For the China watcher in us all; the newest analysis of demography and the effects of the maturing crop of One Child Policy Chinese will either mean a boom or boon for the Chinese economy. What might this mean for second tier cities like Tianjin?

The key points of the demography discussion in China are that, according to the US Census Bureau, the Chinese population will ultimately stagnate at 1.4 billion by 2026. Secondly, what this means by extension is that the labor force, China's historic economic advantage, will shrink as the population ages into retirement. The pool of young workers to replace their parents is drying up. More interesting findings of the Census Bureau include the estimate that in 2010 the segment of the population aged 20-24 peaked at 124million. Even if you include the population aged 20-59 (working age) the peak in labor force will come in 2016 at 831 million. This seems like a big number, and it is, but India and Southeast Asia are experiencing population growth which in this situation means cheaper available labor and a population not burdened by a greater proportion of retirees, both sources of heartache for China's economy.

In India, the aged 20-24 segment is not expected to peak until 2024 at 116 million and overall India is expected to be the world's most populous nation by 2025. Thanks to the OCP, China's fertility rate is around 1.6, and India's is 2.7 (fertility rate is the number of children a woman will have in her lifetime and is closely tied to population growth). While the OCP is loosening it may be too little too late. It all depends on the state and composition of the economy at the time of population growth stagnation.

China is not the first country to weather major age demographic shifts, so looking to other economies, and importantly the state of their economies at the time of stagnation may help predict what will happen in the Middle Kingdom as its population ages, and the OCP tries to adjust accordingly.

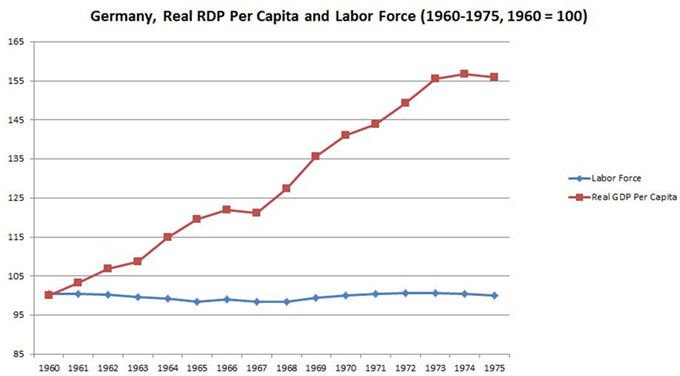

Germany saw a similar population stagnation in the 1960's to 1970's and even shrank thereafter. According to Mark Adomanis at Forbes.com, Germany's GDP per capita counter intuitively boomed during the same period of population stagnation.

If that was the case China should be rejoicing in the potential of the OCP to eventually boost GDP per capita, and thereby ushering in a higher standard of living never before seen in modern China. But obviously the German economy of 1960 is not parallel to China's economy today. In fact in 1960 in Germany the per capita income was already many times what China's is, and will be, in the near future. Adomanis also points out that Germany's growth "…was not simply the "catch-up" growth that has been China's stock in trade for the past 30 years". Put another way, China and Germany will be at different stages of development when their respective periods of population growth stagnation hit.

It may be more helpful to compare an Asian neighbor with more economic and demographic parallels to accurately read the tea leaves on China's future. Not that China would necessarily like to be compared with Japan, but there are parallels between China today and the boom in Japan from 1950 to 1970 and the subsequent decades long decline in Japan that China wants to avoid.

Brian Reading and Diana Choyleva of Lombard Street Research point out in a recent report that private savings rates are/were high in both countries leading to banks being able to loan out a large amounts of capital to the industrial sector. This is partially due to a tightly controlled financial sector and in China's case a serious lack of alternative places to stash cash (besides real estate which creates its own problems). In both countries, economic growth relies on export demand, which is propped up by an undervalued currency, the yen and yuan respectively. Add to this the crony capitalism of China and the cross-shareholding in Japan that makes for deep rooted special interest in maintain the economic status quo and you may have a better indicator of China's fate than what Germany offers. One last and very important point from Reading and Choyleva,

… Japan's business and government sector invested to excess in its boom, resulting in a misallocation of resources which, ultimately, turned into a significant drag on growth as banks were encumbered by bad loans. …China's gross capital investment levels in recent decades have actually been even higher. While Japan invested up to 36 per cent of its GDP in its fast growth phase, China has lately been investing close to 50 per cent.

Is all that investment really sustainable? If the investment is coming from debt, what might the results be? Some Chinese cities are already seeing city government debt far outpacing revenues and there has even been talk of the national government having to set up a fund to bail out municipal governments that have overspent on superfluous projects, many times in the name of city branding over meaningful infrastructure, I'm looking at you Tianjin Cultural Center.

So is China doomed to the slowing growth of Japan due to structural and demographic crisis? Not necessarily. If the government can deliver on the promises of reform in the financial and other sectors, and address the problem of an economy that relies on exports and cheap labor that will all too soon not be cheap, China can avoid economic stagnation in the face of population stagnation. Second tier cities, like Tianjin could be more negatively affected by shrinking labor pools.

Tianjin already suffers from a brain drain. The city is known nationwide for its excellent secondary and post-secondary education but despite this, the talent leaves after graduation in search of opportunities in other cities, or countries. This problem would likely become exacerbated when the labor pool shrinks and the brain drain quickens pace.

I believe it is fair to say that while often creating hardship and interference at the household level, the OCP will soon have even greater impact on the macro-economy. But the policy is seeing reforms, slowly but surely; those born under the OCP regime are now allowed to have a second child four years after their first child if their spouse was also born after the implementation of the policy. Even in a perfectly nimble and impartial system, meeting the challenges of the labor pool bust brought on by the OCP would be exceedingly difficult, though not impossible. However, we live in China and like any country its particular idiosyncrasies and conservatism may complicate reform in regards to these challenges. However, with the right management the economy could become more dynamic, more consumer friendly, and less difficult for foreign firms to do business and partner with China to avoid the looming OCP labor bubble. The next thirty years of reform and progress may not be as bright as the last thirty, but they need not be the doom and gloom that some analysts see. It all depends on you level of optimism, and as I am learning this seems to be inversely related to one's length of time in China. Here's hoping the new reforms of the OCP meet China's demographic challenges today, and tomorrow.