A future of learning to live, love robots

By Simon Ings (China Daily)

Updated: 2008-04-10 07:29

Updated: 2008-04-10 07:29

London, 1977: the International Grandmaster chess player Michael Stean is losing to Chess 4.6, a computer program developed at Northwestern University, Illinois. Stean is steamed: he is losing. Chess 4.6 is, he says, "an iron monster". When finally he admits defeat, however, he does so with grace, declaring 4.6 a genius.

Whether we are leaving it all to the cat, or thrashing a car with a stick, we anthropomorphize as much of the world as we can. Twelve thousand years ago we took wild animals and fashioned them in our image: domestic cats have evolved babyish complexions to appeal to our love of cute.

Anthropomorphism, although apparently a sentimental tic, is central to what makes us human. A baby's realization that other people are more than animated furniture develops over time, prompted and reinforced by a pattern of exchanged glances. Long before children acquire this understanding (called theory of mind), they are fascinated by eyes, and by the direction of another's gaze. We become human only because, early on, someone treated us as human.

How complex does something have to be before it passes as human? The answer seems to be not very. A consortium led by the University of Plymouth has just won a $9.4 million grant to teach a humanoid robot named iCub how to speak English. Its theory of mind may depend less on intellectual potential than on the scientists' willingness to treat their charge like a real infant.

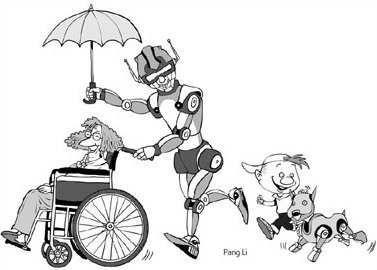

Let us hope it grows into a sociable little thing. The bald fact is, we need him. The United States Census Bureau has estimated that the nation's elderly population will more than double by 2050, to 80 million. But there are simply not enough young to look after them. A study by Saint Louis University, Missouri, shows robot dogs are as much of a comfort to the elderly as real dogs. In 30 years, robot carers will be required for practical help, as well as solace, for old people.

Domestic robots are already big business. The sale of service robots in Japan is expected to top $10 billion by 2015. Mind is the final hurdle, but robots do not have to be as clever as us to care for us, converse with us, or accompany us. They just have to be clever enough. Our instinct for anthropomorphism will do the rest.

This, anyway, is the message of Love and Sex with Robots, a book by David Levy. An International Master chessplayer, Levy was driven by his passion for artificial intelligence to lead the team that created Converse - a program which, in 1997, won the Loebner Prize, an award for the most convincing computer conversationalist.

Now in his mid-60s, Levy is bringing artifical life to sex. "Humans long for affection and tend to be affectionate to those who offer it," he says, and predicts that prostitution has only about another 20 years to run before robots take over.

Robots with credibly human bodies are already here. Add minds clever enough to handle a little language, and how could we possibly avoid loving them?

Levy argues that robots will appeal to our better natures. It has already happened. Remember those Japanese toys you had to "feed" at all hours of the night? "A remarkable aspect of the Tamagotchi's huge popularity," writes Levy, "is that it possesses hardly any elements of character or personality, its great attraction coming from its need for almost constant nurturing".

His book reminds us that humanity is an act: it is something we do. When our robots become pets, carers, even companions, we will, quite naturally, feel the urge to treat them well. When it comes to being human, we will give them the benefit of the doubt, the way we give the benefit of the doubt to our pets, our children, and each other.

Simon Ings is the author of The Eye: A Natural History The Guardian

(China Daily 04/10/2008 page9)

|

|

|

|