Restoring competition in digital economy

The digital economy is carving out new divides between capital and labor, by allowing one company, or a small number of companies, to capture an increasingly large market share. With "superstar" companies operating globally, and dominating markets in multiple countries simultaneously, market concentration in G20 economies has increased considerably in the past 15 years.

To address this phenomenon, that is, to restore competition and reduce income inequality between capital and labor, the G20 should create a "World Competition Network". As a larger share of total income shifts to capital across many G20 countries, the World Competition Network would seek to reverse the decline in labor's share of GDP.

For a period after World War II, 70 percent of national GDP accounted for labor income, with the rest being capital income. John Maynard Keynes described the stability of the labor share as something of a "miracle". But the rule has since broken down. Between the mid-1980s and today, labor's share of world GDP declined to 58 percent, while that of capital rose to 42 percent.

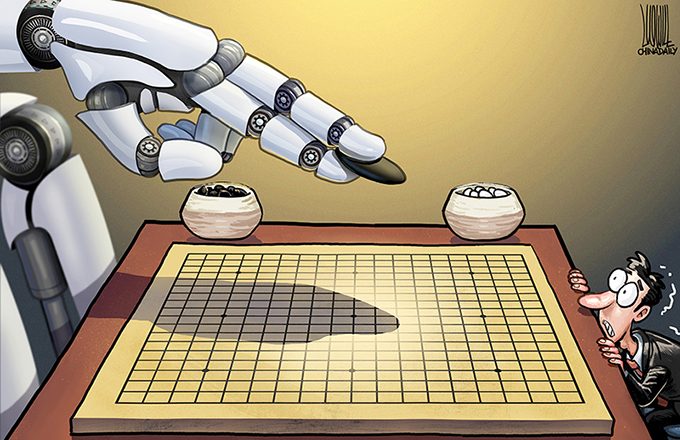

Two forces in today's digital economy are driving the global decline in labor's share of total income. The first is digital technology itself, which is generally biased toward capital. Advances in robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning have accelerated the rate at which automation is displacing workers.

The second force is the digital economy's "winner-takes-most" markets, which give dominant companies excessive power to raise prices without losing many customers. Today's superstar companies owe their privileged position to digital technology's network effects, whereby a product becomes even more desirable as more people use it. The digital economy has given rise to large companies that have a reduced need for labor. And, once these companies are established and dominate their chosen market, the new economy allows them to pursue anti-competitive measures that prevent actual and potential rivals from challenging their position. And, as economists David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen show, the US industries with the fastest-growing market concentration have also seen the largest drop in labor's share of income.

This increased market concentration is widening the gap between the companies that own the robots (capital) and the workers whom the robots are replacing (labor). But confronting it will require us to reinvent antitrust for the digital age. As it stands, national competition authorities in the G20 economies are inadequately equipped to regulate corporations that operate globally.

Moreover, the G20 cannot simply trust that global competition will correct on its own the tendency toward increased market concentration. As Andrew Bernard has shown for the United States and Thierry Mayer and Gianmarco Ottaviano have demonstrated for Europe, international trade favors large superstar companies. Indeed, globalization may provide advantages to the largest and most productive companies in each industry, causing them to expand-and forcing smaller and less-productive companies to exit. As a result, industries become increasingly dominated by superstar companies with a low share of labor in value added.

The US is a case in point. It is host to many of today's superstar companies, and yet US antitrust regulators have not been able to restrain those companies' market power. As the G20 looks for ways to address the problem of market concentration, it should take lessons from the US experience, and look for ways to improve upon the US' failures.

Rather than starting from scratch, we will need to build on national-level competition authorities' institutional knowledge, and include experienced personnel in the process. The European Competition Network can serve as a blueprint for a G20-level network.

The objective of a world competition network is to build an effective legal framework to enforce competition law against companies engaging in cross-border business practices that restrict competition. The network may coordinate investigations and enforcement decisions and develop new guidelines for how to monitor market power and collusive practices in a digital economy.

In the past, the G20 has focused on ensuring that multinational companies are not able to take advantage of jurisdictional differences to avoid paying taxes. But the G20 now needs to expand its scope, by recognizing that digital technologies are creating market outcomes that, if unchecked by a new World Competition Network, will continue to favor multinational companies at the expense of workers.

The author is chair of international economics at the University of Munich and a senior research fellow at Breugel, the Brussels-based economic think tank.

Project Syndicate