A vocational school teaches the essentials of a start-up

Updated: 2012-08-12 07:52

By Hannah Seligson(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

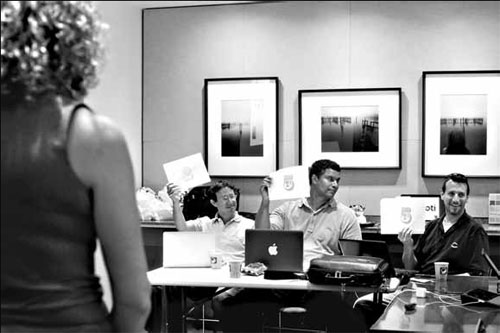

At the Chicago branch of the Founder Institute, one of the organization's 27 chapters in 14 countries, mentors reacted to a student's start-up idea. Sally Ryan for The New York Times |

Can you build a technology entrepreneur from scratch in four months flat?

Yes, contends a global training program called the Founder Institute, which was started in 2009. For tuition of less than $1,000, students attend classes with one goal in mind: to create a fully operational company. In fact, they are required to incorporate before they graduate.

To be accepted, students don't need to have a fully baked idea, but they must take a test that the institute says can predict their entrepreneurial success. They can keep their day jobs, but the workload is grueling, and 60 percent of the students fail to graduate.

But this for-profit institute, based in Mountain View, California, says it has helped start more than 500 companies. It has done so by going global, with chapters in 14 countries, in 27 cities. It aims to make money partly through its equity stakes in the companies created by its graduates.

Boaz Fletcher, 44, a consultant to new companies in Israel, started the Tel Aviv branch this year. "As a country, Israel is amazing at technology, but not great at building sustainable businesses, and that is one of the things the Founder Institute teaches: how to build an enduring, stable company," he said.

The institute is the brainchild of Adeo Ressi, 40, who has started eight companies of his own. Back in the mid-1990s, he was a co-founder of Total New York, an online regional city guide that was acquired by AOL.

Mr. Ressi saw a need for nurturing entrepreneurs even before the idea stage. He set out to create a vocational school of sorts to teach the nuts and bolts of entrepreneurship.

As C.E.O. of TheFunded.com, a Web site where entrepreneurs and chief executives rate venture capital firms and investors, he has a community of founders at his fingertips, and he was able to ask them: What would they have done differently at the beginning?

The curriculum is partly based on answers to that question from 2,000 executives. Classes often consist of around 30 students, and in 15 sessions they learn about revenue, costs and profits; marketing and sales; presentation and publicity; and fund-raising.

Sessions are taught by seasoned entrepreneurs who can also serve as mentors. Fundamental to the institute is the belief that many aspects of entrepreneurship can be taught. Jose Luis Senent, 43, had been a car broker in Paris for 20 years. He graduated from the Paris chapter in April 2011 and now runs Autoreduc, a group-buying site for cars that he says is profitable and will expand into Spain, Belgium and Switzerland this year.

"I cannot imagine starting a company without knowing what I learned at the institute - there is so much to know about marketing, business models and raising money," Mr. Senent said.

Mr. Ressi says he wants to help budding founders avoid rookie mistakes - like bad Web design and off-key marketing.

Katherine Bicknell, 31, a graduate of the New York chapter and co-founder of Kindara, an app that helps women track their fertility, would still be calling her company "Moonlyght" if not for a session on naming and branding.

"The Founder Institute said that you had to be able to say it, spell it, read it easily and the dot-com had to be available," said Ms. Bicknell.

By opening up networks and opportunities to those on the outside of the tight-knit start-up world, the institute aims to democratize the access that up-and-coming entrepreneurs need.

It "helped me build my network - when I came from Turkey to the U.S. in 2008 to start my company, I didn't know anyone," said Eren Bali, 28, co-founder of Udemy, an online learning company that has raised $4 million from investors.

Carlos Rozo, 38, a graduate of the chapter in Bogota, Colombia, said the institute steered him away from a potentially fatal mistake - starting something big and complicated - and toward something more narrow that would fill a niche. He abandoned plans for a content-sharing platform in favor of Thotz.net, a provider of software that companies can use to share information among employees.

Tuan Pham, 37, began the Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City sections in Vietnam in 2011.

"The fact that the Founder Institute agreed to work with us is huge - otherwise, we would have to rely on what we read from books," said Mr. Pham, founder of the Topica Education Group, a Hanoi-based online learning company with 300 employees.

Graduates put 3.5 percent of their company into a shared equity pool. If a company is sold or merged or goes public in 10 years, 30 percent goes to the mentors, 30 percent to the entrepreneur's graduating class, 25 percent to the local chapter leadership and 15 percent to the Founder Institute.

The institute says that 42 percent of participants have received external funding in their first six months of operation and that about 10 percent of its companies have failed. The Founder Institute attracts somewhat older entrepreneurs who have day jobs; their average age is 34.

Some experts are skeptical, however, about an after-hours entrepreneurship model. "We like to fund people who are working on their ideas full time and are world experts," said Aziz Gilani, a director at DFJ Mercury, a venture capital firm based in Houston.

The Founder Institute also helps some people see they may not be in the right position to run a high-growth start-up. Phil Libin, a mentor at the institute and founder and C.E.O. of Evernote, the online software program, says: "I ask people, 'If I could guarantee that you would spend the next 10 years developing a product millions of people will use but you will make no money for a decade and it will be a total financial failure, will you do it?' Most people answer no. Some people drop out of the program because of the question."

The New York Times

(China Daily 08/12/2012 page10)