Op-Ed Contributors

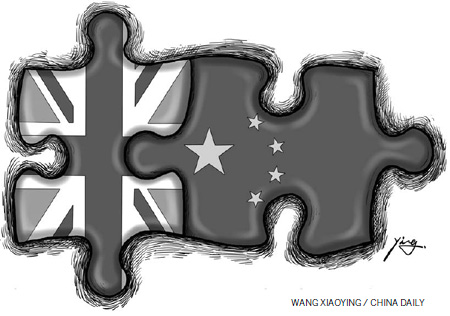

A boost to Sino-UK relations

By Tom Rafferty (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-11-10 07:54

|

Large Medium Small |

United Kingdom Prime Minister David Cameron is making his first official visit to China this week on his way to the G20 meeting in Seoul. He is accompanied by a large delegation of senior government ministers and business leaders.

The visit will be an early test for the foreign policy of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition that came to power after complicated post-election negotiations in May 2010. It will also give Beijing the opportunity to continue recent efforts aimed at deepening China's political and economic influence in Europe.

The Con-Lib coalition has committed itself to forging a "distinctive" foreign policy, which supplements Britain's traditional alliances with a more substantive engagement with developing economies such as India, China and Brazil. Cameron has already led a large trade mission to India and his intentions in coming to China are also commercial. Boosting inward investment and exports has been identified by the Con-Lib coalition as a key task for foreign policy, reflecting the priority given to reducing a national deficit that has grown to 12 percent of GDP.

China's leadership will be aware that Britain, like much of Europe, is going through a period of protracted economic strife. This is already having important strategic implications. The coalition government has outlined a controversial package of public spending cuts, which includes an 8 percent reduction in defense spending and a 24 percent cut to the Foreign Office's budget over the coming four years.

The gravity of the situation is such that Cameron has even managed to convince Euro-skeptics within the Conservative Party to accept a cost-sharing deal with France on nuclear and defense cooperation. In the future, the UK will be less able - and less willing - to practice the type of "liberal interventionist" foreign policy promoted by former prime minister Tony Blair.

Although evidence of the UK's shrinking strategic clout has been a source of concern for the United States, it may be viewed as an opportunity in Beijing. China offers Britain and Europe both the markets and sources of investment that they desperately need.

Recently, Beijing has launched a flurry of economic diplomacy, including a commitment to buy Greek (and, possibly, Portuguese) debt and a $22.8-billion trade deal with France.

Reaching an agreement with Cameron on increasing Chinese investment in the UK, from the paltry $44 million in 2009, and enhancing market access to British goods and services in China would mark another step in that direction. Britain is positioning itself as a gateway for external investment to Europe and as a liberal economic trading power with strengths in finance, law, science and education.

The primary motivation for Beijing to help kick-start Europe's moribund economy is that Chinese exports depend on the continued vitality of the European market. The European Union (EU) remains China's biggest trading partner. But Beijing will also be keenly aware that its economic power can enhance its political influence if it is deployed sensitively, possibly helping to deliver key global governance goals.

The recent agreement on reform of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) - in which European countries ceded two seats on the IMF board to enhance China's voting share - is one such example. The EU's weight within the G20 should not be underestimated, particularly with France assuming the chairmanship in 2011. Aligning with countries that are vehemently opposed to protectionism, like the UK, will help guard against a descent into a global "currency war".

In the broader context of growing tensions in Sino-US ties, China will also want to ensure that Europe does not bandwagon with America. Beijing will be encouraged by the divergences that appear to be opening up between the US and the EU over monetary policy. It is further helped by the fact that Europe does not have a clear stake in the strategic disputes that are fast emerging in East Asia.

Extending commercial and trade deals to European countries is potentially a means for China to develop a useful bulwark against increased US pressure.

Cameron would do well to recognize these dynamics during his visit to Beijing. Britain may be in economic difficulty, but that does not mean it is without leverage in its relations with China. Cameron is most likely to strike beneficial commercial agreements by making a forceful argument about the importance of China viewing its relations with the UK and Europe as an integral part of the global multilateral system. The interests of the UK and China are clearly complementary; if that can be recognized, the bilateral partnership can be an important force in confronting international challenges and reshaping the global order for the better.

The author is a visiting research fellow at Peking University's Center for International and Strategic Studies.

(China Daily 11/10/2010 page9)