A technician shows how to reprint an ancient publication at an exhibition running at the National Library. Wu Changqing

For classics expert Li Zhizhong, it was a once-in-a-lifetime discovery. While traveling around the country in search of texts for China's first National Classics Treasures List last year, Li found 97 books printed in the Liao Dynasty (916-1125).

Such books are very rare because the Khitan rulers of Liao strictly prohibited books from leaving its border and very few books printed in the Khitan language survived the wars against the Northern Song (960-1127), the Jin (1115-1234) and the Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties.

Most of the Liao Dynasty books were discovered in 1974 in a 1,000-year-old wooden pagoda in Yingxian county, Shanxi province. However, their historical value had been overlooked until Li came across them last year. He immediately included them in the national list.

"Few classics scholars are lucky enough to see so many Liao books in a lifetime," says Li, who worked for 40 years in the National Library. "The books fill in many empty holes in the history of Liao and clear away doubts in studies on ancient publication."

Regarded as a vital tool in preserving the essence of Chinese culture, the classics have gained unprecedented attention from both society and the government over the past few years.

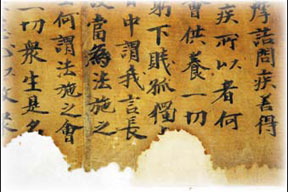

A Tang Dynasty scroll, valued at 1 million yuan ($145,800), is now preserved at the National Library. Gao Erqiang

Last year, a nationwide survey was launched to identify and prioritize classics in need of protection. On March 1 this year, the government issued the first National Classics Treasures List, which included 2,392 items of utmost value. Also announced were 51 units protecting these classic works.

Li Zhizhong has been instrumental in realizing this survey. A member of the People's Political Consultative Conference, he made a proposal in 2006, calling for more funding and better protection for the classics.

About a year later, the State Council issued Suggestions on Further Strengthening the Protection of Classic Works. Li was named head of a 66-member panel to oversee the work, while 57 organizations, such as the National Library, the Palace Museum and the Peking University Museum, joined in conducting the survey.

In their trips around the country, Li and other experts appraised more than 5,000 books from libraries, museums, temples and private collections. The initial list includes 2,282 classics in Chinese and another 110 classics in 14 ethnic minority languages or ancient tongues that are no longer in use. The survey is expected to continue for another three or four years, during which more classics will be added to the list.

Once the classics are identified, experts will set up better storage facilities, digitize the rare books and train personnel to preserve them, Li says.

Of all the libraries in China, the National Library has the best storage facilities for classic works.

The Library's collection includes the Dunhuang scrolls, one of China's most prized classics, which recently have been installed in a new, 240-sq-m storage room. After being stored for centuries in a dusty cave in the Dunhuang Mogao Grottos, the scrolls are secured in a climate-controlled underground sanctuary at the Library.

The scrolls are housed in 144 elaborate cupboards made of nanmu, a precious wood, according to Zhang Ping, an expert with the library's Rare Books Restoration Center, who helped design the cupboards.

Each scroll is kept in a box with nanmu on the cover and camphor wood on the sides and bottom, to fend off insects. The scrolls are mounted on wooden bars, to prevent damage to the fragile paper; broken pieces of the scrolls are also kept in special containers.

Besides physically restoring the classics, efforts have been made to digitize them, so more people can have access to the precious knowledge.

For the past 20 years, the National Library has been cataloging its rare books and putting them on microfilm. Chinese and international researchers have joined hands in re-creating the virtual Mogao Grottoes online at idp.bl.uk and its Chinese equivalent, idp.nlc.gov.cn.

Another bigger, national initiative involving more books was launched in 2002, when the Ministries of Culture and Finance joined hands in the Chinese Rare Books Reconstruction Project.

Some 700 rare books dating before the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) have been reprinted. Complete sets of the reprints, which costs some 3 million yuan ($430,000) each set, are stored in 100 provincial and university libraries, so students and common readers can easily browse through them, without going through complicated procedures that are necessary if they want to see the original classics.

To supervise the protection work, the National Rare Books Protection Center was set up a year ago in the National Library. Chen Hongyan, the center's vice-director, says the center's main tasks are carrying out the survey of classics, coordinating other rare books protection centers at provincial and lower levels and training professionals in the field.

There are less than 200 professionals in China qualified in verifying and restoring classics, which has seriously hindered the protection of the classics, Chen says.

The center has held several training sessions with the National Library, the Peking University and other organizations to offer courses on appraising and repairing classics. An education system from vocational schools to undergraduate and postgraduate studies is taking shape.

At the National Library's Rare Books Restoration Center, three students in their early 20s are taking an internship under the guidance of the center's 30 formal members, who are the leading experts in repairing old books.

The interns, who come from Nanjing Mochou Secondary Technical School in Jiangsu province, cannot get a formal job at the National Library because they don't have a university degree, says Zhang Ping.

In an online discussion in May, Vice Cultural Minister Zhou Heping promised Internet users that the government would reform the present personnel system to include talents from different disciplines.

"We all came from other trades and learned from the old masters," says Zhang Ping, who worked as a carpenter 20 years ago. "It's wonderful to see young people from different, scientific fields joining our work. They are the hope of our profession."

(China Daily 09/02/2008 page19)