|

|

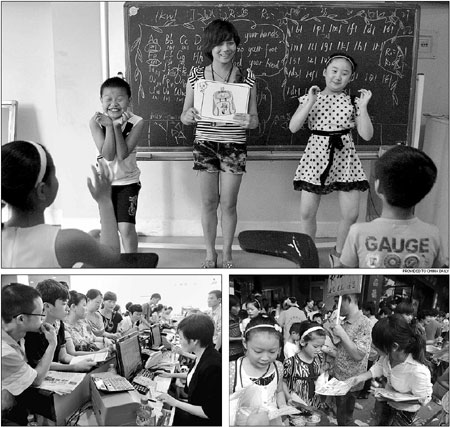

Top: Children at an English class at a training institute in Wenling, Zhejiang province. Left: Parents help their children apply for English classes at a private educational establishment in Guiyang, capital of Guizhou province. Right: Training institute staff members deliver ads for post-school courses to students in Fuyang, Anhui province. Provided to China Daily, Wu Dongjun / for China Daily, Hei Bai / for China Daily

|

Overhaul urgently needed for chaotic private education market, reports Yang Yang.

When Zhang Yusi began looking for an English-language course in preparation for study overseas, she felt overwhelmed by the huge number of advertisements for numerous service providers, who trumpeted their strengths in the media and on street billboards.

After some deliberation, the 24-year-old graduate student at Beijing's Central Academy of Drama opted for big-name establishments, but was then deterred by the high tuition fees for several months of intensive study.

The large number of unflattering comments on the Internet, posted by former students who regretted having been taken in by ads and promotions, also gave her cause for concern.

So, after weeks of bargaining, Zhang was surprised to learn that Wall Street English, one of China's best-known language-training schools, was offering a yearlong course at a nonrefundable, promotional price of 25,000 yuan ($4,100), far lower than the company's usual 40,000 yuan fee.

Welcome to the chaotic, but highly lucrative, world of China's private education industry.

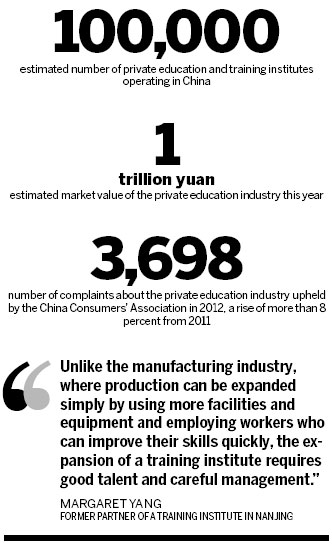

Industry insiders estimate that at least 100,000 private educational and training institutes are operating in China.

The real number may be much higher, because many providers have registered with the State Administration for Industry and Commerce as education consultancies.

Theoretically, these consultancies are not allowed to provide education or training because they don't satisfy the strict rules laid down by the Ministry of Education.

In reality, the rules haven't stopped unauthorized players from entering the industry, whose market value rose to 960 billion yuan in 2012 from 760 billion yuan in 2010, according to a blue paper published jointly by the 21st Century Education Research Institute and the Social Science Academic Press under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. It further estimated that the market will surpass 1 trillion yuan this year.

As the market has become increasingly crowded, the industry has been plagued by a raft of problems, including promotions and ads that misrepresent the educational backgrounds and teaching strengths of faculty members, exorbitant prices, courses and schedules that are changed without prior notice, and illegal operations.

The China Consumers' Association upheld 3,698 complaints about the private education industry in 2012, a rise of more than 8 percent from 2011.

However, there is no suggestion that any of the schools named in this story have engaged in underhand or illegal practices.

One extreme case illustrates the chaos in the education and training industry. In May, a man drowned while attending a "death-training course". In his quest to conquer a number of unspecified "fears", the man allowed instructors to repeatedly hold his head underwater for varying periods of time, with unforeseen, but fatal, results.

The unfortunate student had paid 30,000 yuan for the three-day course, according to the Southern Daily, which reported that the three "instructors" were secondary school graduates who had no appropriate qualifications, but had already overseen more than 20 similar courses in Guangzhou.

'Cannibalism'

As more small institutions enter the market and struggle to survive, competition is becoming increasingly fierce.

Yu Minhong, founder and CEO of New Oriental Education and Technology Group - one of China's most successful fully accredited educational institutes - referred to the competition as "cannibalism" at the 2013 Summit of the Private Educational Industry.

"This typically Chinese mode of thinking has resulted in the bloody collapse of many training institutes," he said.

Yu used the growing trend for expensive "customized" training courses to illustrate his point. The profitability of this sort of course, where fees are much higher than those for traditional teaching, has seen the number of providers mushroom as newcomers jump on the bandwagon en masse.

The result is that few establishments are able to make a profit and many are forced to close. Sometimes the owners abscond without reimbursing the students.

"The competition is becoming increasingly fierce because there is almost no difference in the products being offered by the various players. The biggest difference is the teachers," said Margaret Yang, a former partner of a training institute in Nanjing, who has worked in the industry for seven years.

She said a lot of training institutes are trying to fight their way out of this "homogeneous" competition, but it's difficult. "The teachers are the most important factor. It usually takes us two years to cultivate an excellent teacher, mostly English graduates from China's top universities."

"Unlike the manufacturing industry, where production can be expanded simply by using more facilities and equipment and employing workers who can improve their skills quickly, the expansion of a training institute requires good talent and careful management," she said.

Venture capital

While an influx of venture capital has fueled this runaway growth, it hasn't necessarily improved the quality of teaching.

In 2004, a venture capitalist, Tiger Management Corp, also known as the "Tiger Fund", entered China's private education industry. Its first investment target was Yu's New Oriental, which in 2006 became the first Chinese education provider to go public overseas when it listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Since 2006, spurred by New Oriental's listing and the high expectations for the Chinese training market, eight organizations, including Ambow Education Holdings and the TAL Education Group, have listed in the United States.

Company statistics show that by May 2012, New Oriental had established 55 schools and more than 600 training centers nationwide and, since the 1990s, it had provided training for 13 million people.

However, during the last fiscal year, New Oriental opened 238 centers, registering quarterly growth of more than 40 percent, a "horrible" rate of expansion, according to Li Ying, a veteran educational industry analyst quoted by South City News. New Oriental predicts that fiscal 2012/13 will see revenue grow by 25 to 30 percent.

That growth has been the source of a number of problems, according to a teacher who insisted on using the pseudonym Zhang Yichi. He has taught a wide range of English courses at New Oriental's Nanjing branch since graduation two years ago.

"I think one of the problems is that the scale is so large that the company needs more teachers, but it can't guarantee the quality of its recruits. Years ago, the level of teaching was higher. Now, some teachers' English language abilities are unacceptable. Their pronunciation, grammar, aural and spoken skills are awful, but they are still allowed to teach vocabulary courses," he said.

Another employee, who declined to give her name, said, "After the listing, the company became so large that I felt only a financial relationship existed between the teachers and the company. There are no corporate values, the teacher-appraisal system is unworkable and the pay and benefits are not good enough. Many of the teachers have left and gone to other institutions."

As Dong Shengzu, dean of the Non-Government Education Research Institute of Shanghai Academy of Educational Sciences, explained: "Venture capital investors are not philanthropists. The quest for profits and the rapid expansion of training institutes will result in the social value of education being overlooked."

The pressure to become profitable has led some operators to engage in illegal activities such as the use of misleading publicity materials, unfair competitive practices and even embezzlement. This has damaged the credibility of private educational and training institutes and harmed the interests of consumers, he said.

Future tense

Caught in a developmental impasse, officials and industrialists expect a major shake-up soon.

"As competition becomes fiercer, the industry reshuffle will accelerate, which will lead to competition for capital, services, talent and hardware among these companies. Small institutions, or those without special products, will go to the wall and blind expansion and vicious competition will be reduced," said Jin Xin, CEO of Xueda Education Group, quoted by China Reform Daily.

Zhang Jiaxiang, chairman of the China Association for Non-Government Education, said, "We hope that the Ministry of Education will soon amend the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Promotion of Privately-run Schools, and provide detailed regulations so the industry can develop healthily and the public can actually enjoy the developments in education."

The law, enacted in September 2003, defines private educational and training organizations as nonprofit legal entities. However, they are not forbidden from earning a "reasonable" income, which makes it difficult for the State Administration of Industry and Commerce and the ministries of education and labor and social security to jointly supervise and regulate the companies' commercial activities.

Earlier this year, after much urging from the Ministry of Education and the China Association of Non-Government Education, 17 education and training institutions, including NYSE-listed companies such as New Oriental and TAL Education Group, signed a joint pledge to standardize qualifications, services, quality, fees, competitive practices and cooperation in the tuition of primary- and middle-school students.

Some training and education providers have also been in talks to explore new services to break the trend of "cannibalism" and return to the traditional ideals of education.

As the need for training diversifies, many companies are exploring business models that focus on specific demographic groups.

First Smart Education's customized tuition services for primary- and middle-school students account for 70 to 80 percent of its business. The targeted customers are from middle class and wealthy families and tuition fees are on average 30 percent higher than those charged by regular institutions.

The company's revenue has grown at an annual rate of between 200 and 300 percent in the five years since it was founded. First Smart attributes this to its educational ideals and its practice of assessing the performance of its teachers via feedback from students. "Our training is a combination of the strengths of Eastern and Western education," said CEO Zhang Xichang, quoted by Southern Metropolis Weekly.

In a speech at the 2013 Summit of the Education and Training Industry, New Oriental's Yu Minhong sought to emphasize the importance of ideals in the modern education industry: "If children attended our classes for just one day, they would definitely understand our influences and benefit from them."

Yu commented that he regretted floating New Oriental in the US, saying that if the listing hadn't happened, "The company would have been better off, overall. Four or five years after we went public, I realized that the survival of the education and training industry is closely connected to its social value and has nothing to do with stock market listings."

Contact the author at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn

|