Rural Children More Vulnerable To Delayed Brain Development

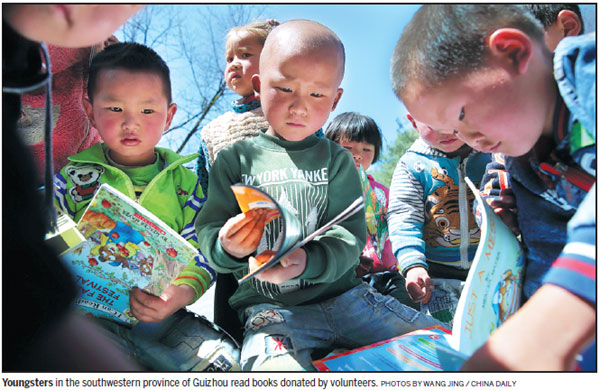

By Yang Wanli (China Daily) Updated: 2017-08-17 08:46Studies suggest that youngsters living in the countryside are likely to experience lower levels of cognitive growth than their urban peers, as Yang Wanli reports.

Since market reforms were initiated in 1978, China has moved from a centrally planned economy to one based on market forces.

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that in the past 12 years GDP growth has averaged about 10 percent a year, and more than 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty.

Despite those achievements, millions still live in poverty in the rural interior, where sturdy mules replace luxury cars and residents live in humble villages rather than tower blocks.

About 60 percent of young people in China are growing up in impoverished rural areas, and recent research suggests that, compared with their urban counterparts, they are more likely to fall at the starting line when it comes to education and future opportunities.

In June, a team from Stanford University's Rural Education Action Program published the results of a three-year research program that focused on the mental development of infants in rural areas.

In 2013, the first year, the team tested nearly 2,000 children ages 12 months to 6 in 351 villages in Shaanxi province. They used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, which measure mental and physical development and assist in the diagnosis and treatment of developmental delays or disabilities, including cognitive, motor and behavioral.

Further surveys were conducted in the following two years. The results indicated that 41 percent of the children would experience delayed cognitive or motor development if they did not have effective interaction with caregivers when they were 18 to 24 months old. The figure rose to 53 percent for infants ages 24 to 30 months.

In 2015, in association with the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the program launched the same surveys among children ages 6 to 18 months in rural areas of Hebei and Yunnan provinces. In Hebei, 43 percent of babies showed signs of significant delay in either cognitive or motor development, or both. The rate in Yunnan was higher, with 60 percent experiencing the same problems.

When the surveys were conducted in urban areas the proportion was just 15 percent.

"There are about 50 million infants in China, and most of them live in rural areas. The delay in cognitive development will weaken their competitiveness in the labor market in the future, which may influence the quality of the country's overall labor force," said Zhang Linxiu, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who led the study.

According to Liu Wenli, a researcher with the School of Brain and Cognitive Science at Beijing Normal University, interventions for children often focus on health, nutrition and stimulation during the first 1,000 days of life, because these factors result in an improved environment for brain development.

Optimal Intervention

However, the window for optimal intervention is short, according to Liu. "The number of new synapses (the junctions of nerve cells that allow electrical impulses to pass between them) peaks by about age 6 before decreasing over the next 6 years. This makes a compelling case for equitable investment in the development of cognitive capital during the early years," she said.

Scientific studies indicate that neuronal development is at its peak during the early years because 700 to 1,000 new neural connections are formed every second. The rate falls over time, and as much as 90 percent of a developing brain's final weight is established between ages 3 and 6.

"The development of the human brain continues during our entire lives. But stimulation through proper interactions between caregivers and babies is crucial because it contributes to better neural connections and improved brain function in the future," Liu said.

A study supported by UNICEF shows that about one-third of poor rural children younger than 3 have suspected developmental delays in areas such as communications, problem-solving and social or cognitive development.

"One of the challenges I see when I visit poor communities in China is that the majority of children are left in the care of grandparents who do not have the knowledge or tools to feed the brain and stimulate the social and emotional development that must happen in those first three years," said Rana Flowers, UNICEF's representative to China.

She said this period of crucial brain development requires a combination of the best possible nutrition, quality healthcare, trained staff members to stimulate different parts of the brain to connect and develop, and caregivers who have been trained in activities, such as playing music, that children can practice at home.

"Without timely interventions, these children are at risk of developmental delays. Without this specific focus, evidence confirms that as adults they will lose around 26 percent of the average adult income per year," she added.

Research has shown that investing in early childhood development, or ECD, programs yields a 7 to 10 percent rate of return, according to Flowers, who added that the returns include children's improved career prospects, as well as reduced costs for remedial education and lower expenditure on healthcare and the criminal justice system.

A growing movement

In recent years, a growing number of metropolitan parents have embraced ECD.

"Many mothers have their first baby after good preparation in terms of psychology and understanding. They want to invest more in raising their kid to be a better person with strong competiveness in the future," said Wang Wei, 43, the mother of a 10-year-old girl, who has run a center that provides drama workshops for children since 2009.

When she became pregnant 10 years ago, Wang started reading books related to ECD. When her daughter was 3 months old, Wang took a class at a community center that provided training for new mothers.

"It's important to communicate with the baby, even from the gestation period - for example, by echoing every movement. We were also encouraged to strengthen the baby's sense of balance by rocking the cradle. Those things contribute to better brain development," she said.

At age 20 months, Wang's daughter began attending a bilingual kindergarten in Beijing. When the girl was 3, Wang hired a Filipino nanny to help her learn English. A year later, she began Spanish classes.

"Spanish is the world's second most-commonly used language. Children are most receptive to language learning before age 6. Learning Spanish not only helps the development of her brain's linguistic functions, but it will also be useful if she 'goes global' in the future," Wang said.

The little girl is now learning martial arts and the piano.

Beijing has many ECD services. At Family Box, a well-known ECD center, swimming classes are very popular.

"It's the second year my baby boy has taken the class. The trainers told me that swimming will simulate the development of his brain and can also help to build a better sense of balance. If the only child in the family isn't worth high investment, who is?" said Li Meimei, 32, who has a 3-year-old son.

Lack of funding

Last year, China spent 3.88 trillion yuan on education, about 4.2 percent of GDP.

However, the amount set aside for scientific guidance about infant nutrition and development was negligible, according to Luo Renfu, associate professor at Peking University's School of Advanced Agricultural Sciences.

UNICEF's Flowers said many countries have invested a lot of money in ECD. In Sweden, for example, children can attend preschools run by local authorities from age 12.

Caregivers receive training and the system is underpinned by policies that reinforce the laws that protect maternity leave, spaces in businesses for breastfeeding mothers, equal access to healthcare and the provision of free or subsidized early education centers.

"It's important to stress the high level of government involvement. The Chinese government has made great efforts, but I am concerned about the proliferation of privately-run early childhood centers. The poor need to be supported to ensure that they have the same access, and all the centers-public or private-need to benefit from an enforced national ECD standard," she said.

Contact the writer at yangwanli@chinadaily.com.cn

- 'Cooperation is complementary'

- Worldwide manhunt nets 50th fugitive

- China-Japan meet seeks cooperation

- Agency ensuring natural gas supply

- Global manhunt sees China catch its 50th fugitive

- Call for 'Red Boat Spirit' a noble goal, official says

- China 'open to world' of foreign talent

- Free trade studies agreed on as Li meets with Canadian PM Trudeau

- Emojis on austerity rules from top anti-graft authority go viral

- Xi: All aboard internet express