Water, environment and development

The Aral Sea story and China's disappearing rivers are different symptoms of two important diseases: poor water management and focus on short-term economic benefits as opposed to the longer-term view of closely linking water with the environment.

The Aral Sea disaster should have been foreseen. Growing cotton, wheat and other crops in the perennial arid steppes by diverting the water of the two main rivers of the region can never be a sustainable proposition. Given the demise of the Aral Sea, the desert boom cannot be justified in economic, social or environmental terms.

Fortunately, we have also seen some cases of good understanding of the interrelationship between water and the environment. Much of Australia, for example, faced unprecedented droughts between April 1997 and March 2010. To tackle the serious water shortage over a prolonged period, the Australian government set up the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder, through the Water Act of 2007, to hold and manage water assets purchased from the water market or acquired as water savings from government-financed infrastructure upgrades. Its objective is to restore and protect environmental assets in the Murray-Darling Basin, which is spread over 1,059,000 sq km, an area slightly larger than the combined area of France and Germany.

By the end of March 2013, the new entity held water assets with a long-term average annual yield of more 1,100 giga-liters, equivalent to about 8 percent of the water previously available for consumption in the basin. During the past five years, the CEWH has delivered 2,250 giga-liters of water to the rivers, wetlands and flood plains in the Murray-Darling Basin. And this diversion of water has not harmed agricultural production in the basin because of efficient water management.

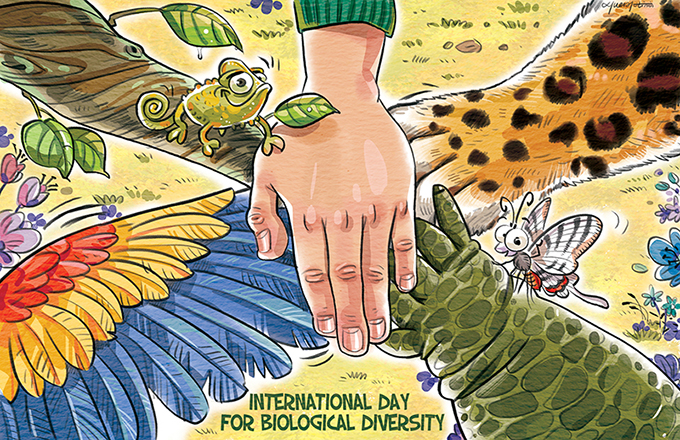

The benefits of this diversion have been substantial. It has helped sustain wetlands, and support native birds and plants through improved water quality, volume and duration of flows. It has improved fish breeding and the export of salt and nutrients out of the basin. It has also connected rivers, wetlands and floodplains to improve habitats for breeding and migration of animals and birds. Besides, it has improved the quality of water for irrigation and human use, and increased opportunities for tourism.

The Australian case shows we already have sufficient knowledge of the intricate interrelationship between water and the environment. We also know that the problems are solvable and we often have the means to solve them. What we lack is the political will and commitment to do so.

For at least the past 35 years we have known that the environment and development are two sides of the same coin. Development can never be sustainable unless environmental issues are given priority. Equally, the environment cannot be protected without development. Until and unless this symbiotic relationship is explicitly considered, we are unlikely to have sustainable development in any area, including water.

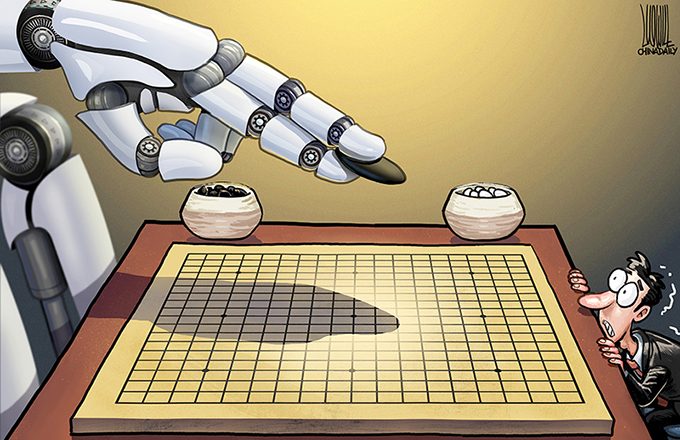

This consideration is especially important for a country like China, which has witnessed breakneck economic growth but has not laid enough emphasis on environmental protection. China faces the enormous challenge of combating existing air, water and soil pollution, and unless the trend is reversed, it will face even bigger environmental challenges in the coming years.

Peter Brabeck-Letmathe is the chairman of the board of Nestl S.A., Vevey, Switzerland, and the chairman of the 2030 Water Resources Group. Asit K. Biswas is a distinguished visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore, and founder of the Third World Centre for Water Management.

(China Daily 06/05/2013 page9)