Towns of a kindred spirit

Moutai, a premium liquor that's a symbol of China, sees its own quality standards as well as tourism to the town where it's made and incipient overseas sales as reasons for optimism

The town is carved into the stony face of the mountainside, homes and businesses and crops clinging in clusters on tiny manmade plateaus. By gradients and layers, the bustle of everyday life spills down the slope on twisting streets and hairpin turns, finishing just short of where the Chishui River flows between banks of red clay. The river runs slow here, as if conserving its strength to finish the last leg of a 500 kilometer journey out of Guizhou province and into Sichuan.

Hu Jingshi, 63, says there is something special about the water in this place where river and mountain meet. Since the time of emperors, the locals have used it in homemade stills that sprout like wild mushrooms on roofs and roadsides up and down the slopes.

|

Workers on the packaging lines put the finishing touches on the iconic brand's bottles. Photos by Wang Zhuangfei / China Daily |

|

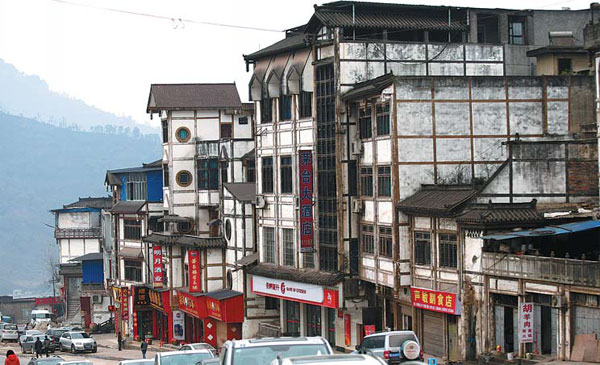

Farmland in Tanchang, a neighboring town of Maotai. |

|

Maotai town, where the nation's most famous spirit is made and bottled. Photos by Wang Dazhuang / China Daily |

The distinctive liquor they produce, called baijiu, or white spirits, is the lifeblood of this little place called Maotai town.

And its beating heart is the Moutai distillery, where the nation's most famous, popular and expensive alcoholic spirit is made and bottled.

Although baijiu is relatively little known and infrequently consumed outside of China, all that may be about to change, and this secluded township in China's southwest is the command center for a push that if successful would see Moutai become a big brand in the European market.

"Chinese love Moutai, because we love China, and Moutai represents China," says Hu, who began working at the distillery in the 1970s.

Now retired, he volunteers as the company's amateur historian, spending his days cataloguing and organizing a computer full of scanned sepia photos and yellowed documents from Moutai's storied history.

His digital archive shows how the brand's rise has been intrinsically linked to that of modern China.

The Red Army, rag tag and on the run, treated its wounded with the town's famed liquor when it passed through in 1935 on the Long March. In the early 1950s, not long after a merger of the three largest distilleries in town formalized the modern day Moutai brand, it was proclaimed China's national spirit. It was used to toast the beginning of diplomatic relations between the United States and China in 1972, and the British handover of Hong Kong in 1997.

Now wholesaling at about 819 yuan ($131; 114 euros) for 500 milliliters of the basic five-year-old drop, but often selling upwards of $50,000 for older vintages, in more recent times it has been the chosen beverage of China's elite.

But just as Moutai and the surrounding town have mirrored China's peaks to date, they also seem vulnerable to its troughs.

China's slowing economy, and recent measures that were introduced to limit spending and gift-giving among government officials, have been felt at Moutai company and have hit residents in the hip pocket all across the town.

More than just a national symbol, Hu says Moutai and Maotai town are in essence a weathervane for China.

In his shop on Baijiu Street, the town's main retail thoroughfare, Deng Xi picks up one of the bottles lining the walls and hefts it.

"We make this baijiu ourselves down on the other side of the river from here," he says. "It's a family business, passed down for generations."

His wife and two young children eat sunflower seeds at a wooden table up near the back wall. Otherwise the shop is empty, and Deng says this has all too often been the case recently.

The 31-year-old believes business has slowed for small-time producers like him since the government's austerity measures were introduced in 2013, a move aimed to cut down on spending and crack down on corruption.

"The sales volume has been affected," he says. "It's going down and it's not as good as before. Our sales volume is about 3 to 4 million yuan per year. In the past, though, it was as much as 5 to 6 million yuan per year."

While his family's liquor doesn't have the same prestige as the Moutai brand, Deng says the fact that they make their baijiu in Maotai town with the fabled water of the Chishui is enough to allow him to command about 800 yuan for a 500ml bottle. The only problem is, less people seem able or willing to buy.

Literally at the top end of the town, the flattened summit of the mountain has been turned into a lookout that is ringed by homes and small plots of crops and wandering goats. The local Party deputy secretary chief, Zhang Jiebo, gestures broadly at a swathe of land by the banks of the river spread out far below.

"Over there is where Moutai is expanding," he says.

But the frenetic pace of work usually seen in China is missing here. Moutai management is hazy on when the work (which is touted to double production capacity and would include a five star hotel for tourists) would get going in earnest, although they think the original 2020 completion date will still be met.

Zhang says the entire town is being upgraded for tourism. Down on the waterfront, a giant hotel is taking shape. Narrow roads are being widened. Trees and bike paths are going in.

"You can see there are a lot of construction projects - 23.5 million yuan has been invested in 64 projects and 24 are currently underway," he says.

About 10 percent of China's baijiu is produced in Maotai township, including the famed Moutai brand. Zhang says it's a big draw card and last year brought in about 2 million visitors who added 44.7 million yuan to the local economy, a 20 percent increase from 2013.

Liu Ningrui, another local official, says 70-80 percent of the population's income is derived directly or indirectly from the baijiu industry.

At around 20,000 yuan, the annual average per capita income for Maotai residents is much higher than the 6,300 yuan per capita average for the whole of Guizhou province. But the town's balance sheet reveals things are slowing down.

"GDP growth is slowing down," Liu says. "It used to grow at 17 percent. Now we are expecting a more steady and lower percentage of 12-13 percent growth."

Moutai maintains its brand is largely insulated from recent market fluctuations.

In 2013, Moutai's sales revenue reached 40 billion yuan, a 13 percent increase from 2012. At the moment, the company sells about 17,000 tons of product per year, with the remaining 23,000 tons produced annually cellared and aged for future sale.

By comparison, in 2013 French luxury cognac brand Rmy Martin and its parent company Rmy Cointreau saw its profits decline by 46.9 percent, according to international spirits industry magazine The Spirits Business.

Sales of the top selling brandy in the world, McDowell's No 1 Brandy, dropped by 15 percent in the same year, and sales of Moet-Hennessy's flagship Hennessy Cognac only grew by 1 percent.

A slump in sales in China is largely blamed for the falling profits of luxury spirit brands elsewhere in the world, but Moutai seems to have dodged the bullet, or at least managed to get off with only a flesh wound.

The clink of thousands of bottles and the drone of conveyor belts fill the cavernous hangar-like space where one of the packaging lines at the Moutai facility is roaring along. The distinctive fragrance of the liquor, reminiscent of soy sauce, permeates the air as hundreds of white-clad women slap labels, lids and boxes on each bottle.

The section manager, Li Shuai, looks down on the hive of activity from a walkway above.

"This is one of 12 lines, although some of them make some of our different brands," he says. "We can do up to 32,000 bottles, or 15 metric tons, in a day on this line. We can make 70 to 80 tons per day across all lines."

Each of the women, like most workers at the plant, does about a six-hour shift per day, five days a week. The average wage is about 100,000 yuan per year, more than the average starting salary for a university graduate in Beijing.

Li raises his voice to be heard above the din. "Packaging is now on demand," he says. It used to be as much as we could do in a day."

One of the packaging team group leaders, 26-year-old Wang Zhihang, says she's noticed a subtle shift in the tempo on the line.

"I can feel it (is a bit slower)," she says. "Everything has ups and downs, but I am confident about the future of my career here."

Wang, who started as a basic worker on the line three years ago, now makes more than both of her parents do as teachers.

There's genuine pride in her voice when she talks about her job. "Moutai is the national drink," she says simply by way of explanation.

That the spirit is a national icon, and is treated as such, is indisputable. In the past few years, about 1.5 million people have been relocated from their homes on the banks of the Chishui after water contamination fears were raised in 2009. Such is the determination to protect Moutai.

On a workshop floor that steams and hisses like a volcanic field, barefooted men shovel a mixture of sorghum and wheat into fermentation chambers, a stage in processing some of the major ingredients for the spirit-cum-national symbol.

The company's mantra is that Moutai is the essence of China, packaged up and distilled in a bottle. The workers at the distillery, and the farmers that supply raw ingredients, certainly embody many of the hallmark characteristics of the modern nation. Family, tradition, modernization and social mobility can be seen in the lives of those adding ingredients to the literal, and metaphorical, spirit of China.

Wang Hongqiang, 40, is one of three generations in his family that has worked at the distillery.

"My father, my son and my wife and myself all work, or have worked, here," he says. "Moutai has given me a lot. My whole life, everything is Moutai."

Outside of town, where small farming villages cluster between terraces of verdant green crops, Tong Hu is preparing to slaughter a pig for the Spring Festival feast. Tong, 55, began growing sorghum to sell to Moutai in 2006.

"Life is getting better," says Tong, born to poor farmers who grew corn, in a household where there was never enough to eat. He makes about 20,000 yuan a year farming 1 hectare of land. His son works for Moutai, and his two daughters are studying to work in medicine and finance. "Sorghum gave us the ability to support three children through college," he says.

The fact that Moutai is so distinctive in taste, and so uniquely tied to Chinese culture and national identity, is also the reason why many pundits think it's going to be a hard sell overseas.

Wang Jiangyue, who works in the company's new Paris office, says Moutai has made inroads in France, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom and Switzerland. But she agrees the spirit is not going to be an overnight success in the European market.

"At the beginning, it is not always so easy," she says. "Some European countries, especially like France, already are countries of red wine and cognac, so people are rather proud of their own alcohol. So each time when we present Moutai to a European, we have to be patient, and once he or she has a taste of our product, then (they) will be conquered directly by the taste. As we always say, Moutai liquor itself is the best marketing campaign."

That said, the company has launched a more traditional marketing campaign, and has formed promotional partnerships with Partouche Casinos and five-star hotel chains in France like Intercontinental, Shangri-La and Peninsula Paris.

Wu Dewong, the company's strategic manager, concedes the majority of overseas buyers are Chinese or people who have Chinese roots.

In 2014, the company sold about 3 percent of its product abroad, netting about $200 million, a 20 percent increase in overseas sales since 2013.

"Other brands went down, but we are going up," Wu says. "Moutai is the trademark of China. But to be a global brand, we need to be making 20 percent of our sales overseas."

In his office near the river, historian Hu says his wage was 18 yuan a month when he started with the company in the 1970s. The work was hard and conditions were harsh. In his lifetime, he's seen the grunt work mechanized and the pay grow dramatically. He's witnessed China develop at breakneck speed, and he's seen Moutai's status as a national icon grow with it. All this gives him confidence about the future for Moutai, and the little town that relies so heavily on it.

"As long as China is thriving, Moutai will be thriving," he says.

josephcatanzaro@chinadaily.com.cn