Grasping Abe's real objective

The US pivot to Asia is struggling and China is growing steadily more convincing as a military power, which could oblige the Pentagon to seek the Chinese military's cooperation. Then there is the ROK, now generally acknowledged as a legitimate middle power, with President Park Guen-hye warmly received both in Washington and Beijing. And perhaps the newly nominated US ambassador to Japan, former US president John F. Kennedy's daughter Caroline Kennedy, is also an advocate of peace and trust.

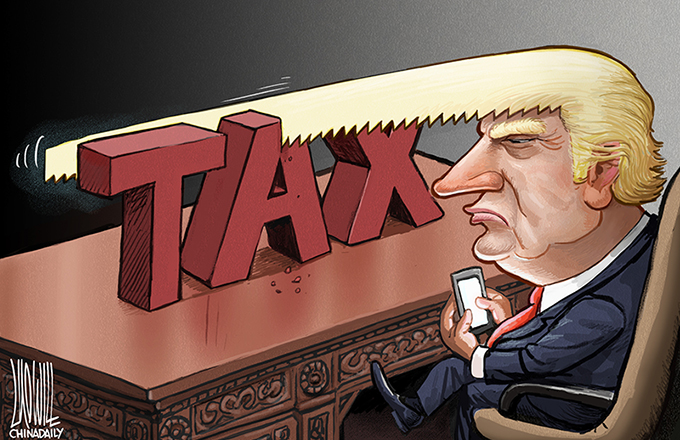

Under these circumstances, what choices has Abe's cabinet made? So far, it has seemed determined to upset Japan's neighbors and allies. The so-called Abenomics, Japan's new economic policy, appears designed not only to rejuvenate the Japanese economy after decades of stagnation, but also to boost defense spending to restore the strength and influence of the country's military.

Besides, Abe's government has adopted a hard-line stance on maritime disputes, especially against China, which has been equally assertive. The LDP is committed to amending Japan's pacifist constitution, too. And by using the excuse of defending against the missiles of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, it wants to allow Japan's Self-Defense Forces to conduct collective operations against external threats.

The US, in particular, finds Abe's shock therapy rather unwelcome. With its military shifting its focus to Asia and suffering serious constraints in its defense budget, the US is seeking strategic cooperative partnership with its allies, partners and like-minded countries in the region despite Abe's actions rocking the US boat.

Military-to-military contacts between the US and China are becoming warmer. Chinese Defense Minister Chang Wanquan has asked his US counterpart, Chuck Hagel, to make more efforts to responsibly manage regional instability. Chang also has urged the US to move toward rapprochement with the DPRK. All this has left Japan out in the cold.

Abe has devoted considerable time and energy to consolidate Japan's strategic partnership with Southeast Asian countries, in particular the Philippines and Vietnam, who share a common cause with Japan in resisting China's claims in the South China Sea.

Japan has extended its efforts to Australia and India, too, with Abe hoping to gain some leverage over China by getting involved in economic or political games. During the 1970s, after the Sino-Japanese rapprochement, and even in the early 2000s, the Chinese were dependent on a huge flow of Japanese foreign direct investment, but they will surely strive to avoid any repetition.

The ROK, too, has also moved on. Its options are no longer limited to a trilateral security cooperation with the US and Japan. And the Japanese contribution to this problem, Abe's investment in a "strong national defense", including Theater Ballistic Missile Defense, has not been appreciated by his neighbors.

Doubtless, the Japanese prime minister held some short bilateral meetings with other leaders at the G20 summit in St Petersburg, Russia, on Sept 5-6. When he met Obama, he may have complained of Japanese isolation and tried to seek greater US support. However, Obama may have told him to build bridges and promote trust with Japan's neighbors in the spirit of Obama's speech at the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr's famous "I have a dream" speech.

The author is senior research fellow at the Korea Institute for Maritime Strategy and visiting professor at Sejong University, Seoul.