Improve talent evaluation, check brain drain

|

|

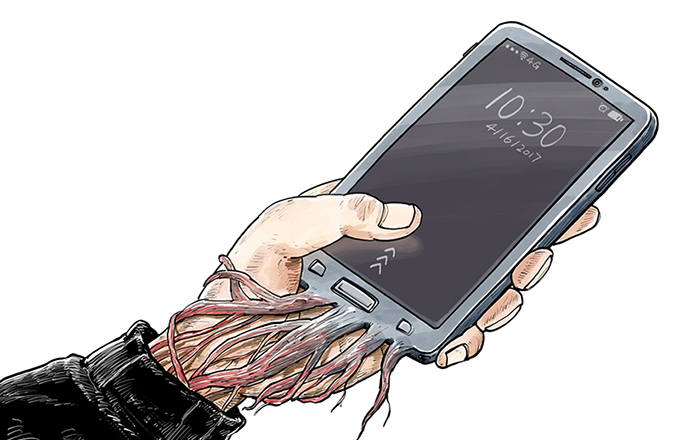

ZHAI HAIJUN/CHINA DAILY |

Some recent media reports said a Chinese youth, whose family spent about 4 million yuan ($581,000) on his education in the United States over eight years, returned home only to realize he might not be able to earn that amount back because it was not easy for him to find a well-paying job.

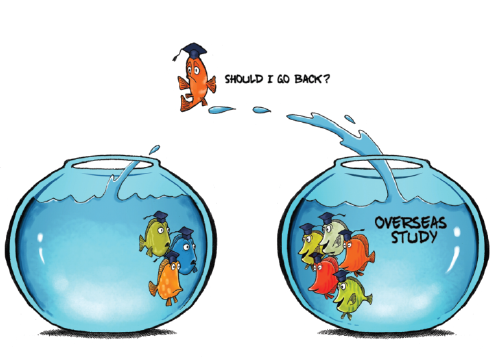

So, is studying abroad still a worthwhile option for Chinese youths?

The answer differs from person to person, because to study abroad is a personal choice, and entails rational planning.

But education is more than just about economic returns. Education authorities must recognize this fact before reaching a conclusion from the above example (and similar cases) that China's brain drain can be checked.

Many Chinese families send their children to study abroad because they care more about the quality of education in developed countries than economic returns, even though the latter is also important.

Therefore, if China wants to check the outflow of young talents-let alone attract talents from abroad to its schools-it should first intensify reforms to improve the quality of education in the country.

Statistics show that from the late 1970s, when China launched its reform and opening-up, to last year, about 4.58 million Chinese went to study abroad, and 3.22 million of them returned home.

But despite the high percentage of returnees, the "outflow" of students continues to intensify. According to the Ministry of Education, 545,000 Chinese went abroad to study in 2016, up 36.26 percent compared with the figure in 2012, with about 70 percent of them seeking bachelor's, master's or doctoral degrees.

More students are returning from abroad mainly because of their falling academic and practical knowledge.

Ten years ago, most Chinese youths went abroad, mostly to developed countries, to seek college degrees, especially postgraduate degrees, and many of them chose to stay after graduation because the job market there could absorb them.

Nowadays, however, many Chinese students studying abroad are actually not "qualified"; they seek overseas degrees because their families "buy" them seats in cash-thirsty schools. No wonder it is difficult for such youths to find good jobs abroad or, after they return home, in China.

Official data show that 87 percent of the science and engineering graduates, talents that China needs the most, stay abroad, making China the largest "brain" exporter in the world.

In other words, real talents make up only a very small percentage of the returnees. And the high number of students returning from abroad does not necessarily mean that education, careers and the business environment in China have become more attractive compared with developed countries. So, one should not conclude that studying abroad is no longer worth it.

Good students still have a strong desire to pursue the best education in the world. In contrast, some wealthy families don't care whether their children are eligible to study abroad because they have the money to spare and want their children to just have the overseas study experience. But such graduates cannot win the recognition of the market or society.

Treating people according to their "identity", instead of their knowledge and capability, is an outdated concept. Some second-rate graduates from top universities in China may not be even half as good as an average graduate from an average school for the job market.

The education authorities must realize that even if studying abroad does not translate into good jobs at home, many Chinese parents are still willing to send their children overseas for higher education.

The outdated talent evaluation system and not-so-perfect quality of education in China are prompting parents to send their children to study abroad. And until the quality of education is improved and the academic environment changed, the brain drain will continue.

The author is a columnist for Beijing Youth Daily. The article was first published in the newspaper on April 19.