With US out of Paris treaty, can we revisit Kyoto?

|

|

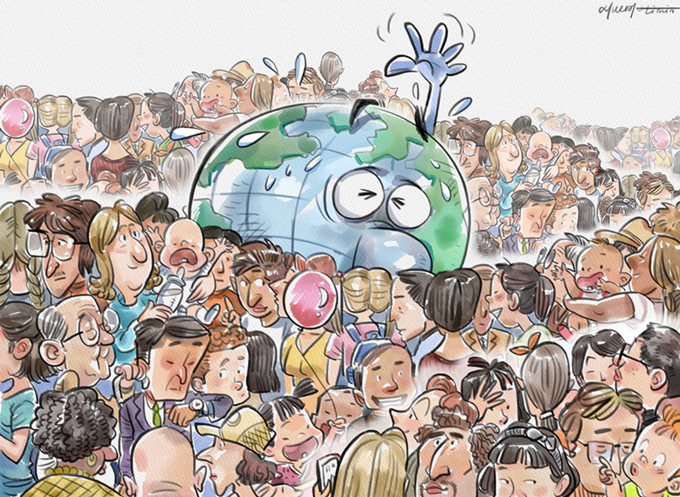

CAI MENG/CHINA DAILY |

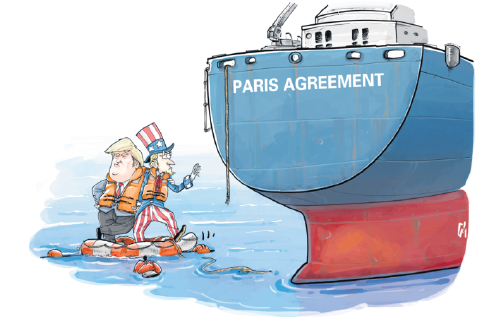

US President Donald Trump pulled his country out of the Paris climate change agreement last month. His move generated a lot of heat in political, diplomatic and media circles-and most of the reactions were extremely critical. Trump's international isolation was obvious then and became almost physically evident at the just-concluded G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany.

The Paris Agreement is not binding; in other words, it contains commitments on emission cuts and, mostly on the part of developed nations, funding for developing or less developed countries meant to facilitate access to green technologies, which should be undertaken on a voluntary basis.

Besides, the Paris Agreement does not fully honor the Kyoto Protocol and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which enshrined two important principles in global climate negotiations: historic responsibility (and related to it the idea of emission space for developing and less developed countries) and the idea that developed countries had to undertake binding obligations.

After years of post-Copenhagen negotiations, the international community agreed to junk these fundamental principles to get the United States on board. And Trump has made a mockery of that compromise.

Several propositions follow logically. The first is that the targets envisaged under the Paris climate deal cannot be met without the active participation of the US.

Some US states, like California, and some US corporations have promised to formulate targets and meet them; some will enter into separate agreements with relevant (perhaps UN-mandated) authorities to pursue this end. These states and corporations could also contribute to the corpus intended to help poorer countries to follow a cleaner growth track. Still, without the participation of the US in its entirety, the Paris targets cannot be met.

No amount of effort by other countries to take up the slack will be enough if Trump does not reconsider his ill-considered decision. And the G20 summit provided enough evidence that Trump has no intention of backing down. This evidence came in connection to the question on the use of fossil fuels, which are largely responsible for the emission of greenhouse gases. The US, however, has said it would work with other countries toward cleaner and more efficient use of these fuels, without committing any time frame for phasing them out. And this is just one of the many promises made by the US which it cannot be expected to honor.

Some of the more optimistic observers have noted that even though Trump has decided to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement, the procedures specified in the deal will make it impossible for the US to exit before late 2020, by which time the next US presidential elections will have been held.

But what Trump can do and, in fact, has already started doing is ignore the Paris Agreement, because the commitments made under it are voluntary and, therefore, not binding. The US can ratchet up its use of fossil fuels in an attempt to re-industrialize its so-called rust belt (whether or not that is a plausible strategy), it can step up prospecting for oil or shale and it can emit as much greenhouse gases as it wants, while nominally still being a part of the Paris Agreement.

So apart from increased emissions, we should not be surprised if the US' contributions under the Paris Agreement falls to zero or very close to it-that's what Trump has promised and has been indicated by the general budgetary drift, which includes drastic cuts in foreign aid and allotments to the office of the secretary of state.

All of this adds up to the inescapable fact that any concerted global action against climate change must be designed and undertaken factoring out the US at least for the next four years or so. This conjuncture, then, affords us a very real opportunity to ask a very important question: With the US, unfortunately, out of the way, should the international community, led by China and India, revisit the basic principles underlying the Kyoto Protocol-common but differentiated responsibilities, historic liabilities, binding obligations?

The author is a senior journalist and independent researcher based in India.