Digital dividend to boost economy

Over the past four decades, China has gone from being a low-wage supplier to one of the three most important links in the global value chain, alongside the United States and Germany. Despite growing concerns about China's corporate debt and its ability to escape the middle-income trap, rapid digitization will allow the Chinese economy to continue moving up the value chain.

Following its strategic "opening up" almost 40 years ago, China provided an abundant source of cheap land and labor, which enabled it to achieve economies of scale in consumer manufacturing. Then, as China moved toward middle-income status, it became a major consumer market in itself.

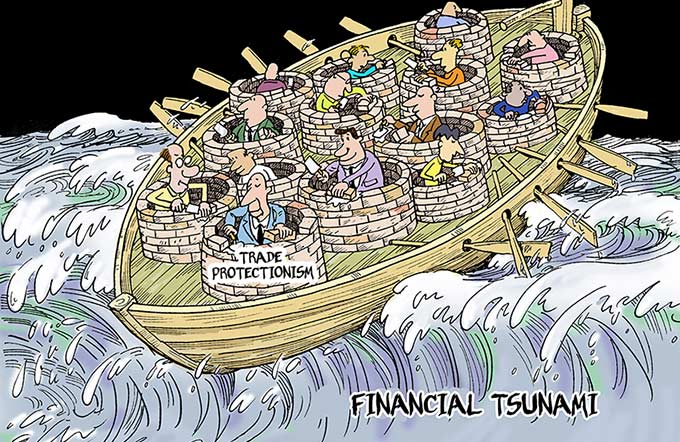

In 2012, China's current leaders recognized that the country's "demographic dividend" had run its course: the Chinese economy was reaching its "Lewis turning point", the stage at which its surplus labor supply would be exhausted, and wages would start to rise. At the same time, the "opening-up dividend" was also reaching maturity, and encountering protectionist barriers around the world.

China can still tap new markets through efforts such as the Belt and Road Initiative. Ultimately, sustaining rapid growth requires continuing to move up the global value chain, by implementing further economic reforms and focusing on new technologies.

China's 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20) reflected its commitment to market allocation of resources and lowering the costs of doing business. In 2015, the authorities' "Made in China 2025" and "Internet Plus" initiatives signaled a determination to take the country's manufacturing base into the internet age. Together, the two plans aim to integrate artificial intelligence, robotics, and social media into manufacturing processes, and to digitize China's economy and society.

Since 2015, China has taken the lead in e-commerce worldwide, with online purchases accounting for 18 percent of total retail sales, compared with just 8 percent in the US. Moreover, according to iResearch, mobile payments in China already amount to $5.5 trillion, roughly 50 times that of the US. In most Chinese cities, electronic-wallet apps on mobile phones are replacing cash as the primary mode of payment.

China's leap into the digital age was facilitated by a combination of physical and digital technologies and new business models. And, by streamlining the exchange of information and facilitating coordination of complex tasks, the Chinese social media app WeChat-with 938 million users as of the first quarter of 2017-has contributed to previously unimaginable productivity gains.

According to the Boston Consulting Group, Chinese e-commerce platforms' business models have evolved differently from those in the West, as they have responded to Chinese consumers' rapidly increasing spending power and enthusiasm for innovation.

Having been encouraged by the government to experiment with internet-based business models, Chinese companies are upending traditional practices. And this is happening so quickly that even the government now feels pressure to catch up, by adopting new technologies such as blockchain and AI.

E-payments are a key factor in lowering business and transaction costs in China, because they improve efficiency in the retail sector, where prices can still be higher than in the US even when the products are made in China. But the emergence of fraud and the failures of some peer-to-peer platforms point to the need for tighter regulations to maintain systemic stability.

As more activities become digitized, China's integration into the global value chain will increasingly occur in digital spaces. Chinese producers can use 3D printing, robotization, and big data and AI applications at the local level, while still tapping into global markets and sourcing ideas and skills from abroad. There are now endless possibilities for dividing production and consumption into separate stages.

Indeed, Chinese policymakers will have to confront various "digital dilemmas" in the coming years. As in a game of go, China's leaders need to move the country's pieces-that is to say, effect change in the SOEs' business models-in the right place, at the right time, and in a coordinated fashion.

SOE managers can credibly argue that heavy regulations place them at a competitive disadvantage, and that the technology giants are eating their lunch by free-riding on State-administered telecommunication, transportation and financial channels. The technology giants, meanwhile, argue that if they could just move faster into inefficient production and distribution areas, not least mobile payments, productivity growth would accelerate.

Another dilemma is that digitization is good for consumers, but possibly bad for employment and social stability. In a "Digital China", there will necessarily be winners and losers. But the sooner displaced workers can adapt to new realities, the healthier the system will be.

Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the UNEP Advisory Council on Sustainable Finance, and Xiao Geng, president of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor at the University of Hong Kong. Project Syndicate