|

OPINION> OP-ED CONTRIBUTORS

|

|

Dogged Sichuan spirit rises above the gloom

By Victor Paul Borg (China Daily)

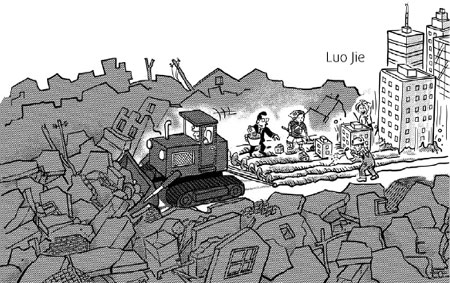

Updated: 2009-04-29 07:44 One of the largest building sites on earth lies 30 km from my house. I took a visiting friend there recently, and he kept shaking his head in wonderment. Vehicles from motorbikes to large trucks, and everything in between, snarled and heaved under the burden of building materials. Road verges were cluttered with heaps of sand, cement, bricks and bundles of metal rods. Hoots rang out impatiently. A haze of brownish dust thickened the air. My friend had never seen something so surreal. The building frenzy was a juxtaposition of chaos and efficiency, out of which new buildings arose. The new buildings were replacing the old ones - or the ones that were knocked down by the May 12 earthquake in Sichuan province. We were driving on the western fringes of Deyang prefecture, where the quake had destroyed or damaged many buildings. Hanwang, for example, used to be a thriving industrial town. But when we visited last week it was a ghost town, the general dereliction punctuated only by a few stragglers wandering among the ruins. Some of them were tourists, sauntering and gawking; others were indistinguishable, looking like lost souls in the desolate dusty streets. I visited Hanwang a week after the earthquake and it looked like a war zone, buzzing with heavy army machinery and an army command center. Today, it looks like a stricken town hit by a nuclear bomb and abandoned. The ruined houses look haunted, some bearing evidence of former lives such as posters of celebrities and clothes hanging stiffly in some bedrooms. Who knows what has happened to the people who once wore those clothes? Are they dead, or did they leave in a daze of crushed moral, never to return to the forsaken home? The old Hanwang will eventually be turned into an earthquake memorial. There are plans to build a center for the training of emergency services personnel, and a museum and quake-simulation center in the new Hanwang, rising up 2 km to the east of the devastated old town. We paused by the side of the road to take in the new Hanwang: a cluster of high-rise buildings, with excavators and earth movers and trucks moving helter-skelter among the buildings, and everything shrouded in a haze of dust, like a mirage. The road between Hanwang and Mianzhu used to be an open one with fields stretching out on both sides, and a scattering of farmhouses. Now it's lined with makeshift warehouse-shops selling all manners of building materials and household appliances. Most ubiquitous are the steel rods, laid down in bundles outside the stores - all new buildings now have to have steel rods embedded into the walls to make them more capable of withstanding quakes. That's the theory anyway, for when the earth rattles so violently as it did on May 12, walls and willpower can easily crumble. Yet the people around me aren't dwelling on the terrible disaster that has struck their lives - the Sichuan spirit is stoic. The people are now collectively building for tomorrow. It's a building boom that illustrates the link between the government and the people: a government that can organize and mobilize, and a people who rise to the occasion. In a larger way, it's a demonstration of China's gathering strength, a country that's capable of rising from a disaster quickly and confidently. Then we drove further west along country roads meandering among fields. As we passed some farmhouses nearing completion, the mountains in the Sichuan basin suddenly loomed up ahead of us. Here we found a new project taking shape, combining tourism and agriculture. An upscale hotel is sprouting at the edge of a tulip and rose plantation, and a small factory is being built to produce rose perfume, rose tea, soap and other stuff. A short distance away we went for lunch at the so-called New Year Paintings Village. It's an area that gave rise to the Mianzhu-style New Year Paintings, one of the four most famous sub-genres of New Year Paintings in China. The village, too, was destroyed by the earthquake, but now it has been almost rebuilt. The houses have been reconstructed as they were, in the traditional style, with old-style mock-bamboo tiles on the roofs, and walls covered in white stucco. The New Year Paintings, which sprawl on the exterior walls, depict mostly country scenes that symbolize the wholesome warmness and harmony of rural life. It was sunny and warm, and the air filled with trills of birds. The village is a great place to spend a weekend; some locals offer home-stays and others have set up basic restaurants. But we were the only visitors that day - despite its charms few people outside the area know about the village's existence. We had a lunch of Sichuan country food, including homemade sausage and cured meat and rice wine (bai jiu).

Villagers toasted us; the bai jiu and the sunshine pepped up the merriment. You wouldn't think that the village had been flattened just about a year ago if you didn't know. The villagers too have moved on: some spoke with prankish boastfulness about the way they were pulled out of the rubble. Others talked about dead relatives without any outward twinge of sadness. They have come to terms with what happened, and now they have bigger, better and stronger houses. Elsewhere, as we drove on, we saw farmers applying finishing touches to new buildings. The new farmhouses were sturdier than the old ones. The government gave each family a grant, and every household dug into its pocket for some more. But I felt some nostalgia: I preferred the farmhouses before the quake with their traditional tiled roofs and exterior walls of cement or white gypsum. My vision: farmhouses whose exteriors are traditional and interiors are modern. It's an impractical and vain vision. It's more expensive to build modern houses and make them look rustic, and it's only done in special places - such as the New Year Painting Village - where the government directly intervenes and pumps in extra money for the sake of heritage preservation and tourism. And I shouldn't succumb to vain nostalgia because it's all part of a larger cycle that's at play. I once read that the ethos of the people in Sichuan is formed by geography at a deep level, and the most dramatic force in the geography of the province is the regularity of quakes. Perhaps that explains the juxtaposition of a people who on one hand are famously laid-back and on the other industrious and stoic. Now the people have risen to the occasion, building furiously with a sense of mission. And in a year's time, if I had to take another visiting friend on the same outing, what would he think? Everything would be new and organized: would my friend realize at all that a quake had left a wake of destruction only two years ago? The author is an associate in a company that designs nature and culture travel, and offers consultancy in western China. (China Daily 04/29/2009 page9) |