Tough task for new WTO chief

The World Trade Organization begins a new chapter from Sept 1 with current director-general Pascal Lamy of France stepping down and Roberto Azevedo of Brazil assuming charge.

Azevedo will be the first Latin American director-general of the WTO. In fact, many have interpreted Azevedo's "election" as the head of the world's top trade body as a victory for developing countries. His closest contender for the job was Mexican nominee Herminio Blanco, who reportedly enjoyed the backing of the United States, the European Union, and other members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, including Japan and the Republic of Korea.

Azevedo's eventual selection reflects the rift between the developed and developing countries in shaping the WTO's agenda for global trade and also the clout that developing countries as a group now enjoy at the WTO.

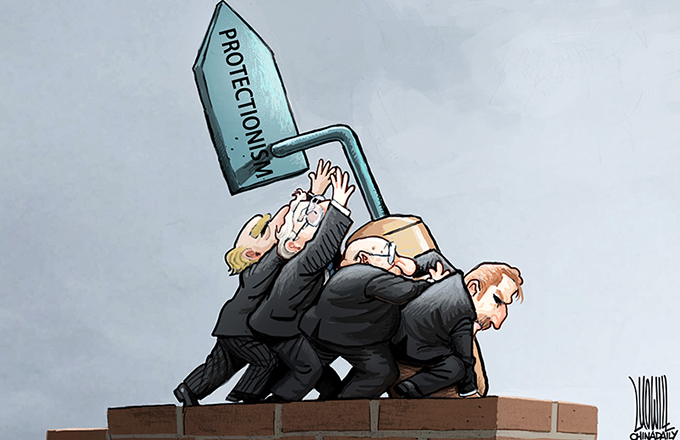

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development member states want the WTO agenda to stress on trade facilitation, government procurements, State-owned enterprise reforms, competition policy, intellectual property rights, labor standards and the environment. Developing countries are strongly sensitive to these issues, because acting on these "behind-the-border" issues involves introducing complex changes in domestic regulations.

While such changes will allow developed countries to gain greater access to developing economies' markets, particularly in sectors in which richer countries have greater comparative advantages like knowledge-based services, most developing countries will gain little by making new domestic regulations in these areas. As a result, the developing world has been reluctant to move on these issues and, with Azevedo as the director-general, it hopes the WTO will resist the efforts of OECD member states to pack the multilateral trade agenda in a manner of their choice.

Azevedo's selection reflects the strategic influence of developing countries on the WTO. But will developing countries be able to use this influence constructively to reshape the multilateral trade agenda? Developing countries as a group have not yet succeeded in creating a homogeneous alternative "non-OECD" vision for world trade. They have mostly ended up stalling negotiations at the WTO without suggesting other feasible options. This was especially evident during Lamy's tenure as WTO director-general.

So the biggest challenge for the new director-general will be to get the WTO discussions back on a constructive track, which will not be possible unless developed and developing economies agree to discuss the contentious issues constructively. Reaching such an agreement will be exceedingly difficult given the inherent mistrust between the developed and developing worlds, although Azevedo's choice of deputies shows he is keen on achieving this convergence.

His four deputies will be from the US, Germany, China and Nigeria. The choice not only underpins equal representation from the developed and developing worlds, but also symbolizes the most critical geo-political entities influencing modern trade.