|

OPINION> OP-ED CONTRIBUTORS

|

|

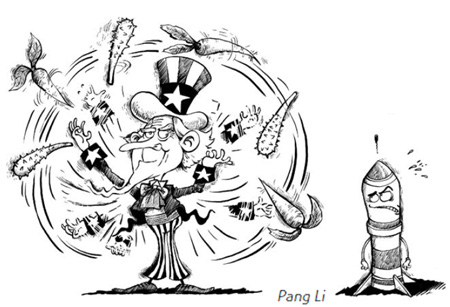

Resolve needed to resolve nuclear issue

By Sun Ru (China Daily)

Updated: 2009-10-30 08:08

Just a few days after a Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) official paid an unprecedented visit to the United States, Chinese President Hu Jintao met a delegation of the Workers' Party of DPRK in Beijing, saying Beijing-Pyongyang ties have reached a new level of goodwill. China has been trying to revive the Six-Party Talks to resolve the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue. Vice-Foreign Minister Wu Dawei's visit to the DPRK in August and State Councilor Dai Bingguo's in September were efforts in that direction.

And though Premier Wen Jiabao's visit to Pyongyang in early October was to commemorate 60 years of official ties with the DPRK, it helped in pushing forward China's agenda on the Six-Party Talks. China has been trying to push the DPRK and the US to return to the negotiations table. Now it's the responsibility of the US and the DPRK to take concrete steps to resolve the nuclear issue. But unfortunately they have not shown any clear sign of moving in that direction.

Though many experts think the first high-level official contact between the US and the DPRK in years could help resume the Six-Party Talks and set the process of denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula rolling, we should not expect Ri's visit to result in a major breakthrough. The reason is simple: Washington and Pyongyang policies indicate they are testing each other's patience rather than moving toward an agreement. For sure, the US is eager to take the process forward, but high-level, in-depth talks with the DPRK are not very high on its agenda. The US has been doing its utmost to devaluate bilateral contacts. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, and Special Representative for DPRK Policy Stephen Bosworth have defined bilateral contacts as a measure under the framework of the Six-Party Talks. Washington, in fact, has set a threshold for bilateral negotiations with Pyongyang, with Campbell saying the DPRK must fulfill all the agreements of the Six-Party Talks, including the joint statement issued on Sept 19, 2005. Plus, the US now prefers sanctions to bilateral contacts. Before the meeting between Ri and Kim, Clinton delivered a lecture at the US Institute of Peace, warning the DPRK in tough language that America would not lift the sanctions unless it adopted verifiable and irreversible means to end its nuclear program. On the very day Ri reached New York, the US Department of Treasury imposed sanctions on two of DPRK's commercial banks. The two key figures behind America's "carrot-and-stick" policy are Bosworth, the official in charge of contacts with the DPRK, and Philip Goldberg, a diplomat in charge of enforcing UN Resolution 1874. The Barack Obama administration is cautious in its dealings with Pyongyang because it still doubts its intentions. That's why bilateral contacts are only a means for the US to know how sincere the DPRK is. Since Pyongyang launched its satellite and conducted its second nuclear test, public opinion in the US has been overwhelmingly pessimistic about the DPRK giving up its nuclear program. So despite acknowledging the benefits of bilateral contacts, the Obama administration does not see them as yielding concrete results. Over the years, the US has become familiar with the DPRK's policy of first going on the offensive and then raising its bar at the negotiations table. Since the US has realized that changing the DPRK's policy is vital, it will not rise rashly to the bait again. In an interview with CBS during the US-Republic of Korea (ROK) summit in June, Obama said America would thwart the DPRK's move of getting benefits, such as food, fuel and loans, through belligerent behavior. "Belligerence and provocation" will not be rewarded, he said. The DPRK's intentions seem contradictory, for it is eager to advance bilateral contacts with the US, but not to return to the Six-Party Talks, let alone stop its nuclear program. Judging from the high-profile reception of former US president Bill Clinton in the DPRK and its proposal to sign a peace agreement with the US, it is apparent that Pyongyang wants to negotiate directly and exclusively with Washington. So in all likelihood, the DPRK's decision to return to the Six-Party Talks now depends on the outcome of Washington-Pyongyang meetings. The DPRK, it seems, believes that returning to the Six-Party Talks would not only hamper its economic and technological development, but also facilitate the end of its nuclear program. DPRK's top leader Kim Jong-il has promised Premier Wen Jiabao that a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula is Pyongyang's "set policy". But that promise has not been converted into action. Instead, Pyongyang has raised its bar again, by trying to link the Korean Peninsula nuclear issue with the normalization of relations with the US. The problem is that even if DPRK-US ties normalize, Pyongyang is not likely to give up its nuclear program completely. In fact, its second nuclear test gives the impression that it is actually preparing to strengthen its nuclear deterrence capability. The DPRK seems to be playing a dual game. On the one hand, it wants relations with the US to normalize. On the other hand, it has written a letter to the UN Security Council, saying its uranium enrichment process had entered the last stage, which means it still aims to upgrade its nuclear program. Since the UN passed Resolution 1874, the US has maintained contacts with China, ROK, Japan and Russia (the other four countries in the Six-Party Talks) to execute financial sanctions on and prevent nuclear and missile technology proliferation from the DPRK. The patient policies of the US (and the DPRK) may have eased tensions for now, but they are laden with dangers. Patience needs time. And the DPRK is likely to strengthen its nuclear capability with the passage of time, making the denuclearization process more difficult. Pyongyang, however, stands to gain little or nothing on the economic or security front if it doesn't give up its nuclear program and return to the Six-Party Talks. Hence, it's imperative that the US and the DPRK both show a sense of urgency in resolving the nuclear issue. It's time the US discussed with the DPRK its possible plans for denuclearization and offered it benefits if it went ahead with them, because neither will gain anything if Washington avoids sensitive issues at bilateral talks. The DPRK, on its part, should get over its illusions. It should not expect the US to transform the Six-Party Talks into disarmament negotiations, or to grant it the status of a nuclear power like India or Pakistan. In recent months, the DPRK has indicated to the ROK that it wants to improve relations. But Seoul has said that it is ready to do so only if Pyongyang promises to begin the denuclearization process. The ROK has dispatched humanitarian aid to the DPRK, though. This shows the DPRK is now less successful in its attempt to divide the other five parties in the talks. Moreover, with the Obama administration strengthening its ties with the ROK and Japan, the DPRK should not expect to get many concessions from it. So the only option the DPRK has been left with to get a favorable response from the international community is to take concrete steps to end its nuclear program. The author is a researcher with the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations. (China Daily 10/30/2009 page9) |

|||||||