Spoiled for choice

By Mike Peters (China Daily) Updated: 2017-02-17 13:46A new food hall in Beijing combines pop-ups, food artisans and a quest for variety to give visitors plenty to choose from, Mike Peters reports.

Under the long roof of this former Beijing factory you can find grilled grass-fed lamb. French-style artisan cheese. American-style barbecued ribs that smell like heaven. Elegant pastries. Beer and wine. Picture-perfect vegetarian meals in a bowl.

But Hsu Li is quick to shake his head when someone suggests that Yu Food and Lifestyle is a "food court".

"That's what you have in the basement of a mall," he says, "where the cheap fast-food is."

The co-founder and general manager of Yu, which now houses 22 small kitchens, says it's best described as a "food hall" of great variety.

The spaces are rented out to entrepreneurs who have a pop-up concept, he says, but people have different reasons for setting up shop here. The facility is also known as "The Crib", and while some vendors will take advantage of the shared roof, space and delivery platform to eventually launch a free-standing shop elsewhere, others are looking for something more long-term than the usual pop-up. Longtime Beijing cheesemaker Liu Yang liked the idea of having a retail space where he could engage customers, and so did the team at Mengba Warriors - a lamb wholesale operation in Inner Mongolia. A few meters away is Yaksa Thai, one of the busiest shops in the hall, which is run by a group that previously worked in a popular small Thai restaurant group and decided to strike out on their own.

Some stalls house existing brands looking for a branch in the Gongti area, including the patisserie Glacage, Mr Shi of dumpling fame (he's serving up noodles here) and Classic Snack, which has four outlets in its home province but wanted a toehold in China's capital. Carne, a shrine to meat, is a vestige of The Smokehouse, a barbecue restaurant Li and his brother Eli operated until recently in Sanlitun, which still has a cafe outlet at Tsinghua University.

Alongside each row of vendors are different blocks of seating: tables for two, banquettes for four, even conference-size tables for parties or working groups. Half of the customers seem to have migrated from Starbucks: They are solitary souls who eat or drink absently while their attention is glued to laptops and cellphone screens.

Price levels vary, from inexpensive Chinese plates that run about 30 yuan ($4.40) to more crafted creations that can cost 70-100 yuan. On the top floor, an upscale bar offers uncommon brands and a revolving menu that features a particular type of liquor seasonally.

With this much variety, The Crib attracts quite a few customers who haven't decided what they want to eat.

"It's kinda like Sanlitun that way but not as overwhelming," says international student Yolanda Wang. "I can walk around, see what looks good, smells good, and then decide."

We can't resist doing the same on several visits.

The first time, we gravitate to Yaksa Thai. The staff beckons us as eagerly as hawkers in a street market. The menu has big pictures, the food is familiar, the staff speaks English and there is lots of comfortable seating around. We make a quick trip to the bar upstairs to grab some beers to go with our pad Thai and curries, and we're all set.

Other venues are a little less accessible, especially for foreigners who don't speak Chinese. The language challenge starts at the cashier - all vendors here accept payment through a common system. Customers can buy a card with credit good at any of the 20-odd restaurants - the minimum is 100 yuan on the card - or use WeChat or Alipay to access the central till.

That control has its advantages. Besides running the payment system, the hall management approves menus and tacitly monitors quality.

"Legally and permit-wise, we're all one restaurant," says Hsu Li. "So if one of our vendors screws up on cleanliness or something, everybody can be shut down." Hsu and his partners also look for vendors "who have a go-to specialty that they do very well," he says, "and we don't let them copy each other. So if you make lasagna and you're not selling well, and the guy across the aisle is selling pita sandwiches like gangbusters - a hypothetical example, you can't start selling pita pockets to cash in on your neighbor's traffic. In a real example, that's why Mr Shi - a dumpling sensation at his original hutong location - is selling noodles here; a dumpling maker had set up shop in Yu first.

On another visit, we're tempted by the aroma of Mengba Warriors' grilled lamb - and the macho-looking cow-horned vessels on the counter that turn out to contain horse wine.

Horse wine?

If you're new to Mongolian culture, this is horse milk spiked with some sort of baijiu, the Chinese white spirit that fuels merry-making at banquets but has added practical value on the chilly plains populated by ethnic Mongolians: the potent booze keeps the milk from freezing. (It makes the milk more fun to drink, too, but it's an acquired taste, even for Chinese.)

We nibble a few skewers and move on to Le Fromager de Pekin, where French-trained cheesemaker Liu Yang is making Sicilian-style pies topped with his artisan dairy creations.

Liu has developed a substantial base for his cheeses, from creamy Camembert to hard-cured varieties. While his array of cheeses is sold in expat-oriented supermarkets and weekend food fairs - and embraced by a number of restaurant hotel chefs in Beijing and Shanghai, this is the first retail outpost of his own.

Besides a chance to interact with the people who eat his product, Liu is keen to expand awareness of artisan cheese among Chinese. That's why he's opted to sell pizza.

"This is not a big dairy culture, so many Chinese aren't familiar with the craft of making fine cheese," he says. "But everybody knows pizza - and it's a product that uses a lot of cheese."

On our most recent visit, we discovered what may be the food hall's most colorful offerings: Power bowls at Nooxo.

"When you go out to dinner with a mixture of vegetarians and meat eaters," says Nooxo manager Jairo "Jay" Jimenez, "you generally have to pick a restaurant that caters to one or the other."

Nooxo's focus is on vegetarian and vegan offerings, he says, but meat can be added to any dish.

"The focus is on taste," he adds. "I don't really like vegetables at all, so I'm a good test case."

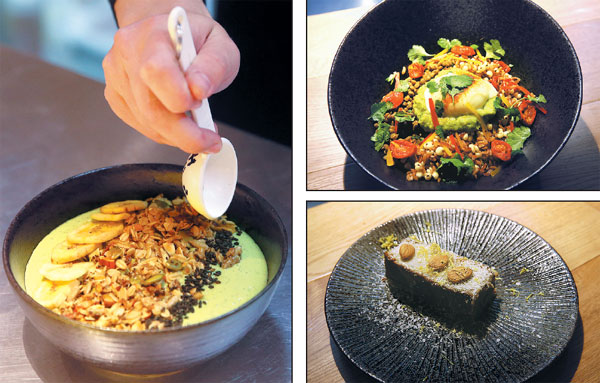

The restaurant's name comes from an indigenous Amazon tribe and means "a drink". Most of Nooxo's offerings are drinkable or close: Soups, smoothies, and smoothie bowls dominate the menu. The power bowls have names with a little hubris, such as the Lentilnator and the Grainbow.

To appeal to customers who are lactose-intolerant - and Chinese who don't have the habit of consuming much dairy - all dishes are dairy free, using soy instead of cow's milk and coconut cream instead of conventional heavy cream. Dates are used to sweeten mixtures instead of sugar or honey.

The results are delicious.

"Every shop here has a signature product that will bring people back," says Hsu Li.

Contact the writer at michaelpeters@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Clockwise fromabove: At Nooxo, a Hulk smoothie bowl ismade fromdried banana, housemade granola and black and white sesame seeds, while the Lentilnator bursts with color thanks to guacamole, cherry tomatoes andmore. Desserts aremade with ingredients like almond flour, honey, dates and coconutmilk. Photos By Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express