|

OPINION> Commentary

|

|

Japan's bailout package subtly different

By Liu Junhong (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-03-17 07:48

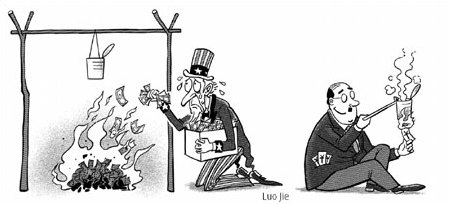

Since the breakout of the economic crisis, almost all countries around the globe have expedited large-scale fiscal, monetary, tax, even trade and industrial policies, in order to curb it. Japan is no exception. Its policy fundamentals include bold reshuffles at its enterprises, and deploying grand overseas mergers and acquisitions , ahead of their European and American competitors. First let's look at the fiscal policy. Exerting government power to apply fiscal measures, in order to pursue a "New Deal" effect, has been a characteristic countermeasure during this crisis. The difference is, however, the "fiscal march" of Japan seems to be "slier". In early October 2008, the American Congress approved the "$700 billion bailout", and thereafter, Japan also revealed its, purportedly worth almost 27 trillion Yen. The trick here is, the nominal 27 trillion Yen was in fact a framework promise. The part really funded by government, or the "real water", was only 5 trillion Yen, which can only be implemented after it wins supplementary budget approval in the Diet. Afterwards, facing the "New Deal" of the Obama administration, Japan took more countermeasures at the beginning of the year, combining the framework with the real water. The reasons why the Japanese government adopted this measure mixture is not to fool its people, but based on numerous considerations. Firstly, Japanese government debts total more than 1.5 times its GDP. Hence, if the Japanese government recklessly expands its spending regardless of sound fiscal principles, future difficulties might be even more severe, even to the extent of 2001 when Japanese government bonds were rated down, impairing the country's global competitiveness and shaking its image as a great power. Secondly, Japan's public service system has been privatized to a large extent over the past 10 years of reform. Without a large amount of "special legal persons" who can undertake government projects, the scope covered by fiscal policy has shrunken. Thus unlimited fiscal expansion may induce unequal distribution and industrial gap. Thirdly, the engine of the Japanese economy is exports, especially manufacturing. In recent years, with the long-term recovery and expansion of the Japanese economy, the profits of large manufacturers and exporters have climbed. With abundant ownership capital, these companies expect not government funds but support in industrial and foreign exchange policies.

Overseas sales and profit contributions of Japanese enterprises have generally grown. For example, the overseas and domestic production and sale in the automobile industry are almost equal. The overseas profit contribution rate of listed corporations is close to 30 percent. It is very hard for fiscal inputs to generate ideal industrial linkage effects with such a structure. Then we can look at monetary policy. Since the breakout of the subprime crisis in August 2007, it appears that Japanese monetary policy has been inconsistent with that of Europe and America. For example, when European and American central banks jointly injected huge amounts of money into the market, although the Japanese Central Bank appeared to follow suit, it actually absorbed almost all the injected money back within the same week. Japan called it "financial adjustment", which lasted until early December 2008. It seems that, in this milieu, when five central banks in Europe and America took collective action on December 12, 2007, the Bank of Japan was an exception. Especially interesting was the European Central Bank's decision to raise interest rates for the last time on July 4, 2008, before the American and European central banks shifted into the interest rate cutting camp. The Bank of Japan, however, waited until the end of October to make the first interest rate cut. It cut the policy instructed interest rate by 0.2 percent, from 0.5 percent to 0.3 percent. The financial market perceived this as the deliberate act to show a relatively high interest rate policy. When the interest rate was going to be cut, the market generally predicted that the Bank of Japan would cut it by 0.25 percent twice to resume the zero interest rate policy. In early December, the US Federal Reserve, implementing a de facto zero interest rate policy, cut the interest rate to 0-0.25 percent. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan decreased the interest rate again by 0.2 percent, to 0.1 percent, to explicitly show the market it was implementing a resolute non-zero interest rate policy. When asked by reporters, Masaaki Shirakawa, Governor of Bank of Japan, asserted that "the 0-0.25 percent interest rate of America does not mean a zero interest rate policy". Consequently the Japanese Yen appreciated against the US dollar because the interest rate gap between Japan and America had been reversed. In fact, as predicted by the market, the exchange rate of the Yen appreciated quickly from October 2008. Appreciation, without doubt, provides the best condition for Japanese enterprises to deploy overseas mergers and acquisitions. At last let's have a look at employment policy. The Japanese government, without any ambiguity, has made decisive, forceful and smart actions. Firstly, it directly appealed to enterprises to retain employees, and increased the recruitments of new graduates. Secondly, through its special administrative guidance measure, it required enterprises to make "internal transfers" to guarantee employees jobs. Thirdly, it directly formulated policies to require firms to dilute the posts and cut the surplus working load, in order to split the posts to absorb more employees. The government offers tax cut measures related to the policy, so as to lower the burdens and maintain profits of enterprises. The behavior of enterprises to keep employing not only maintains their competitiveness, but also shares the social responsibilities with the government. Although tax cuts lower the government coffers, it also lowers its unemployment allowances, as well as the political and social costs of maintaining social stability. The tax cut offered by the government to the enterprises strengthens their capability to maintain employment. Through absorbing employees and splitting posts, enterprises actually cushion social problems brought by unemployment. This is more economical than increasing tax. Though the unemployment rate of Japan and the amount of redundant labor has risen, it is still minor compared with that of Europe and America. It can be said that the Japanese employment policy has had practical success. The author is a researcher with the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. (China Daily 03/17/2009 page9) |