-

-

China Daily E-paper

Op-Ed Contributors

Debate: Nuclear summit

(China Daily)

Updated: 2010-04-12 08:16

|

Large Medium Small |

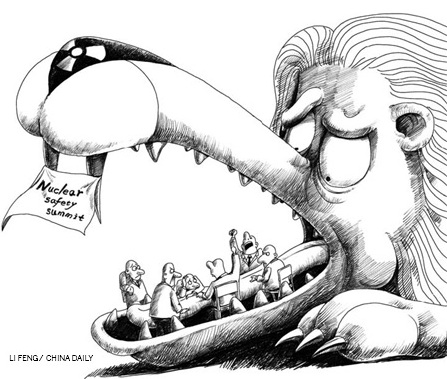

This week's nuclear security summit promises to address some of the most pressing issues facing the global community. What is at stake for its members? Two experts give us their views.

Li Hong: Agenda for the Obama administration

This week, the focus of the world media has turned to Washington for the nuclear security summit. With frequent interviews, special reports and comments inside and outside the US, President Barack Obama and his team have been delicately highlighting America's leadership in nuclear disarmament, non-proliferation and the fight against terrorism.

The purpose of the nuclear security summit is "a new international effort to secure all vulnerable nuclear material around the world within four years". But is it really a "new effort"?

If we look at the US proposals, initiatives and projects of the past two decades - that is after the end of the Cold War - we will see that the nuclear security issue has been on the table of every US president. The first US-initiated nuclear security program, the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program, started in 1992. Its intention was to secure nuclear weapons and materials in countries that were once part of the erstwhile Soviet Union and extend the protection of nuclear and radioactive materials across the globe. After 9/11, the US and other countries, led by the UN, are working closely and relentlessly to prevent nuclear weapons or technology from going into terrorists' hands.

It is true that such efforts are far from adequate and continuous global endeavor is needed to maintain safety in times of changing security environments. The international community already has an understanding on the issue and made concerted efforts to keep the world safe.

From form to substance, nothing is really "new" either for Americans or the rest of the world in this sense. But such skepticism may be too unfair to Obama. Something new could be found behind the scene if we study the US officials' speeches carefully.

First, a summit is being held in Washington to show Obama's vision and leadership in the fight against "nuclear terrorism". The summit will indicate America's return to multilateralism, too.

For the eight years that George W. Bush was US president, the disarmament movement did not experience anything but bitter hardship. The fight against terrorism has been severely distorted by US unilateralism and hegemony. International nonproliferation efforts were hampered because of regional nuclear issues, US double standards and selective approach to multilateral arms control treaties.

The international arms control process encountered obstacles on almost all fronts, for which the US was widely blamed. America's image had taken an unprecedented battering, dropping to a historical low. Obama has emphasized smart power diplomacy from the day he was sworn in US president. He has taken an important step toward multilateralism by convening the nuclear security summit. Even modest success of such a summit would be considered a big victory for Obama's foreign policy and his standing in American politics.

Second, a summit could strengthen America's image. After all, Obama won the Nobel Peace Prize by just delivering a speech on the concept of a nuclear-weapons-free world. The US has declared it "commitment to nuclear disarmament" by offering to destroy a part of the redundant nuclear arsenal and offered a "road map for reducing nuclear risks".

The nuclear security summit could prepare the way for the US to assume leadership of the 8th Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference, which is due soon. It is difficult to understand why the US gets the stamp of supreme moral leader in world nuclear disarmament. Probably it is because the world has long been used to its arbitrariness. What is important, however, is not which country is carrying the leadership banner but concrete steps to eradicate the nuclear threat. As the biggest nuclear power and the only power to have used nuclear weapons, the US has a special moral responsibility to ensure that such steps are taken.

Third, the nuclear security summit is a good forum for the US to contain the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) and Iran. Preventing nuclear material from falling into the hands of non-state actors is one of the most important purposes of the summit. Building a front line to block the DPRK and Iran from importing or exporting nuclear materials or technology, too, seems to be part of the summit's agenda.

The US has long been promoting the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which is focused on intercepting DPRK's and Iran's ships on suspicion of carrying nuclear weapons and materials. Obama said in Prague recently that the summit would "build on efforts to detect and intercept materials in transit and use financial tools to disrupt dangerous trade" by institutionalizing the existing mechanism including PSI.

PSI cannot be easily accepted by all the countries attending the summit because of the lack of an international legal basis. But the US would inevitably try to push for such interceptions of ships in the name of smashing illicit trade in nuclear materials and technology. It would not come as a surprise if the US makes full use of the opportunity at and beyond the summit to pressure other countries to join it on imposing new sanctions on Iran.

Joint international efforts to secure dangerous nuclear material have been long overdue, and the international community should unite to counter the nuclear threat.

The author is secretary-general of the China Arms Control and Disarmament Association.