COP21 meeting blog series one: we face the "last chance" again

By Bjorn Lomborg (China Daily) Updated: 2015-12-01 17:35

|

|

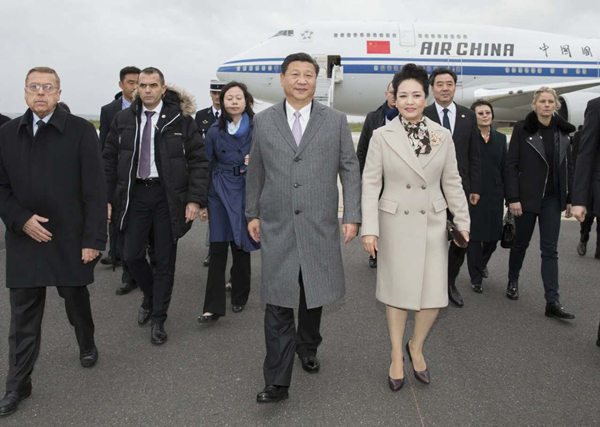

Chinese President Xi Jinping, accompanied by his wife Peng Liyuan, arrives in Paris, capital of France, to attend the opening ceremony of an international conference on climate change on November 29, 2015. [Photo/Xinhua] |

Déjà vu in Paris: 21st time lucky? Of course not

If you don't learn from history, you're bound to repeat it. Here in Saint-Denis, northern Paris, a history lesson is sorely needed.

Thousands are gathering for the 21st international global warming meeting. Hotels are already near-full, broadcasters are setting up, protestors are preparing to roar.

All because this summit is "the last chance" to avert dangerous temperature rises, if we listen to the Earth League or a bunch of others. It's going to be "too late" if a meaningful treaty isn't negotiated here in the next few days, says the French president.

It's a familiar script, though, isn't it? I remember people including then UK prime minister Gordon Brown all agreeing that the 2009 global warming meeting in Copenhagen was the world's very 'last chance'. "If we do not reach a deal," Brown went so far as to say, "no retrospective global agreement in some future period can undo that choice. By then it will be irretrievably too late."

Even by 2009, Brown was a late hanger-on to a crowded bandwagon. Doom-laden warnings about the 'last chance to save the planet' date as far back as the earliest climate summits, 20 years ago.

TIME Magazine declared 2001 "A Global Warming Treaty's Last Chance", and in 1989 the UNEP executive director warned that the planet faced an ecological disaster "as final as nuclear war" by the turn of the century.

Amid this alarmism, for 20 years well-intentioned climate negotiators have tried to do the same thing over and over again: negotiate a treaty that makes an impact on temperature rises. The result? Twenty years of failure with no significant effect on climate change.

These summits have failed for a pretty simple reason. Solar and wind power are still too expensive and inefficient to replace our reliance on fossil fuels. The Copenhagen-Paris approach requires us to force immature green technologies on the world even though they are not ready or competitive. That's hugely expensive and inefficient.

Thanks to campaigning NGOs, politicians and self-interested green energy companies which benefit from huge subsidies, many people believe that solar and wind energy are already major sources of energy. The reality is that even after two decades of climate talks, we get a meager 0.5 percent of our total global energy consumption from solar and wind energy, according to the leading authority, the International Energy Agency (IEA). And 25 years from now, even with a very optimistic scenario, envisioning everyone doing all that they promise in Paris, the IEA expects that we will get just 2.4 percent from solar and wind. That tells us that the innovation that's required to wean the planet off reliance on fossil fuel is not taking place.

Instead of hoping that the experiment will succeed at the 21st attempt, the leaders gathering here this week should change course and invest a lot more in research and development of green energy technology. If we could innovate down the price of green energy so it could genuinely compete in the market, everyone would be interested in a transition away from fossil fuels.

Over the next two weeks, I will report from Paris on developments. I am sure we will hear nice speeches and grand promises. There will be all the usual political intrigue and drama. Anything could happen. But I can tell you one thing for sure right now: history suggests this "last chance" will unfortunately come and go with no real impact on temperature rises.

Dr. Bjorn Lomborg is director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center and Visiting Professor at Copenhagen Business School. He researches the smartest ways to help the world, for which he was named one of Foreign Policy's Top 100 Global Thinkers. His numerous books include The Skeptical Environmentalist, Cool It, How to Spend $75 Billion to Make the World a Better Place and The Nobel Laureates' Guide to the Smartest Targets for the World 2016-2030.