Unlocking the potential of Chinese cities

|

| SHI YU/CHINA DAILY |

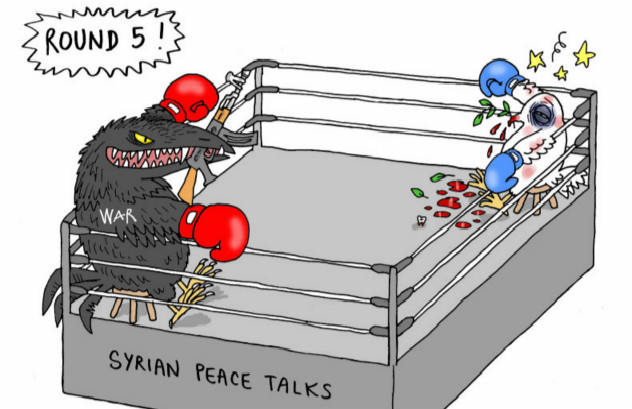

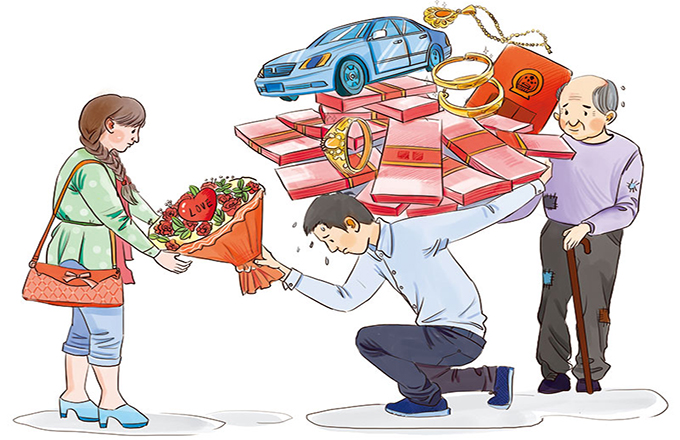

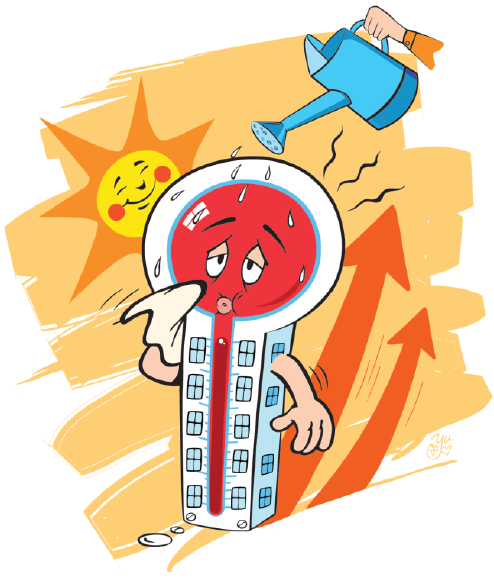

Of course, the housing situation is most urgent in the first-tier cities. And their governments have moved quickly to cool the market.

But this is just a temporary fix. A longer-term solution will require the authorities to address the fact that demand for a limited supply of residential property is high and rising, owing to the rapid flow of often young Chinese talent to cities that offer access to economic opportunities, not to mention better public infrastructure. Policymakers must determine the proper balance between State control and market forces in guiding urbanization throughout the country.

As it stands, urbanization pressure is being felt by the top 100 (out of 600) Chinese cities that are home to 714.3 million residents-52.8 percent of the total population-and generated 75.7 percent of China's GDP in 2016. Six of those 100 cities recorded GDP growth above 10 percent last year, compared with the national average of 6.7 percent; 82 recorded GDP growth between 6.7 percent and 10 percent; and just 12 grew by 6.7 percent or less.

Perhaps more significant, per capita GDP in 33 Chinese cities is higher than $12,475, meaning that, by World Bank standards, they have attained high-income status. Four years ago, only 16 Chinese cities had crossed that threshold. Urbanization in these high-income cities may provide more valuable insight into how to continue China's remarkable development story than the experiences of the first-tier cities.

A new book, China's Evolving Growth Model:

The Story of Foshan (co-authored by one of us), offers a case study of one of those cities. In recent years, Foshan has transformed itself from a rural county outside Guangzhou, capital of South China's Guangdong province, into the most dynamic industrial city in China with per capita income reaching $17,202 in 2016, compared with $16,624 for Beijing and $16,251 for Shanghai. In 2015, Foshan's GDP grew by 8.3 percent, compared with 6.7 percent in Beijing and 6.8 percent in Shanghai, with industry accounting for 60 percent of the city's GDP.

Moreover, in a country where excessive debt is a growing concern, Foshan's loan-to-GDP ratio in 2011 was only 85 percent-far less than the national average of 121 percent. Foshan's rapid GDP growth was driven by the private sector, with appropriate local government support, and therefore depended largely on self-financing, not debt. Likewise, the private sector has financed about two-thirds of Foshan's fixed investment, which runs up to 30-40 percent of GDP.

Foshan's development strategy focused on embedding the city within the supply chains of the dynamic Pearl River Delta-which includes the global cities of Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou-thereby securing linkages to the entire world. It also included the development of skills and capacity in specialized sectors, creating the world's largest lighting and furniture markets in the world.

Foshan now boasts numerous private companies and small and medium-sized enterprises spread across its more than 30 specialized industrial clusters and integrated into global supply chains.

The key to success has been the authorities' flexible approach, guided by close monitoring of market signals. Thanks to such monitoring, Foshan's municipal- and county-level governments recognized a dramatic restructuring in global supply chains and responded accordingly, such as by improving housing and healthcare, providing such social services even to migrant labor, and addressing excessive pollution.

As Foshan has proved, cities have a unique capacity to support growth-including by fostering competition, advancing innovation, and phasing out obsolete industries-while addressing social challenges, tackling pollution, and creating a labor force that can cope with technological disruption. As China attempts to manage urbanization-responding to, rather than attempting to overpower, market forces-the Foshan model may well prove invaluable.

Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the UNEP Advisory Council on Sustainable Finance. Xiao Geng, president of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Project Syndicate

- The future of sustainable urbanization in China

- Cities vie for opportunities in new urbanization blueprint

- China’s Transportation Infrastructure Construction on Urbanization Drive: Impacts and Policy Options(No.13, 2017)

- Urbanization requires market-based planning

- Successful urbanization not just homebuying

- People-oriented urbanization