over the top was the concept, virtually unheard of at the time, that the word "love" really did belong in a locker room.

This year's other Super Bowl coach, Dan Quinn of the Atlanta Falcons, has discussed his quest to turn his group of players into a "brotherhood."

Belichick will never be mistaken for being warm and fuzzy, though maybe Vince Wilfork's tweet after parting with the Pats in 2014 painted the best picture about the sort of atmosphere the coach has created: "We are always family," Wilfork wrote.

And while great coaches have some hard and fast rules about how they want to run their teams, the best of them always keep an open mind toward learning.

Famous are the stories of Belichick's willingness to go the extra mile - especially in the film room - from the time he got his first NFL job, as an assistant to Colts coach Ted Marchibroda in 1975.

"The impression he made on colleagues was almost universally favorable - open-minded, incredibly hard-working, absolutely committed to being a little better every day ... a master at using film," wrote David Halberstam in his 2005 profile on Belichick, The Education of a Coach.

Another great coach took note of that.

Before Saban started winning his five national titles at Alabama, he was Belichick's defensive coordinator with the Cleveland Browns from 1991-94.

"I thought I knew something, and really found out that I was really in a position to learn a lot," Saban said.

"That time in Cleveland probably helped me as much as anything in developing the kind of philosophy and organizations that have helped us be successful through the years. "I attribute a lot of that to Bill Belichick."

|

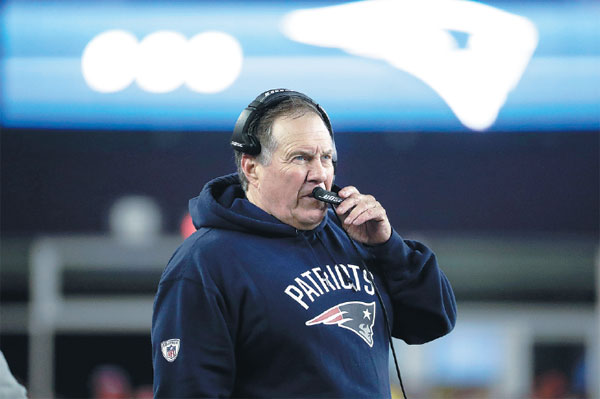

New England Patriots head coach Bill Belichick talks on his headset during the second half of the Patriots' victory over the Pittsburgh Steelers in the Jan 22 AFC championship game in Foxborough, Massachusetts. Matt Slocum / Ap |

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express