First half growth marked by deleveraging

|

|

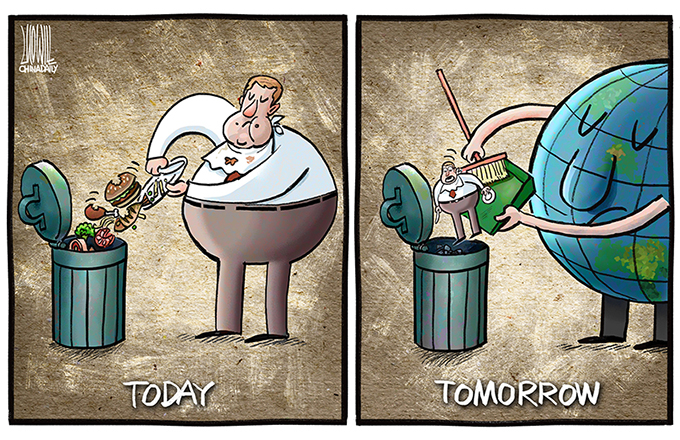

SHI YU/CHINA DAILY |

In May, Moody's Investor Service downgraded China's credit rating. But it took less than a day for China's financial markets to recover from the downgrade. Recently, index giant MSCI announced the partial inclusion of China-traded A shares in the MSCI Emerging Market Index, a move which was seen as overdue in the mainland because China is under-represented in global equity indexes relative to its economic influence. The inclusion is thus predicated on a long and gradual move.

In brief, Moody's believes the rapid rise of Chinese debt has potential to degrade its future prospects, while MSCI thinks China's future is grossly undervalued. The first focuses on the cyclical story; the second on the secular potential.

There is a reason for the seemingly mixed messages: Like advanced economies, China has now a debt challenge. Yet the context is different and so are the implications.

In 2015, the United States' total debt (private non-financial debt plus government debt) exceeded 251 percent of the economy. Except for Germany (166 percent), the comparable figures in other major European economies, including the United Kingdom (249 percent), France (278 percent) and Italy (253 percent), are similar to that of the US. In Japan, total debt exceeds a whopping 415 percent of GDP. In China, it was 221 percent but it has grown very rapidly.

The numbers illustrate the stakes, but not the story. In advanced economies, total debt has accrued over the past half a century, decades following industrialization. After rapid acceleration amid industrialization and the move to post-industrial society, their growth has decelerated, along with excessive debt burden in the postwar era.

The advanced economies' debt is the result of high living standards that are no longer fueled by catch-up growth and are not adequately backed up by productivity, innovation and growth. So living standards are sustained with leverage.

In China, total debt accrued in the past decade amid industrialization. Unlike advanced economies, different regions in China are still coping with different degrees of industrialization. As the urbanization rate is about 56 percent, intensive urbanization will continue for another decade or two.

Due to differences in economic development, living standards in China remain significantly lower relative to advanced economies. Yet rising living standards, which the central government hopes to double by 2020, are fueled by catch-up growth and supported by productivity, innovation and growth.

In advanced economies, debt is a secular burden; in China, it is cyclical side effect. In both, left unmanaged, it has potential to undermine the future.

But why did Chinese debt rise so rapidly? Even in 2008, it was 132 percent. Only a tenth was central government debt (17 percent), and most involved private debt (115 percent). In 2015, government debt was about the same (16 percent), but private debt had soared (205 percent).

The dramatic increase can be attributed to two surges. The first is the result of the massive $585 billion stimulus package of 2009, which contributed to new infrastructure in China and to global growth prospects. But the huge amount of liquidity it unleashed for speculation is today reflected in excessive local government debt (included in private non-financial debt data).

Another sharp surge followed last year, which saw a huge credit expansion as banks extended a record $1.8 trillion of loans. It was driven by robust mortgage growth, despite government measures to cool housing prices. As a result, credit was growing twice as fast as the growth rate.

But since late last year, the cyclical story has been shifting. For years, policymakers have advocated tougher measures against leverage. Concurrently, global pressures have increased with the US Federal Reserve's rate hikes.

The big news is that deleveraging has already begun. Late last year, China's central bank adopted a tighter monetary stance and has increased tightening this year. In May, according to Reuters, the total social financing amount fell to $156 billion from $200 billion, much more than analysts expected. As the decline was driven by non-bank financing, broad M2 money supply expanded by less than 10 percent on a year-to-year basis, the weakest pace in two decades.

For now, policymakers' deleveraging is on track, as long as it does not downgrade the growth target. In China, it is a medium-term project. In advanced economies, deleveraging is likely to take far longer. But they will not succeed without structural reforms-just as China is already executing reforms to rebalance the economy toward consumption and innovation.

The author is the founder of Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (USA) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Centre (Singapore).