Giving a red packet

By Hatty Liu (China Daily Europe) Updated: 2017-02-19 15:24Lots of cash changes hands during China's annual Spring Festival, and it has economic implications

The giving of cash gifts to relatives and friends probably ranks alongside food, family, travel and TV galas as a pillar of the Chinese Spring Festival season. Known as 压岁钱 (yāsuìqían, "money against misfortune") when given to children, or simply 红包 (hóngbāo, "red envelope" or "red packet"), after the festive wrapping in which the money is presented, the many prescribed rules of giving and receiving these cash offerings are a bulwark of the Confucian family hierarchy as well as a source of anxiety to cash-strapped people with big families everywhere.

Hongbao sent through social media-oriented mobile apps tend to be token offerings to friends and acquaintances or prizes for other members of your WeChat groups to "snatch" before the total runs out.

Though WeChat has never revealed how much money has changed hands in total during each Spring Festival, Alipay reported last year that 250 million hongbao were sent through its payment system on New Year's Eve, containing an average of 182.6 yuan ($26.50; 25 euros; £21). So there's a lot of money changing hands around the nation, which provides us a fount of economic information.

|

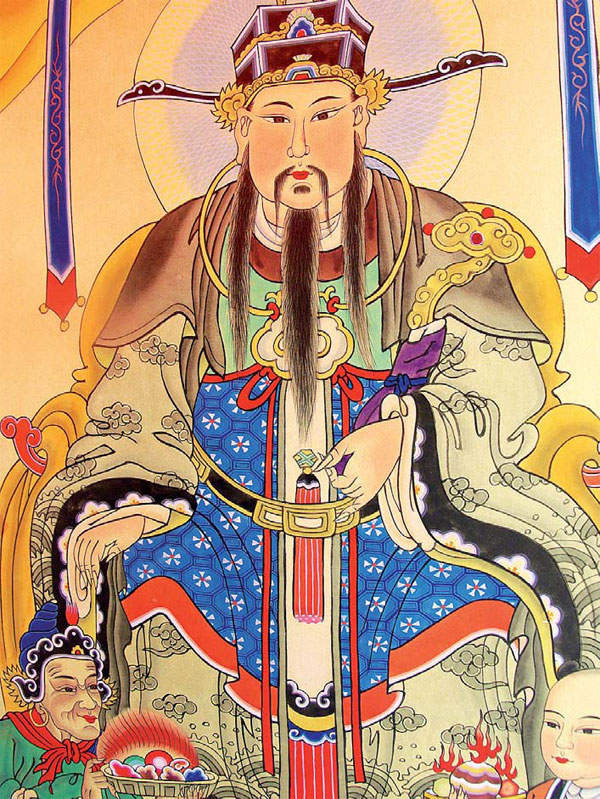

A traditional Chinese New Year painting shows the God of Wealth. Provided to China Daily |

Here are a few economic conclusions drawn from hongbao giving:

1. The value of hongbao transactions relates to regional economic conditions … except when it doesn't.

An essay circulating on WeChat titled People in Guangdong Still Give Out 5 yuan Hongbao" inspired netizens around China to "air out"

(晒 shài ) - that is, share with their social networks - the typical value of hongbao given in their home region.

As summarized by the public WeChat account Panyu WeChat By Data, the Yangtze River Delta region, an economic powerhouse region stereotyped as the home of the nouveau riche, had the highest self-reported starting value of hongbao in the nation: four figures for close relatives, hundreds among friends, with some households reporting five-figure hongbao from direct senior relatives and myth-shrouded six or seven figures among the 土豪 (tǔháo), or very wealthy.

However, any expected correlation between the hongbao largesse and general economic prowess of a region ends after this promising start, as it's economically-depressed northeastern and northwestern China that claim the next spots, with hongbao starting at 100 for acquaintances, several hundred for other relatives or close friends and going into four figures for younger, close relatives.

On the other hand, as the title of the WeChat essay indicates, the province with the highest GDP also gives the smallest hongbao in China. In response to the essay, Guangdong natives matter-of-factly informed the rest of us that it's simply the cultural practice in their region to give small, token hongbao, but give them to a lot of people: 5 or 10 yuan among acquaintances, 20 yuan among close friends or relatives, and a maximum of about 100 yuan for the closest relatives. The money is referred to as 利是 (lìshì, or lai si in Cantonese) and is given not only to relatives who've not yet entered the workforce, the elderly, or close friends as in other parts of China, but to pretty much anyone you know who is unmarried.

Netizens from the northeast also tried to justify their hongbao amounts on cultural grounds - by citing their reputation as a hale and hearty people who like to do everything, but especially the Spring Festival, enthusiastically. Additionally, the self-reports of netizens indicated variation within each region, and some were not expected to give as large a hongbao as typical of their region due to youth or lack of seniority in the family or because they had just joined the workforce.

Conversely, they have to give more than normal if they've come into good fortune, such as an impending marriage or birth of a child. The value of hongbao also varies according to your relationship with the person and their immediate family members in the context of the whole clan.

Though there's no direct correlation between a region's economic conditions and hongbao, it might be fairer to hypothesize based on these reports that economic conditions personal, familial, and regional are some of the forces determining the general amount of hongbao given, but may be influenced by less rational factors like cultural prescription, emotional distance and status.

2. Taxing corporate hongbao is a huge headache - yes, this is taxed.

Hongbao exchanged between individuals - received from your grandparents, or given to your second cousin's spouse's niece who just happened to be visiting and would feel left out - is not taxed. However, if a corporation gives out hongbao, it's taxed at 20 percent. Non-cash gifts get to bypass the tax requirements, so many employees end up bearing home gift certificates or boxes of food, condiments, and cooking oil as their Spring Festival bonus from the company.

However, the advent of electronic hongbao opens another can of worms.

In 2015, China amended its tax policies to clearly state that e-hongbao sent from a corporation to an individual should also be taxed. An example cited by the law is the practice of TV stations giving out hongbao in the course of their Spring Festival galas to viewers over WeChat as a promotional tactic; according to the new law, the taxed amount should be taken out of the amount given out to the winner, as with lottery earnings. This law is, needless to say, controversial and very hard to enforce, complicated especially by the practice of some corporations to give out hongbao to their followers on their WeChat accounts in negligible amounts that are not worth the cost of actually collecting the tax.

3. Hongbao-speak in the stock market.

In Chinese, the term "hongbao market" (红包行情 hóng bāo háng qíng) refers to a surge - usually more than 10 percent - in stock prices that takes place close to the Spring Festival, as if giving stockholders a big hongbao.

This is explained by people traditionally wanting to keep hold of their money (and by extension other assets) during the New Year. Stockholders, likewise, are averse to selling.

4. Mobile hongbao: the new frontier in economic data.

On the e-hongbao front, more definitive rankings emerge as to the top hongbao-giving provinces in the nation.

In terms of amount of hongbao sent over WeChat, Guangdong topped the list with 5.84 billion hongbao sent and received this year, followed by Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, and Zhejiang. This is almost consistent with the country's top five provinces by GDP: Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Henan. However, the correlation should be taken with some caveats, as the general practice of sending WeChat hongbao - small amounts to many people - is similar to physical hongbao-giving practices reported by Guangdong residents on WeChat.

So far, most of the analysis done regarding hongbao data collected by WeChat and Alipay has been in the realm of trivia. This year, for example, it was revealed that the greatest number of WeChat hongbao transactions was made from Guangdong to Hunan province, followed by Hunan to Guangdong, Guangdong to Guangxi, Guangxi to Guangdong, and Beijing to Hebei - possibly mirroring the economic relationship between these regions.

The post-80s generation also exchanged the most WeChat hongbao among themselves.

It was also determined that men gave more WeChat hongbao than women, to recipients of both sexes: 32.4 percent of hongbao were exchanged between men compared to 25.5 percent between women, and 24.6 percent were given by men to women compared to 17.5 percent the other way around.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express